Summary of Constructivism

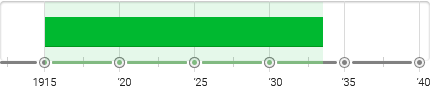

Constructivism was the most influential modern art movement in twentieth century Russia. With its aesthetic roots fixed firmly in the Suprematism movement, Constructivism came fully to the fore as the art of a young Soviet Union after the revolution of 1917. The movement was conceived of out of a need for a new aesthetic language; one benefitting of a progressive new era in Soviet socialist history. Constructivism also borrowed elements of other European avant-gardes, notably Cubism and Futurism, and at its heart was the idea that artmaking should be approached as a process of cerebral “construction”.

Released from the old romantic notion of being tied to the studio and the easel, Constructivist artists were reborn as technicians and/or engineers who, much like scientists, were seeking solutions to modern problems. By the early 1920s Constructivist art had evolved to accommodate the idea of Productivism which took the aesthetic principles of Constructivism and applied them to “everyday” art such as photography, fashion, graphic and textile design, cinema, and theater. Nevertheless, by the early 1930s the Soviet avant-garde had rudely fallen foul of the new regime that wished to promote the more transparent style of Socialist Realism.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The shared goal of the founders of Constructivism was to produce artworks and buildings using modern materials and designs that would awaken the proletariat to imperialist class divisions and other bourgeois inequalities. The Constructionists sought, in Aleksei Gan’s words, “to find the Communist expression of material construction [and] to establish a scientific base for the approach to constructing buildings and services that would fulfil the demands of Communist culture”.

- Constructivism became closely aligned with the idea of agitprop (agitational propaganda) which applied to an artwork that aimed to educate and indoctrinate its audience to the prevailing Bolshevik cause. By employing arrangements of basic industrial geometric forms and colors the new Soviet Union would be represented by the new languages of industry and modernity. However, most of the country were semi/illiterate land workers, and these remote communities were reached through Agit Trains. These featured (amongst other things) purpose-built cinemas which delivered the Bolshevik message through unambiguous propaganda films, known as agitki.

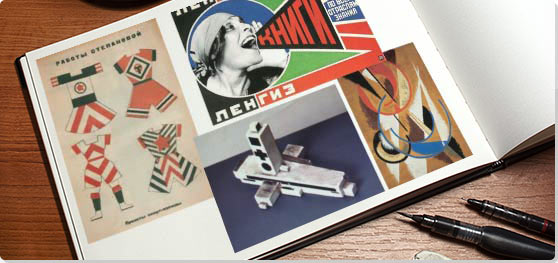

- Once evolved into Productivism, Constructivist art promoted the idea of an industrial production must directly address the needs of the proletariat. Without abandoning their commitment to basic geometric shapes and colors, Productivists moved away from abstraction and engaged with design activities including furniture design, ceramics, textile design, graphic design and advertising, and theater set design.

- Constructivist art often aimed to demonstrate how materials behaved and to test, for instance, the properties of materials such as wood, glass, and metal. The form an artwork would take would be dictated by its materials rather than in traditional art practice whereby the artist transforms his or her base materials into something different (and possibly beautiful). These inquiries were often in and of themselves. For many Constructivists, this entailed a commitment to the "truth to materials", that being, the belief that materials should be employed only in accordance with their capacities, and in such a way that demonstrated the uses to which they should be put.

Overview of Constructivism

Calling his Proun paintings "the station where one changes from painting to architecture," El Lissitzky's architectonic works became a bridge between the diverse disciplines within Constructivism.

Artworks and Artists of Constructivism

Suprematism

Malevich is considered the founding father of Suprematist art. In 1913, he had joined composer Mikhail Matyushin and poets Aleksei Kruchenykh and Velimir Khlebnikov to create the opera Victory Over the Sun. Malevich was responsible for the costume designs which he created using simple geometric shapes and colors. The stage itself resembled a square and Malevich later insisted that Victory Over the Sun was in fact the first manifestation of Suprematism. Malevich presented Suprematism as both an artform and as a bigger philosophical/spiritual worldview.

