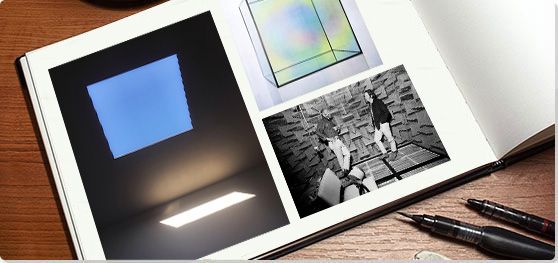

Summary of Light and Space

Ethereal and atmospheric, yet often equally geometric and analytic, the experiences of the Light and Space movement present a striking paradox to the viewer, one that requires active, and often multi-sensory, participation. There is no single defining aesthetic amongst the loosely affiliated group of Los Angeles-based Light and Space artists, but instead a preoccupation with the viewer's perception and participation. Their work ranges from site-specific installations washed in radiant, neon light, or even projecting from the wall, to mysterious glowing columns placed within a darkened room, to totemic sculptures made of glass, acrylic or resin, which reflect and absorb ambient light and shadows, instead of radiating their own.

The genesis of the movement occurred in the late 1950s and lasted through the 1970s, with a wide array of artists following similar conceptual philosophies, including Peter Alexander, Larry Bell, Craig Kauffman, Mary Corse, Frederick Eversley, Helen Pashgian, De Wain Valentine, and perhaps the best-known Robert Irwin and James Turrell. The group found inspiration in idyllic popular notions associated with Southern California: sun, cars, surf, and sand. Yet, in equal measure, there is an embrace of psychology and technology that unite these artists in explorations of materiality and human perception throughout their distinct bodies of work.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Light and Space developed in parallel to the dominant Minimalist movement in New York in the early 1960s, each characterized by industrial materials and a hard-edge, geometric aesthetic. However, where seriality and repetition was a key component of Minimalist works, artists associated with Light and Space usually created singular objects, whether sculptural or environmental in scale.

- One of the signature characteristics of the Light and Space movement is the choice of alternative materials employed in the creation of both two- and three-dimensional works of art. In lieu of paint and canvas, or marble and bronze, these artists looked to alternative materials as seemingly mundane as glass and plastic as well as experimenting with newer technologies, particularly polyester resins, cast acrylic, neon and argon lights, influenced by the flourishing aerospace industry.

- The term "Light and Space" derives from a 1971 exhibition at the UCLA University Art Gallery, titled Transparency, Reflection, Light, Space: Four Artists, including Peter Alexander, Larry Bell, Robert Irwin and Craig Kauffman, in which, as described by the catalogue, "the works displayed served as liaison between the artists and the spaces they chose to animate." Through this idea, the connection of Light and Space to Kinetic Art is revealed, as it is the experience, over the object, which the artists emphasized.

- The movement has also been called California Minimalism, because, as art critic Sascha Crasnow wrote, it is similarly defined by Minimalism's "qualities of stripping down the object... but added in a uniquely Californian spin - the interaction of light and space." The movement is also closely related to Finish/Fetish, a term first coined by John Coplans in the late 1960s referencing a trend toward the use of plastics with glossy finishes and highly polished surfaces, perhaps best exemplified by artists Billy Al Bengston, Craig Kauffman, and John McCracken.

- The concept of The Sublime resonates within the all-encompassing aesthetic experience of a Light and Space installation. Feelings of timelessness permeate the multisensory event, overwhelming and nearly transcendental, evoking the definition offered by German philosopher Emmanuel Kant who describes the sublime as "found in a formless object insofar as limitlessness is represented in it." Therefore, the sublimity of the Light and Space experience does not reside in the physical object or even the space where the work is situated, but in the ethereal phenomenon of light itself.

Overview of Light and Space

Artist Robert Irwin refused to allow any of his works to be photographed because he felt that the experience of his work could not be fully captured in print. This exemplifies the essence of the movement; Light and Space artists used cutting edge mediums to create ephemeral visions and optical illusions that captivated. Works that were dismissed in the press as “Californian - of no significance at al” went on to see critical acclaim and have an enduring influence to this today.

Artworks and Artists of Light and Space

Untitled

Irwin's Untitled installation takes over an entire wall. It is an elusive work consisting of a singular painted concave aluminum disc, five feet in diameter, placed twenty inches out from the back wall and lit from multiple sources of light. Despite the mundane list of materials, the disc appears to nearly dematerialize and hover in space. The edge of the disc is hard to define visually as it forms fluidly out of the interplay of light and shadow, and the defined edges of the concrete object disappear. This photograph captures a single ephemeral moment in a continual interaction of light and space, and, aware of this, in the 1970s Irwin refused to allow any of his works to be photographed because he felt that the experience of his work could not be captured in the medium. As art historian and curator Evelyn Hankins noted, his works "because of their extremely subtle nature, demand in-person viewing," and that "Irwin's art becomes fully present only when you are standing in the physical space, experiencing it over a period of time."

Although fixed in space, the sculptural object appears ephemeral. The experience is not just about the illusion, but the participation of the viewer and an awareness of their own perception, which part is object and which part effect, while trying to 'fix' the shape within visual focus. As art historian Kirsi Peltomäki notes, Irwin's work "from 1962 onward explored deploying minimal visual means to activate the viewers' perceptual process and redirect their attention self-reflectively to their own processes of seeing."