Although he was a staunch supporter of the Revolution, if one is to create pure artworks, Malevich believed, then the artist must be free and independent of all outside interests. As Malevich stated: “Under Suprematism I understand the primacy of pure feeling in creative art. To the Suprematist, the visual phenomena of the objective world are, in themselves, meaningless; the significant thing is feeling, as such, quite apart from the environment in which it is called forth”.

Suprematism, would not, on Malevich’s insistence on the “primacy of pure feeling”, be in tune with the utilitarian goals of Constructivist art. It would be superseded by the state’s preference for agitprop and a radical domestic art that spoke clearly and directly to the citizens of the new Soviet Union. Nevertheless, in its the reductive geometric shapes, and its simple colors, Suprematism had established the visual codes that would become a hallmark of Constructivist art.

Oil on canvas - Russian Museum

Constructed Head No. 2

While visiting his brother Antoine Pevsner in Paris in 1913–14, Gabo was introduced to Cubist sculpture by Alexander Archipenko and others involved with the avant-garde. He then moved with Pevsner to Oslo during the First World War. It was in the Norwegian capital that the brothers first encountered the work of Vladimir Tatlin. Gabo began to experiment with Constructivist principles, working with modern industrial materials including glass, metal, and plastic. Constructed Head No. 2, which embodies both Cubist (it bears a close resemblance to Picasso’s bust of his lover, Fernande) and Constructivist principles, was executed in celluloid and galvanized metal. Here, however, Gabo uses his materials to form his figures, rather than letting the material dictate the artwork. It was one of Gabo’s first works and pre-empted the abstract kinetic sculptures, through which he explored the relationship between space and time, and for which he would become best known.

However, Gabo (and Pevsner) baulked at the idea that art should express specific political doctrines, or that it should meet prescribed utilitarian goals. Indeed, on their return to Russia (after the Revolution) Gabo and Pevsner were alarmed to find that Constructivist art was so inextricably bound up with agitprop, that being the belief that art and propaganda were conjoined, and that art must “awaken” (or agitate) its audience to the Bolshevik cause. In response, the men co-authored the “Realistic Manifesto” of Constructivism in 1920 which was printed on newspaper and distributed on the streets of Moscow. Like the Constructivists, they espoused the value geometric shapes and industrial materials, but they insisted that “true art” must be independent of all state interests. Gabo, therefore, never “fully qualified” as a principal Constructivist and became better known, in fact, outside of Russia in Germany, England and, lastly, the United States.

Galvanized iron and celluloid - Private Collection

Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge

Malevich taught at the Revolutionary People’s Art School in Vitebsk which had been founded by Marc Chagall. Having replaced Chagall as the School’s director, Malevich formed a workshop called UNOVIS, which ran between 1919-22. The aim of UNOVIS was to promote the art of Suprematism. One of Malevich’s students was Lazar Markovich Lissitzky, better known as El Lissitzky. His Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge is a Russian Civil War propaganda poster produced in support of the Bolshevik Red Army and their fight against the anti-Communist White Army in the Russian Civil War.

Lissitzky’s lithograph is now considered one of the most iconic of all early Constructivist artworks and, in its preference for basic geometric forms and colors, it is indicative of the overlap between Suprematism and Constructivism. The image shows a red triangle (communists) penetrating a white circle (bourgeoise). The combination of red, white, and black and basic geometric shapes was symbolic of Lissitzky’s Suprematist work, while the use of words helps the viewer follow the trajectory of dominant red triangle which seems to pierce the white circle as a pin might pop a balloon. The action of red penetrating white is repeated across the image with smaller geometric shapes.

Art historians Dr. Charles Cramer and Dr. Kim Grant write, “In this poster we see not only a masterpiece of modern graphic design, but also a new application of the Suprematist visual language, which signified spiritual transcendence, into a practical language intended to convey specific ideas and information about the material world”. They observe that this might seem “like a betrayal of the aims of Suprematism” but Malevich himself supported the “practical application of Suprematism’s forms”.

Lithograph

Monument to the Third International

In 1917, with the anticipation of a socialist revolution hanging heavy in the air, Tatlin had started to conceive of a mammoth structure that would commemorate this momentous turning point in Soviet history. By 1920 he had finalized his design for the now famous Tatlin Tower, or to give it its full title, the Monument to the Third International, or Comintern, (a committee established to overthrow the international bourgeoisie and to work towards the establishment of an “international Soviet Republic”). The original Tower was a spiralling 15-foot-high wooden structure that, although never put into construction, became an emblem to Communist utopianism and, to this day, remains the great symbol of the Constructivist movement.

The Tower was a blueprint for a fully functional conference center for the Comintern and, had it been built, would, at 400 meters (1,300 feet) been the tallest steel structure in the world (not only one-third taller, but more beautiful, from a Soviet perspective, than the Eiffel Tower). The upward spiralling tower, anchored by a diagonal girder, was to include three rotating glass units. These were a cylinder, which would house the legislature and revolve once over a period of a year; a cone designed to hold the government’s executive offices, which would revolve once a month; and a smaller cylinder, that rotated daily, would house the press office. Atop this structure would sit an hourly rotating hemisphere that would contain a radio station and project Bolshevik slogans onto the clouds. The Tatlin Tower would symbolize industrialism and construction, and the dynamism of the modern age.

St. Petersburg, Russia

Stage set design for, The Magnanimous Cuckold

Popova was one of the key figures within the early Russian avant-garde. She experimented first with abstract and semi-abstract Cubo-futurist painting which featured overlapping planes and dynamic juxtapositions of shapes and colors. She arrived at Constructivism, via Suprematism, maintaining her interest in dynamism and movement, and in geometry and the efficiency of machines. By the early 1920s she had moved away from painting to follow her faith in Productivism which brought Constructivism into the everyday lives of ordinary Russians through such mediums as fabric, graphic, book cover, and stage design.

Opening at the Actor’s Theater, Moscow, on April 25, 1922, Vsevolod Meyerhold’s landmark production of Belgian dramatist Fernand Crommelynk’s farce, The Magnanimous Cuckold, brought Constructivist art into popular theater. Meyerhold was known for his “biomechanical exercises” whereby the human body was treated as an “apparatus” that would synthesize with a set which was itself conceived of as a machine. Actors would thus express themselves through forceful gestural performances that would combine with the moving set to “agitate” the audience. Meyerhold had asked Popova to design a stage that could respond to the athletic gestures and twists and turns of his performers’ nonverbal cues and, at a more practical level, to design a set that could be easily and quickly dismantled and reassembled with the view of touring the production to other Russian cities.

Historian Marc Arthur writes, “Magnanimous Cuckold was a tragic farce about a desperately cuckolded husband who punished his wife by insisting that she sleep with every man in the village […] Popova’s interactive set, consisting of multi-level platforms, staircases, revolving doors, and three wheels, the largest containing the letters “CR ML NCK” (the playwrights’ name), that could be spun by the performers, it was a hilarious, circus-like performance that was part vaudeville and part athletic demonstration. Popova also designed the boxy, primary-colored worker uniforms of the actors”.

Oil on canvas - Tretyakov Gallery

Proun Room

Of all the Constructivists, it was perhaps Lissitzky who maintained the closest ties to Suprematism. Between 1919-27, he worked extensively on his Proun (“Projects for the Affirmation of the New”) series. For this project he produced many Suprematist-inspired paintings that contrasted light and dark, and created architectural and three-dimensional space within a two-dimensional image. The effect was the illusion of geometric forms floating in space, which, for Lissitzky, was symbolic of the transformation of Russian art into a way of life.

In his Proun Room, unveiled at the Great Art Exhibition in Berlin in 1923, he extended what had been two-dimensional works into an installation. His Room consisted of geometric shapes, in colors of black, white, and gray, and linear wooden vectors that reached across floor, wall, and ceiling (six surfaces in all). Lissitzky was exploring the idea that art should establish a new and elementary balance between art and living space and his ideas exerted great influence over the teachings at the Bauhaus and De Stijl schools.