Acrylic paint on shaped aluminum - Hirshhorn and Museum Collection, Smithsonian Institute, Washington DC

The Absolutely Naked Fragrance

The transformation of a simple piece of plywood into an aesthetic object represents a trademark series of Los Angeles artist John McCracken. Treated with fiberglass and resin, the resulting finish is a highly reflective and glossy surface with a sensuous visual appeal, while the diagonal created by the leaning rectangular form creates a spatial interaction between the floor and wall. In 1966, influenced by the color field work of Barnett Newman, the artist began making what he termed his "planks," as if the "zips" of Newman's monumental works emerged from the painted surface into the space of the viewer. As the artist said, "I see the plank as existing between two worlds, the floor representing the physical world of standing objects, trees, cars, buildings, human bodies, and everything, and the wall representing the world of the imagination, illusionistic painting space, human mental space, and all that."

While the meticulous surface and illusory reflections therein bear striking resemblance to the works associated with the Light and Space artists, these "planks" represent the essence of the closely related Finish/Fetish movement, which also began in the 1960s beach culture of Southern California. The luscious candy-wrapper colors of McCracken's monochromatic planks were inspired by Southern California's car culture, evoking the cars that he saw as "mobile color chips." The work plays upon the viewer's shifting perception, as the sculptor's hand-finished surfaces evoke painterly notions, and as art critic Roberta Smith wrote, "the leaning pieces were so casual as to seem like jokes, except that their intense hues and flawless surfaces projected dignity and beauty; they often seemed to be made of solid color, but also had a totemic presence." At the time, some attributed the shape to the monolith of Stanley Kubrick's groundbreaking 2001: A Space Odyssey as McCracken's influence. The artist believed in time travel and extraterrestrials and said, "Even before I did concerted studies of U.F.O.s, it helped me maintain my focus to think I was trying to do the kind of work that could have been brought here by a U.F.O."

Plywood covered with fiberglass and resin - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Untitled

While many of the Light and Space creations were monumental in size, Pashian often worked on an intimate scale, as seen in this translucent sphere, only seven inches in diameter. This remarkable object seems to alternate between translucence and opacity, with exquisite and ever-shifting variations of light, the result of its highly polished surface. As the sphere is illuminated, the vertical acrylic rod at its center, creates varying optical effects depending on the illumination - in this particular photograph suggesting an organic enfolding or a door into the object's space. Yet, as the artist noted, here "light is the object," and as the viewer perceives the sphere from different vantage points, the embodied light beckons with a mysterious vitality, while remaining indeterminate. As James Turrell said of Pashgian's work, she "bridges the material and the immaterial, the visible and invisible."

Born and raised in Pasadena, the artist began her career as an art historian, studying the Dutch Golden Age and the works of Vermeer in Boston. While working towards a Ph.D. at Harvard University, she returned to art making and soon thereafter to Southern California. In the 1960s, she began to work in cast resin creating small geometric sculptures, usually discs or spheres such as this, ranging in color from clear to vibrant primary hues. The effect of the work depended upon a meticulous surface, as the artist noted, "if there is a scratch on the surface, that's all you see." As the traces of artistic processes are erased, the work appears to be an almost elemental form, which as art critic Lita Barrie relates to the German philosopher Immanuel Kant's transcendental aesthetic of the sublime, "limitless and unknowable; we can only imagine in glimmers, but it fills us with awe, the same awesomeness we experience in the grandeur of nature."

When these works were exhibited in New York in 1971, they, as well as the concurrent exhibits of Robert Irwin and Laddie John Dill, were dismissed by a newspaper critic "as Californian - as of no significance at all." In the following decade, as the male members of the Light and Space movement began to receive critical acclaim, Pashgian was often overlooked. However, since the 2010 Pomona College Museum survey of her work, her career has been revitalized. In 2014, a major installation at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Helen Pashgian: Light Invisible, mesmerized both critics and the viewing public.

Cast sphere, clear polyester resin with insert of clear acrylic rod - Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, California

Untitled (Light Painting, Grid)

The composition of this white painting contains a subtle grid, its faint lines, as if cast by shadows and light, receding and advancing into view. The acrylic surface, embedded with glass microspheres, varies in reflectivity, sense of depth and color. The appearance of Corse's work changes as the light and the viewer's point of view change, an effect that can only be experienced by an encounter with the artwork itself (in line with Robert Irwin's refusal to let his artwork be photographed). Corse's work similarly demands intimate encounter, requiring that the light be experienced, rather than simply "seen."

As art writer Catherine G. Wagley wrote, "her white on white paintings ... create a trippy experience. Made with the microspheres, they look different from every angle." As Corse put it, "The painting is not really on the wall, it's in your perception. It also brings in time - the time to walk along the whole thing. They forgot it should be Light and Space and Time."

Beginning as an Abstract Expressionist, Corse began making white fluorescent light boxes in 1966 while studying at the Chouinard Art Institute. By 1968, she was studying physics and developing light boxes that used argon gas, the light powered by Tesla coils, saying it was "the vibration of light" that interested her. She also began experimenting with glass microspheres, inspired by lit up highway markings made with the industrial product, and mixing them with acrylic paint to create the white shimmering paintings, for which she is still best known. While also creating installations and environments, she never abandoned painting. Instead, it is her paintings which transform the setting over the room forcing the viewer's movement and active participation in order to activate the surface.

Glass microspheres and acrylic on canvas - Portland Art Museum, Portland, Oregon

Untitled (Parabolic Lens)

This polyester disc, its highly polished surface radiating with translucent color, resembles not only the parabolic lens of its title but an otherworldly object that is simultaneously intimate, like a living mirror. The shape is flat on the back and concave on the front, where the resin thins to saturated blue, evoking the retina of the human eye or an image of the sky refracted upon it. The parabolic form became iconic to Eversley's work, as he explains, "The parabola happens to be the only mathematic shape that concentrates all forms of known energy to the same single focal point."