Installation - Great Art Exhibition, Berlin

Self-Portrait (The Constructor)

El Lissitzky, with others such as Alexander Rodchenko, Gustav Klutis, Valentina Kulagina, Varvara Stepanova, and the Stenberg Brothers, created photomontages in support of socio-political goals of the nascent Soviet Union. But while his colleagues (comrades) used photomontage to support the Productivist programme (through product advertisements) Lissitzky combined his photographs in multi-layered compositions, stayed closer to his Suprematist roots. In one of his most famous compositions, Self-Portrait (The Constructor), he combined elements of collage, technical drawing, and photography in a way that emphasises mathematical form and geometric grids. Lissitzky, stares fixedly forward, while his right eye seems to look through the center of his open palm. The same hand balances a compass over one of his graphic works, partially depicted, on the left side of the frame. The work symbolizes the unity of artistic vision and execution and suggests the Constructivist artist is both the constructor of his work and is constructed by it. Photographic archivist Klaus Pollmeier says of the image, “He seems to have visualized many aspects of the final image before the exposure of the negative in the camera, compensating for the shortcomings of his limited technology with a sharp and almost boundless imagination”.

Lissitzky was perhaps the most influential of the Constructivists on the international avant-garde scene. He arrived in Berlin (with a population of over 500,000 Russian expatriates) in 1921 as Russia’s Cultural Ambassador. His role was to re-establish links with the West following the First World War and the Russian Revolution and to that end he co-edited, with Ilya Ehrenburg, the magazine, Veshch-Gegenstand-Objet, which championed Constructivist and Suprematist art. Although it only published two issues (the third and fourth editions were banned from distribution in Russia making it uneconomical to publish) it did much to establish International Constructivism on the European art scene.

Gelatin silver print - Victoria and Albert Museum, London, United Kingdom

Books (Please)! In All Branches of Knowledge (Advertisement Poster for the Lengiz Publishing House)

In their quest to move art beyond the confines of the gallery and into the sphere of everyday life, Constructivism was naturally drawn to the field of graphic design (the marriage of text and image). The greatest exponent of poster art was probably Rodchenko whose iconic designs employed bold typography, vivid colors, and geometric forms. Perhaps Rodchenko’s most iconic work was, Books (Please)! In All Branches of Knowledge (1924). It is a photomontage featuring a joyful female worker shouting the titular cry. Rodchenko’s striking combination of photography, geometric lines, and bold color, brings to the work an almost sonic quality.

Starting his career as a fine artist, Rodchenko’s total commitment to the new Russia saw him abandon avant-garde experimentation in the cause of Productivism. The idea of consumerism and a market economy might seem to rub against the ideology of Communism. Yet several artists worked in the field of advertising creating graphic advertisements for co-operative businesses such as the state-owned department store, Mosselprom. Indeed, Rodchenko, with Vladimir Lebedev, Vladimir Mayakovsky, and Valentina Kulagina, became involved in the creation of so-called “ROSTA Windows”. Between them, these artists produced approximately 1,500 works of graphic design that were published by ROSTA (Russian Telegraph Agency) and pasted in vacant street windows. The posters tended to blend photography with bold geometric forms and, in keeping with the aims of agitprop, the posters often aimed at mobilizing the workforce and addressed both male and female workers.

Still from Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera

In 1923, Dziga Vertov published his “Kino-Eye” (Cinema Eye) manifesto. He wrote: "I am an eye. A mechanical eye […] This is what I am, a machine that runs in chaotic manoeuvres, recording movements one after the other, assembling them in a patchwork. Freed from the constraints of time and space, I organize each point of the universe as I wish. My route is that of a new conception of the world. I can make you discover the world you did not know existed”. Although not to everyone’s tastes (Eisenstein, probably Russia’s greatest exponent of formalist filmmaking, dismissed the film as “pointless camera hooliganism”), his Man with a Movie Camera stands as the pinnacle of his vision and many believe that it was the last of the great Soviet agitprop films (in 2012 the British Film Institute’s journal, Sight and Sound, voted Man with a Movie Camera 8th in its survey of the best films ever made).

The film, divided into six numbered sections, has no human agent to carry a plot with that role taken on by the camera (operated by Vertov’s brother, Mikhail Kaufman). It represents “day in the life” scenarios in three unidentified Soviet cities (it was shot in Moscow, Kyiv, and Odesa) that are populated with people from different economic classes. The movie, co-edited with Yelizaveta Svilova (Vertov’s wife) makes use of any number of avant-garde montage techniques – precipitous juxtaposition, double-exposure, slowed down, speeded up, and stop motion photography (a walking camera tripod, for instance), superimposition (the cameraman filming from inside a beer glass for instance), and so on – and is described in its credits as an “experiment in cinematic communication of visible events”.

MoMA of New York said of the director, “Like others of his generation, Vertov believed that the creation of an objective ‘cinema eye’ would, in destroying old habits of viewing, help build a new, proletarian society”. Indeed, on the film’s release, Vertov (who just a few years earlier had been honing his technique on agitki propaganda films for the Agit Trains) issued a statement which read: “This new experimentation work by Kino-Eye is directed towards the creation of an authentically international absolute language of cinema on the basis of its complete separation from the language of theatre and literature”. However, Vertov’s unwavering commitment to avant-garde experimentation saw him marginalized by the early 1930s when Constructivism (in Russia at least) was rudely usurped by Socialist Realism.

The Results of the First Five-Year Plan

Photomontage became, perhaps, the favored medium of avant-garde artists such as El Lissitzky, Rodchenko and Stepanova. Stepanova (Rodchenko’s life partner) was a leading member of this group and later in her career she contributed to the journal USSR in Construction which published between 1930-41. The journal, which was published in English, was intended mostly for overseas markets, and was a propagandist publication that celebrated Russia’s technological, agricultural, and social progress under the totalitarian rule of Joseph Stalin. But the journal was unusual in that it published images that went against the regime’s preference for Social Realist art.

Stepanova restricts this image to three color tones – black, white, red - with red geometric planes giving the photomontage a sense of narrative structure. The montage features found photographs which sit in front of her geometric planes. The speakers and the number 5 on the left reference Stalin’s Five-Year Plan and the letters CCCP (USSR) face the dominant portrait of Lenin, the founder of the Soviet Union (who, incidentally, had not liked Constructivist art but backed its goals and principles) who is looking forward towards the future. Art historian Jessica Watson writes, “Historical hindsight can make it difficult for contemporary viewers to engage the overtly propagandistic aspects of these images, in fact their exaggerated euphoria can even be mistaken for irony. Nevertheless, despite our increasingly sophisticated understanding of the distinction between image and reality, Stepanova's photomontages are an important reminder of how an artist can blur the line between aesthetic passion and ideology”.

State Museum of Contemporary Russian History, Moscow

Beginnings of Constructivism

Roots in Suprematism

Suprematism was a radical abstract art that, mostly through the efforts of Kazimir Malevich, went in search of a “zero degree” in art; that being the point at which art could be reduced to its “vanishing point”. Malevich reduced art to basic shapes (squares, circles, crosses) as a means of making art that was about the “supremacy of feeling” over pictorial art that was always about “meaning”. In 1915, Malevich was joined by Russian artists Kseniya Boguslavskaya, Ivan Klyun, Mikhail Menkov, Ivan Puni, Olga Rozanova, and Lyubov Popova. They announced themselves as the Suprematist group at The Last Futurist Exhibition of Painting 0.10.

Commenting on Malevich’s famous Black Square (1913-15) art historian Charles Harrison stated that he did not believe “that ‘revolutions’ in art cause social revolutions or provoke wars. [Rather] the faith in human capacities which impelled those [such as the Suprematists] who entertained ideas of abstract art may have been realistic to this extent: firstly that the form of faith involved may have been consistent with the state of mind (the bravery) required to envisage a progressive social and historical change, and secondly that there may have been practical grounds for believing such a change was worth pursuing”. While the “difficulty” of Suprematism made it unsuitable for the political Constructivism agenda, the link between Suprematism and Constructivism was nevertheless pursued by the likes of Alexander Rodchenko and El Lissitzky (both of whom had worked in the Suprematist idiom) who took its basic colors and shapes, and the idea of movement, forward in the name of Constructivist goals.