Trained as an engineer in Pittsburgh at the Carnegie Institute of Technology, Eversley moved to Venice Beach, California in 1964 where he worked for Wyle Laboratories designing projects for NASA and the French atomic energy commission. Venice, as he said, "was the only beachfront community I was able to rent in. It was the only integrated beach community." The move proved serendipitous, as he soon befriended the likes of Bell, Turrell, Irwin, McCracken, and others, using his expertise to assist them on technical issues with artistic projects. He soon began creating his own art, and, after a life-threatening car accident in 1967, left engineering to pursue art full time.

The natural seascape of Venice also informed his work, as he said, "The beach is all about energy. It's the wind, the rain, the sun, the waves. You're surrounded by the presence of energy. You're also surrounded by everyone who comes to the beach, which ends up being - with very few exceptions - in a very positive, energetic state." Eversley is best-known for his parabolic shapes, which he created through his own invention of using a tube, filled with resin, and spun on a horizontal axis. The creation of his meticulous objects was a vigorous, physical process. Eversley said 99 per cent of the work was in the hand polishing, as the molded resin began the process with a rough and dull finish. As art critic Kristen Swenson wrote, "his meticulously polished forms were in dialogue with those by [Finish/Fetish] figures with whom he worked and exhibited, such as Larry Bell and John McCracken, though his concerns are more deeply rooted in the physics and metaphysics of light."

Eversley had his first solo exhibition at the Whitney in 1970 and was the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum's first artist in residence in 1977. His work continues to be acclaimed, as he was awarded the "Lorenzo de' Medici" prize for sculpture at the 2001 Biennale Internazionale dell' Arte Contemporanea in Florence, Italy.

Three-color, three-layer cast polyester - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

RM 669

The glowing blue outline of a square, formed with cool-white neon light, has a hypnotic pull on the viewer. The aura of light creates a shimmering reflection on the floor, which at times seems to exist below, rather than in front of, the wall mounted sculptural form. The viewer's perception of space is challenged as the artist has purposely curved the typically 90-degree angles between the wall, floor and ceiling, and painted them white, to remove customary spatial reference points. Therefore, the neon light, the sole light source in the room, reflects and colors, or "paints," the room in the soft blue light. The walls appear to recede as the viewer moves toward the wall, and the form of the neon square, its diffused light casting no edges or shadows, seems always on the verge of dematerializing. One can almost imagine the interior space of the square as a portal to another dimension.

Typical of the Light and Space artists, the work's emphasis is the experience of perception, rather than the object itself. By altering the entirety of the space it inhabits, the artwork was an early example of the immersive environments pioneered by Wheeler and other Light and Space artists. In a 1968 interview with Time magazine, Wheeler explained, "I want the spectator to stand in the middle of the room and look at the painting and feel that if you walked into it, you'd be in another world." Wheeler began his career while studying painting at the Chouinard Art Institute in the early 1960s in Los Angeles, before turning to a new medium that explored how light could transform and create space. As art critic and curator John Coplans wrote, his "primary aim...is to reshape or change the spectator's perception of the seen world. In short, [his] medium is not light or new materials or technology, but perception."

Vacuum-formed Plexiglas and white UV neon light - Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, California

Diamond Column

This unusually shaped column stands about seven-and-a-half feet tall and nearly four-feet wide, creating a visceral engagement with the viewer. The artist's use of colored and transparent resins creates an illusion of a column within a column. The monolithic sculpture appears illuminated from within, subtly shifting according to the viewer's relationship and the angle of light. The artist said he wanted "to cut out large chunks of ocean or sky and say: 'Here it is,'" and the green column like a chunk of green ocean water visually ebbs and flows, appearing at moments to be almost translucent then darkening to opaque densities. While the hand-finished and highly polished surface evokes a machine-made object, art critic Randy Kennedy has described the artist's sculptures as, "quasi-religious incarnations of coastal light and air."

Valentine grew up in Fort Collins, Colorado but was affected by many of the same influences of his Los Angeles counterparts. He recalls experimenting with painting and welding in his parent's auto-body shop, aligning him with the Finish/Fetish infatuation with car culture. His own family history, which included mining and a gold-prospecting great grandfather, led to an interest in mining, not in practice but visual effect: the young artist was intrigued by the refractive light and brilliant colors of minerals and the picturesque, but highly toxic, mining tailings. But it was true serendipity, as Meredith Mendelsohn explains in a 2015 article for Architectural Digest that secured his fate: "a local defense contractor gave the shop department at Valentine's junior high a batch of leftover polyester resin used for making patrol torpedo boats, and Valentine was hooked."

In 1965, after reading in Artforum on the work of artists Larry Bell, Ken Price, and Craig Kauffman, Valentine moved to Los Angeles where his desire to work in plastic turned toward industrial polyester resins. At the time, commercially available resin allowed for only smaller sculptures, as anything larger would crack in the curing process. Spurred by a desire to create larger work, Valentine invented his own polyester resin that made it possible, such as the Diamond Column, which he created in a single pour. Marketed as Valentine MasKast Resin® in 1970, the product transformed the potential of the medium. The artist created monumental slabs, giant circles, and several 'diamond columns.' The use of the word 'diamond' indicated their shape - highly polished surfaces and faceted light effects - but was also, perhaps the artist's pointed reply to his early rejection by New York City galleries. As Valentine related, they "would look at my slides and say: 'Oh my, that's lovely! What is it made out of?' And I'd say, 'Plastic,' and that was that. It wasn't something one made art out of apparently."