History usually attributes the birth of Constructivism to two artists, Vladimir Tatlin and Kazimir Malevich, both of whom had been associated hitherto with the Cubo-Futurist movement (an amalgam of Cubism and Futurism). On a visit to Pablo Picasso’s Paris studio in 1913, Tatlin became mesmerized by a series of three-dimensional wooden reliefs. Following Picasso’s influence, he produced his own abstract assemblages which he called Corner Counter Reliefs. The reliefs constructed primarily from metal and wood, were “a new kind of object” (somewhere between sculpture and architecture) and were unveiled to the public at the “Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0,10” in Petrograd in 1915-16. At the same exhibition, Malevich revealed his Suprematism paintings which were composed of basic geometric forms and colors that, when placed against a plain white background, appeared to “float” in space. Suprematism was, in the words of its creator, the search for “supremacy of pure feeling of perception in pictorial arts”.

Also in 1916, Wassily Kandinsky, one of the earliest pioneers of abstract art, had returned to Moscow (from Germany) where he mixed with some of the key names (Tatlin, Malevich, Alexander Rodchenko, Lyubov Popova, Varvara Stepanova and Naum Gabo) in the burgeoning Constructivist movement. Kandinsky supported state funded proletariat arts and education initiatives - such as Proletkult (“proletarian culture”), a country-wide proletariat arts program established by the Bolsheviks in 1917 - but Kandinsky’s relationship with Constructivism was uneven and short lived. One of his most vocal critics was Stepanova, who (having served as assistant director of the art and literature section of IZO Narkompros, a government agency charged with the enlightenment of the people through culture) argued that educators should be able to “characterize and express” artistic concepts “in words” and through clear channels of communication. Kandinsky’s search for pure spirituality rubbed against these utilitarian goals and, in 1921, he accepted an offer from Walter Gropius to join him at the Bauhaus.

Agitprop

The disjunction between Suprematism and Constructivism can be attributed chiefly to the idea of agitprop (agitational propaganda). The Suprematist’s search for the “supremacy of feelling” was overtaken by the idea that domestic art (ergo Constructivism) should explicitly support the interests of the nascent Soviet Union. It was a state backed policy that even warranted its own bureau, The Communist Party’s Department of Agitation and Propaganda (established in 1920). The term itself refers to the idea that art and/or popular culture would become politicized and act as a vital tool in the promotion of political ideology. To be fully effective, agitprop had first and foremost to “grab the attention” of its public and, moreover, (if it was to reach its potential) agitprop would need to reach beyond the confines of the museum and art gallery. Historian Kevin Brown makes the point that the Bolsheviks “came into power under the guise of popular support” when this was in fact “far from the truth” and that the regime had “seized power against the will of the majority”. To gain the “will of the majority”, therefore, the Bolsheviks initiated a ''’cultural' bureaucracy for whom culture was only a form of propaganda, and propaganda the highest form of culture".

Brown describes how “Agitprop theatre was used after the October Revolution to indoctrinate the working proletariat”. It was a style of theatre that “quickly and easily spread the Bolshevik's political message, as it evoked a powerful emotional reaction from spectators”. Indeed, Brown explains how the “accessibility, mobility, and spontaneity of these productions made them perfect for Bolsheviks who, without agitprop theatre, had no way of making contact with the working class”. One of the devices employed by agitprop theater troupes was the so-called “Living Newspaper” whereby actors “read newspapers aloud to a large group of people [and to] liven up these events, actors began to perform the news, ‘using music, clowns, acrobats, cartoon style, and montage techniques’". But the Bolsheviks had also to spread their dogma beyond its industrial city/centers, and for this purpose, cinema would emerge as a more effective means of agitprop.