Polyester resin - Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, California

Untitled

This later example of Bell's cube consists of glass panels that appear as if painted or frosted with oval shapes in variations of green, brown, and blue. An oxidized metal frame holds the planes of glass and seems to both contain and extend the tonal variations found therein. Surprisingly, there are no actual pigments that create the 'painted' effect of layered shapes, but the forms are created by light absorbed and reflected by the glass itself. As the viewer walks around the object, colors change and the patterns appear illusory, even the clear Plexiglas plinth seems to dissolve. To create these ephemeral color effects, Bell uses a vacuum chamber to chemically coat the glass panels that, working in effect like a photographic light filter, cut off some bands of light on the color spectrum. The elemental and minimal geometric shapes convey both a stoic solidity, a sense of volume and act as a metaphor for the universe, itself on the same 45-degree plane as Bell's elliptical forms. As the artist has succinctly stated, the "symmetrical shape ... seems to satisfy all my needs for a structural format to hang my ideas on". As art historian Kirsi Peltomäki wrote, "Bell's glass cubes ... reoriented the viewer's reflection into their perception of the material forms themselves."

In 1957 Bell began taking art classes with Robert Irwin at the Chouinard Art School, and, influenced by Irwin's theory of Perceptualism, began incorporating glass fragments into his paintings in 1959. In Bell's words, glass has "three qualities that were really sensuous to me: It transmitted, reflected, and absorbed light all at the same time. Nobody was working with it, it was available anywhere, and it lasted a long time - which is also something I was supposed to do." Bell began making his innovative glass cubes in the early 1960s using a process of vacuum deposition to chemically coat the glass. The earliest cubes employed patterned and colored effects, but by the end of the decade he concentrated on plain glass, treated with quartz and chromium films. His primary focus was to employ cubic volumes as a means for exploring the interactions of light and surface. Art critic Michael Compton has described Bell's work as operating "near the lowest thresholds of visual discrimination. The effect of this is...to cause one to make a considerable effort to discern and so to become conscious of the process of seeing."

Glass and chrome-plated brass - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Meeting

A large rectangular room, white walls lined with large teak wood benches with backs higher than most viewers standing height, provides an early example of James Turrell's Skyspace works. It appears ordinary enough, albeit rather stoic upon first entry, except for what is missing. Immediately apparent, a significant portion of the ceiling and roof of the structure has been removed by the artist, thus revealing an unobstructed view of the sky. The Baroque infatuation with di sotto in su (literally meaning "looking up from under"), to create trompe l'oeil illusions of the sky (found in many European churches), has been replaced, quite literally, with a view of the real thing.

The view from this room, however, is not an unmediated experience. Hidden within the architecture of the room, multicolored LED lights placed along the top edge of the teak bench, are computer programmed to synchronize with sunrise and sunset, to slowly cycle through a series of saturated hues that interact with the light from outside. The time-based performance combines the natural and man-made, transforming not only the glowing colors of the walls but the sense of spatial and structural solidity. The overall effect is to create an interior private space for an elemental encounter with color and light, while the title "Meeting" evokes the meeting house with its shared experience of transcendence, perhaps a nod to Turrell's Quaker background. Art critic Jori Finkel has described the space as a "celestial viewing room designed to create the rather magical illusion that the sky is within reach - stretched like a canvas across an opening in the ceiling," while Chuck Close has said of Turrell, "He's an orchestrator of experience."

The Skyspace represents the maturation of what Turrell begin in 1969, a series known as "stoppages," perhaps an allusion to Duchamp's pivotal Three Standard Stoppages, consisting of cuts in the wall of his studio by which he could control exterior light into the room, a process he described as a "musical score." Alanna Heiss, who founded PS1, commissioned the work for Rooms, the museum's first exhibition in 1976, but work on this Skyspace didn't begin until 1980. Characteristically, Turrell continued to make various modifications to create the desired effect, and the installation only opened to the public in 1986. Turrell said the work, a prototype for the artist's subsequent Skyspaces began with "the idea of the meeting of the space inside to the space in the sky, and feeling that juncture, having it be a visceral, almost physical feeling...Because in my work, I often took light and gave it a feeling of thing-ness, of solidity." The work has a kind of sublime effect, evoking the elemental grandeur of nature, at the same time it explores, as Turrell said, "this idea that we make color, something we're quite unaware of, that we give the sky its color." As art critic Jonathan Jones wrote, "Turrell is the last great American romantic artist, giving the viewer rhapsodic encounters with nature and the mystery of light. He proves that artists can still look at nature afresh."

Cedar, LED lighting - Museum of Modern Art P.S.1, New York

Beginnings of Light and Space

The Influence of Minimalism

In the early 1960s, Minimalism emerged as the leading art movement centered in New York City. Key traits of this era, exemplified by artists like Donald Judd and Carl Andre, include the use of industrial materials to create three-dimensional objects, often simple geometric forms, stripped of all decorative and traditional aesthetic effects. Reacting against the gestural angst of Abstract Expressionism and influenced by Russian Constructivism's use of industrial and prefabricated materials, artists including Frank Stella, Dan Flavin, Robert Morris and Tony Smith turned toward creating what Judd called "specific objects," in his 1965 essay of the same title. In his argument, Judd rejected traditional aesthetic distinctions between categories of fine art, stating: "The best new work is neither painting nor sculpture, but a paradoxical hybrid."

This idea is echoed in the writing of Morris, who also argued for the primacy of simplified form and works informed by their context in his Notes on Sculptures (1966). Such ideas permeate the Minimalist look, as manifest in Dan Flavin's iconic installations using industrial fluorescent light tubes arranged in parallel lines or geometric grids, such as "monument" 1 for V. Tatlin (1964), of which the artist made 39 different versions. Likewise, Tony Smith's Die (1963) consists of a six-foot-square steel cube placed directly on the gallery floor, emphasizing the materiality of the sculpture as an object rather than an artwork set upon a pedestal. As such, the artist advocated that the true meaning of art did not reside in the isolated sculptural form, but in the relationship created between context, viewer and object.

The Light and Space movement has been regarded by a number of art historians and scholars as a variation of Minimalism, as both movements developed nearly concurrent with one another and shared many visual traits. Most overt is the connection made between Dan Flavin's site-specific works, which he called "situations," beginning in the early 1960s with the slightly later works by Los Angeles artists Robert Irwin and James Turrell. However, there is a philosophical distinction between the two ideas. For example, Flavin emphasized the use of light as a prefabricated object, in the form of industrial fluorescent light tubes, while Irwin incorporated light as a medium, as seen (or perceived), to alter the viewer's perception in works such as the illusion of floating discs created in his Untitled (1967-68). Additionally, in Flavin's work the industrial fluorescent lights were part of the aesthetic, while many artists associated with Light and Space, such as Turrell, often concealed the source of light in their installations emphasizing the artist's concern with the effect, rather than the physicality, of the light source.

The contrast between emphasizing the object versus the experience was explored by art critic Ian Wallace in a 2014 article for Artspace in which he explained: "Light and Space artists embraced... the 'theatricality' of Minimalist sculpture that critic Michael Fried described in his important 1967 essay 'Art and Objecthood.' Emphasizing an immersive interaction with the work of art that called dramatic attention to the personal experience of the viewer." In a 2011 article for Art Critical Joan Boykoff Baron and Reuben M. Baron further elaborate on this idea, writing: "Indeed, these L.A. works could be Michael Fried's worst nightmare - their theatricality is an integral part of their aesthetic DNA. They make us keenly aware that what you do affects what you see, and what you see affects what you do."

In this respect, Fried's definition of "theatricality" applies to the Light and Space artists, who focused on the prolonged experience of the engaged viewer. However, the work of these artists might be equally understood alongside the concepts of Kinetic Art. As the Barons continue, "These works challenge our assumptions about ordinary reality to a point where, using our perceptual, sensory-motor apparatus, we try to disambiguate forms as they appear to morph before our eyes."

Robert Irwin and “Perceptualism”

After serving in the army in World War II, Robert Irwin attended several of the art colleges that would define the early contemporary art scene of Los Angeles, including Otis Art Institute (1948-50), and Chouinard Art Institute (1952-54). He then traveled through Europe and North Africa for two years before returning to Los Angeles. Upon his return, Irwin briefly taught at Chouinard, becoming an important early influence for numerous young artists, including Larry Bell and Ed Ruscha.

An engagement with, or perhaps rejection of, the prominent trend of Abstract Expressionism marks Irwin's early career. Rather than the monumentally scaled paintings typically associated with that movement, Irwin created what he called "Hand-Helds," small square paintings with handmade frames that emphasized a more intimate interaction with the viewer. From early on, Irwin was exploring materiality as a means to explore the viewer's experience, here focusing on scale, which continued as his work increasingly moved toward a Minimalist aesthetic.

Robert Irwin coined the term "Perceptualism" to refer to his burgeoning artistic theory and practice, foregrounding the stability and instability of human sensory experience as the primary 'subject' of the artwork. Eventually, the artist explored this idea using light as a primary means to investigate the relationship between the material and the immaterial. The works of the philosophers Husserl, Hegel, and, particularly Merleau-Ponty's Phenomenology of Perception (1945), which Irwin described as "so difficult that I decided the only way to read them was to read them all day," became foundational to Irwin's theory which became the theoretical framework of the Light and Space movement. As art critic Peter Frank wrote, "The basic tenet is ... what you see is not what you think you see - nor is it otherwise."

James Turrell

Born in Los Angeles, James Turrell first studied experimental psychology and mathematics as an undergraduate at Pomona College, earning his Bachelor's in 1965, followed by a year of graduate studies in art at the University of California, Irvine. He explained his movement toward art as "light-inspired." After traveling to New York to see Mark Rothko's work, then his favorite artist, he was disappointed to find the painting lacked the quality of light that he saw in the projected slides of his art history class. In 1966, he left school and rented part of the Mendota Hotel in Santa Monica where he created the first of his experimental light projection works. The young artist blacked out the windows of a room, while allowing light to pass through cut openings in the structure. This evolved into increasingly sophisticated installations composed of illusory shapes created by artificial, projected light, and marks the beginning of his life-long preoccupation with the perceptual effects of light and dark. One famous early work, titled Afrum, Pale Pink (1967), consists of what first appears to be a glowing cube, suspended in the corner of a room, but is an optical illusion created by projected light.

Soon after these early experiments, Turrell had his first solo exhibition at the newly established Pasadena Art Museum in 1967. The following year, he was invited to participate in the Los Angeles County Museum's Art and Technology Program where Turrell and Irwin requested to work in partnership, studying the effects of sensory deprivation, known as "the ganzfeld effect," and other perceptual phenomena with an experimental psychologist in a laboratory setting. Meanwhile, Turrell also continued his education, earning his MFA in Fine Art at the nearby Claremont Graduate University in 1973.

As Turrell described in the 1987 text, Mapping Spaces, "Light is a powerful substance. We have a primal connection to it. But, for something so powerful, situations for its felt presence are fragile...My desire is to set up a situation to which I take you and let you see. It becomes your experience." This interest in experimental psychology and human perception, continues to influence the artist's decades-long project at the site of an extinct volcano, approximately 40,000 years old, known as Roden Crater in northern Arizona. Of his goal in transforming the 2-mile-wide formation to create an extensive sky observatory, Turrell has said, "I'm not taking from nature as much as placing you in contact with it."

Ferus Gallery and The Cool School

In his 1974 text, Sunshine Muse: Art on the West Coast, 1945-1970, art critic and novelist Peter Plagens famously described the early Los Angeles art scene as, for all intentions, a cultural wasteland. Although there were individual examples of artistic success, there was little in terms of infrastructure beyond the art colleges, including Chouinard Art Institute and Otis College of Art and Design, supporting and connecting artists in the early post-war period. Over time, a nascent contemporary art scene began to develop. Today, the most famous example from this period is Ferus Gallery, co-founded by curator and art enthusiast Walter Hopps and artist Ed Kienholz in a storefront on La Cienega Avenue in 1959.

Ferus was among the first art galleries in the region to focus on exhibiting and promoting the young Southern Californian avant-garde during this period. The now-legendary roster includes artists and exhibitions associated with the Light and Space movement, such as Larry Bell's first solo exhibition in 1962. The gallery was also a hub for East Coast artists to show in the West, most famously exemplified by Andy Warhol's first-ever solo painting exhibition at the gallery in 1962. Shortly thereafter, Hopps became a curator at the experimental Pasadena Art Museum, where he organized the first retrospective of the pioneer of Conceptual art, Marcel Duchamp in 1963. Conceptual, Pop artist Ed Ruscha compared the art space to a jazz label, "where there are a lot of different voices under the same record label. Each had a very distinctive take on the world and on his work, and so that made it a very vital place to aspire to and to be." Although the gallery closed in 1966, it played a central role in the formation of establishing the careers of the Light and Space artists, such as Billy Al Bengston's first solo exhibition in 1958, and Irwin's in 1959.

Artforum

Artforum, founded in 1962 in San Francisco, moved to Los Angeles in 1965 under a new publisher Charles Cowles where it remained for two years before relocating to New York City where it remains in operation today. The magazine's offices were located above Ferus for its brief tenure in Southern California, and the magazine played a role in promoting the work of the experimental young artists there and throughout the city. In 1964, art critic and then managing editor of the magazine, Philip Leider, dubbed the Los Angeles art scene centered around Ferus the "Cool School", a reference that included the Light and Space artists. Beginning the following year, articles featuring artists associated with Light and Space helped generate wider interest and national viability for their work. Notably, "Larry Bell," by John Coplans, along with a statement about painting by Robert Irwin appeared in a 1965 issue of the magazine, followed by Fidel A. Danieli's "Larry Bell" in a 1967 issue. The magazine's interest in Light and Space continued in New York, as seen by Kurt von Meier's "Interview with Valentine" (May 1969), along with articles on Robert Irwin, Billy Al Bengston, and Mary Corse.

In addition, Gemini G.E.L., a publishing house and fine arts workshop founded in 1966 in Los Angeles, began by making lithographs and silkscreens but quickly evolved into creating three-dimensional multiples and sculptures that ultimately furthered the reach and appreciation of the movement.

Art & Technology

Following World War II, various aerospace and industrial technologies that were originally developed for military purposes became commercially accessible to various West Coast cottage industries. Among them, local artists began exploiting the newly available materials, including fiberglass, Plexiglas, resins and plastics, for their artistic potential. At the same time, Southern Californian universities and think tanks were conducting scientific research into the nature of human perception, sensory deprivation, and kinesthetic experience that also informed the artistic explorations of the Light and Space group.

Recognizing this dynamic relationship between disciplines, in 1967 the Los Angeles County Museum of Art launched the Art & Technology Program, supporting the intersection of the latest technology and research with art. One such project involved Robert Irwin and James Turrell with Dr. Edward Wortz, (a psychologist working for the Garrett Aerospace Corporation) exploring anechoic chambers (soundless self-contained spaces) and Ganzfelds (a form of perceptual deprivation caused by an undifferentiated and uniform visual field). Experiencing for themselves the sensory conditions, Irwin and Turrell sought to use their findings to create an experience for the viewer. Simultaneously, from 1968 to 1971, the California Institute of Technology also created a collaborative arts and sciences program, in which Helen Pashgian and Peter Alexander, the physicist Richard Feynman, industrial designer Henry Dreyfus, and John Whitney, a pioneer in computer graphics, participated.

Due to the complexity of the materials involved, the Light and Space artists often worked with engineers and technology experts to find technical solutions to achieve and maintain their visions. This resulted in long-standing relationships between fabricators such as Jack Brogan with the Light and Space artists, to create such monumental works as Irwin's prismatic columns, as well as the maintenance and conservation of Bell's glass cubes. Others, including De Wain Valentine and Fred Eversley, created their own technologies. In 1966, Valentine partnered with Hastings Plastics to produce his Valentine MasKat Resin, which made possible his monumental circles and columns, like the famous Grey Column (1975-76), a massive polyester slab standing twelve feet tall and weighing two and a half tons. Eversley, who had trained as an aerospace engineer and worked as a senior instrumentation engineer for Wyle Laboratories, used his scientific expertise to invent new ways of molding polyester resins allowing the artist to engineer highly reflective, multichromatic parabolic mirrors.

Light and Space: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Immersive environments

Among the primary ideas that distinguished the achievements of the Light and Space artists were the embrace of non-traditional artistic media. A quick survey of works consisting of glass, resin, natural and artificial light, supports this notion. However, it is important to recognize the artists' intentions providing the driving force behind the adoption of such materials. The goal of these artists was not to simply create a new style of art object, but to create a new kind of viewing experience. This is perhaps most evident in the creation of "immersive environments," which engage the viewer's entire body and sense of perception through the manipulation of light, shadow and space.

Robert Irwin, James Turrell, and Douglas Wheeler were pioneers in the creation of these immersive environments from the earliest experiments associated with this movement, as seen in Turrell's Shallow Space Constructions (1968). This project, drawing upon his recent sensory deprivation research, used screened partitions to create a flattened spatial effect. Additionally, Irwin closed his studio altogether in 1972, signaling his intention to abandon notions of art as "an object," and instead created "site-conditioned" installations, as seen in his Scrim veil - Black rectangle - Natural light (1977). "What made an artist an artist is a sensibility," he described in a 2015 interview for the Wall Street Journal, adding that without "the limitations of thinking about being a painter, you can operate anywhere in the world." Doug Wheeler's RM 669 (1969) was another early example of an immersive environment within a gallery. A vacuum-formed Plexiglas and white neon light forms the outline of a square installed on a white wall, the light emitted appears a soft blue color highlighting the shape, but also altering the mood and sense of the entire room's atmosphere.

Beginning in the 1980s, the notion of immersive environments moved from interior spaces to exterior constructions. Although this might appear to be a simple continuation of a site-specific installation to the outdoors, the interaction between the viewer, installation and location increased exponentially. Irwin described these works as "Conditional Art," distinguishing it from site-specific works which artists create to fit within a defined area. Instead, as Jonathan Griffin described in a 2015 interview with the artist for Apollo magazine, "Irwin's Conditional Art is intended to be absolutely responsive to its environment, and its objective is to enhance a viewer's perception of a space." The labyrinthic Central Garden (1997) at the Getty Center in Los Angles exemplifies this relationship, where in lieu of technology, Irwin employed natural materials, including water and plants to "accentuate the interplay of light, color, and reflection."

Turrell, who had employed natural light from the beginning, began creating his architectural installations, known as Skyspaces and Skyscapes in the mid-1970s. First cutting openings into the ceiling of an enclosed room or veranda, he combined artificial light with the exterior light to counteract the changing colors of the sky. He also began work on his Roden Crater in 1979. Still an ongoing project, work on the crater has involved moving over a million cubic yards of earth to shape the cone, as well as six planned tunnels, like the 854-foot-long Alpha Tunnel, and twenty-one viewing spaces, which art critic Colin Herd described in 2014 as a series of "transitional spaces." Addressing the Earthwork aspects of the project, Turrell has said, "You could say I'm a mound builder: I make things that take you up into the sky. But it's not about the landforms. I'm working to bring celestial objects like the sun and moon into the spaces that we inhabit."

Sculpture

Sculpture made of industrial materials and employing new technology was a dominant genre of the Light and Space movement, as seen in Robert Irwin's monumental 12- and 16-foot-tall clear acrylic columns Untitled (1969/2011), De Wain Valentine's Double Pyramid (1968), and Helen Pashgian's iridescent spheres. As Irwin noted, "The column was an indication of my wanting to get out and treat the environment itself...of dealing with the quality of a particular space in terms of its weight, its temperature, its tactileness, its density, its feel." While each of these examples seem to follow in the traditional notions of sculpture in the round, they share concepts with the ideas explored in the immersive environments. The sculptures are not simply discreet objects, but variable experiences dependent upon the ambient light and colors potentially absorbed and reflected from the object's surfaces, in relation to the viewer's position to the work.

The objects are both stoic and immovable, yet paradoxically, always appear as if in a state of flux. Art historian David F. Martin described the experience of viewing sculpture as a journey, writing: "As I move, what I have perceived and what I shall perceive stand in a defined relationship with what I am presently perceiving. My moving body links these aspects...the varying reflected light glancing off the surfaces help to blend the changing forms." This idea aptly applies to the relationship between viewer and Light and Space object, where the slightest move on the part of the viewer might result in the illusion of shape-shifting or light-bending counteractions.

Like their Minimalist counterparts, the sculpture of the Light and Space artists tends toward hard-edged geometric forms, void of the usual associations of sculpture such as figuration or podiums. In the case of Larry Bell's glass cube works, the pedestals themselves were crafted from clear acrylic, meant to create the allusion of suspension rather than a podium upon which the work was placed. In other examples, the sculptures are placed directly on the floor, often towering over the viewer, so that the objects shape the environment rather than exist within it. The same comparison might be made between the traditional relief sculpture and the wall-mounted experiments of Orr, Wheeler, Irwin and Turrell. Here, as in the free-standing works, the activation of space around the object is transformative to the environment in which they are located.

Paintings

Many of the Light and Space affiliated artists began their career experimenting with ideas related to the dominant trend of Abstract Expressionism. Looking at the earliest work, some examples culled from college experiments, such as Larry Bell's L. Bell's House (1959) during his time at Chouinard, and others in their first exhibitions - for example Craig Kauffman showed a series of Expressionist-style paintings in his first solo exhibition at the Los Angeles-based Felix Landau gallery in 1953. Alternatively, John McCracken's earliest paintings explored notions of the subconscious.

Robert Irwin and Mary Corse both moved away from notions of gesture in the 1960s and began independently creating paintings that innovatively explored the effects of light while continuing to work with pigment and canvas. Irwin's first experiments involved using two straight lines of complementary or contrasting color to horizontally dissect the pictorial plane. The lines were not intuitive marks, as might be described of the Abstract Expressionists, but theoretical, closer to experiments with perception. Art historian Carolee Thea explained the placement of thin lines within the large square canvases as, "light trying to break through a seam ... the edge seems to dematerialize ... [casting] a shadow that activated the surrounding space."

Conversely, the striped surfaces of Mary Corse's paintings consisted of broad vertical divisions of the picture plane. The monochromatic works featured bands of the same hue - most famous are the white and/or black paintings - alternately mixed with varying amounts of glass microspheres, such as those used in highway line markings. The shimmering bands reflect ambient light to different degrees reacting to the viewer's position - and so they are passively kinetic, for while they don't physically move, they appear to fluctuate depending on the viewer's position. In this way, the two-dimensional paintings of the Light and Space artists offer a viscerally sculptural experience, as the works require the active movement of the viewer in order to truly engage with the experience the artist intended to create.

Los Angeles native Craig Kauffman blurred the boundaries between sculpture and painting with his wall-mounted works, which also defy easy categorization even within a movement of such variety as Light and Space. The work also relates to notions of Finish/Fetish and has been described as having a Pop art aesthetic. Kauffman studied art at USC before transferring to UCLA in 1952, where his lifelong friend Walter Hopps was studying art history. He had his first solo exhibition at the Felix Landau Gallery in 1953, another early proponent of modern and contemporary art in Los Angeles (in operation from 1951-1971). Like Irwin and Corse, his early paintings reveal a strong influence of Expressionism, before reaching his mature experiments with vacuum-formed cast acrylic plastic. Such works present a dichotomy, for while they might easily be misconstrued as mass-produced, industrial objects, the subtle gradation of tone and translucency, as demonstrated by his Untitled (1968), were the product of his meticulous study of paint and structure and created by numerous sprayed layers of copolymer paint. The works in the series grew increasingly sophisticated, later employing iridescent paints, to heighten the variability of visual effects caused by light hitting the works' surface. Although the aesthetics and materials between Corse and Kauffman are quite different, the experience of viewing the work holds many similarities. As Kauffman described during an interview with the Smithsonian Institute, the color changes "as you change the angle of how you view it. I wanted it to kind of pulsate and be very vague about what it was. Irwin was getting into being very vague about where things were at the time too and I liked that."

Later Developments - After Light and Space

In the past decade, a series of major exhibitions have spawned critical discourse of the often-overlooked contributions of the Light and Space movement. This change was first sparked by the expansive collaboration known as Pacific Standard Time: Art in LA 1945-1980 (2011), a series of exhibitions funded by the Los Angeles-based Getty Research Institute, including the critically lauded Phenomenal: California Light, Space, Surface at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego. Soon thereafter, James Turrell had three major concurrent solo exhibitions across the United States at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 2013. At the Guggenheim, the entire spiral staircase of the museum's rotunda was transformed into a laboratory of glowing light slowly cycling through jewel-toned hues, ranging from emerald green to ruby red to sapphire blue.

Pioneering site-specific installations and immersive environments, the Light and Space movement also influenced successive generations of artists. Similar ideas of color and perception have provided a conceptual basis of experimentation for a group of abstract color theory artists, including Frederick Spratt, David Simpson, Anne Appleby, and Phil Sims. Beginning in the 1980s through today, a second generation of artists continue the legacy of the Light and Space movement through their own diverse intellectual philosophies and aesthetic approaches. Among the most prolific is Icelandic-Danish artist Olafur Eliasson, who continues the legacy of immersive installations incorporating projected and reflected light, color-stained sheets of resins and mirrors to create dichromatic effects, splitting visible light into distinct beams of different wavelengths. Of increasing influence and rising stature in the 2010s are the likes of Gisela Colon, Tara Donovan, Spencer Finch, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Andy Moses (son of "Cool School" artist Ed Moses), and Phillip K. Smith III.

Useful Resources on Light and Space

-

![Phenomenal: California Light, Space, Surface]() 4k viewsPhenomenal: California Light, Space, SurfaceOur PickMuseum of Contemporary Art San Diego

4k viewsPhenomenal: California Light, Space, SurfaceOur PickMuseum of Contemporary Art San Diego -

![Light and Space Art Movement Video | Light and Space Art Movement Video Documentary]() 0 viewsLight and Space Art Movement Video | Light and Space Art Movement Video Documentary

0 viewsLight and Space Art Movement Video | Light and Space Art Movement Video Documentary

-

![A Few Things About Robert Irwin]() 8k viewsA Few Things About Robert IrwinOur PickLos Angeles County Museum of Art

8k viewsA Few Things About Robert IrwinOur PickLos Angeles County Museum of Art -

![Introduction to James Turrell]() 53k viewsIntroduction to James TurrellOur PickGuggenheim

53k viewsIntroduction to James TurrellOur PickGuggenheim -

![James Turrell: Art & Film Honorees]() 89k viewsJames Turrell: Art & Film HonoreesLos Angeles Country Museum of Art

89k viewsJames Turrell: Art & Film HonoreesLos Angeles Country Museum of Art -

![Larry Bell: Seeing Through Glass]() 12k viewsLarry Bell: Seeing Through GlassOur Pick

12k viewsLarry Bell: Seeing Through GlassOur Pick -

![Peter Alexander: The Color of Light]() 12k viewsPeter Alexander: The Color of LightGetty Conservation Institute

12k viewsPeter Alexander: The Color of LightGetty Conservation Institute -

![De Wain Valentine: Surface Matters]() 3k viewsDe Wain Valentine: Surface MattersGetty Museum

3k viewsDe Wain Valentine: Surface MattersGetty Museum -

![Helen Pashgian: Golden Ratio]() 20 viewsHelen Pashgian: Golden Ratio

20 viewsHelen Pashgian: Golden Ratio

-

![Robert Irwin: Why Art? - The 2016 Burt and Deedee McCurty Lecture]() 18k viewsRobert Irwin: Why Art? - The 2016 Burt and Deedee McCurty LectureStanford University

18k viewsRobert Irwin: Why Art? - The 2016 Burt and Deedee McCurty LectureStanford University -

![Conversation with Robert Irwin on Light and Space III]() 25k viewsConversation with Robert Irwin on Light and Space IIIOur PickNewfields

25k viewsConversation with Robert Irwin on Light and Space IIIOur PickNewfields -

![Helen Pashgian in Conversation]() 1k viewsHelen Pashgian in ConversationOur PickGetty Conservation Institute / Conservation with Helen Pashgian with Rachel Rivenc and Carol Eliel

1k viewsHelen Pashgian in ConversationOur PickGetty Conservation Institute / Conservation with Helen Pashgian with Rachel Rivenc and Carol Eliel -

![Olafur Eliasson: Playing with space and light]() 164k viewsOlafur Eliasson: Playing with space and lightTed Talks

164k viewsOlafur Eliasson: Playing with space and lightTed Talks