Agit Trains

Historian Adelheid Heftberger explains how, in 1919, Anatolii Lunacharskii “The Soviet People’s Commissar of Enlightenment”, stated that “Education in the wider sense of the word consists in the dissemination of ideas among minds that would otherwise remain a stranger to them. Cinema can accomplish both these things with particular force: it constitutes, on the one hand, a visual clarion for the dissemination of ideas and, on the other hand, if we introduce elements of the refined, the poetic, the pathetic etc., it is capable of touching the emotions and thus becomes an apparatus of agitation”. Given the fact that most rural communities had never seen the moving image before, the simple agitki (propaganda films), became the key medium for the dissemination of Bolshevik propaganda. (It would be another five years or so before the Russian Formalist cinema reached, through individuals who had cut their teeth on the production of agitki movies, the artistic and political goals that Lunacharskii had envisioned.)

The “agitation-instructional trains” were initiated as early as 1918. They consisted of 16 to 18 carriages and became the key means by which the Bolsheviks would disseminate their political dogma amongst Russia’s rural population, most of whom were illiterate or semi-illiterate peasants, or children. The trains, which also serviced Red Army soldiers fighting in the civil war, distributed printed media (pamphlets, brochures, newspapers etc.) and, as the historian Michael Russell notes, the train carriages were “distinctively and brightly decorated with paintings and slogans [by Constructivist] artists of the standing of [Vladimir] Mayakovsky and El Lissitzky”. Agit-Trains were also equipped with newsreel filmmaking facilities and a cinema carriage. The Agit-Train initiative proved so successful it was applied to the waterways where, between 1919-20, the Red Star (Krasnaia zvesda) steamer cruised the length of the Volga River. It docked at various points where visitors boarded to watch agitki films. It is estimated that during this period, the Red Star presented some 400 screenings, attended by a total audience of around 500,000.

Productivism

Often, movements are launched with the publication of a manifesto, but by the time Aleksei Gan published Konstruktivizm, which coincided with the official formation of the new Soviet Union in 1922, the movement was moving into its Productivism phase. Challenging the pure abstraction of Suprematism, and sculptor Naum Gabo's contention that Constructivism should devote itself solely to the exploration of abstract space and rhythm, Gan introduced his manifesto with the blunt avowal: “WE DECLARE UNCOMPROMING WAR ON ART!” (original casing).

The Institute of Artistic Culture (INKhUK), which existed between 1920-24, involved artists, graphic designers, painters, architects, scholars, and sculptors who debated the purpose and function of Bolshevik arts and culture. From these debates grew the idea of Productivism. The essence of Productivism was based on the socio-economic principle that societal growth could only be truly measured by that society’s levels of productivity. The belief was that this idea could be transferred to the arts once Constructivists abandoned obscure avant-garde experimentation and committed to industrial-like working practices. It was a philosophy backed by the likes of Rodchenko, Stepanova, Tatlin, Malevich, Lissitzky, Popova, and the Stenberg Brothers who engaged with activities ranging through furniture design, ceramics, clothing design, typography, advertising, and theater set design.

In the Productivist spirit, Tatlin turned his talents to designing furniture, worker’s clothing and even a fully functioning stove. Others introduced Constructivist design into advertising for workers’ co-operatives using bold and spare colorful geometric designs. Rodchenko, Stepanova and Mayakovsky, even went by the name “advertising constructors” and produced print advertisements promoting commodities ranging from cooking oil, through confectionary and bakery items, to beer. For her part, Stepanova ventured into the field of textile design. In 1926 the artist and critic Boris Arvatov published Art and Production which acted as a manual for Productivist art. However, by the end of the decade Productivism had, like all forms of Constructivism, been all-but abolished under a Stalinist regime which threw its support behind the more immediate Socialist Realist art.

Concepts, Styles and Trends

Architecture

Constructivist architecture grew from the radical theories on design as espoused by Tatlin, Lissitzky, and Malevich. Their ideas translated into architectural jargon as “stereometric forms” which described an architectural style purged of all decorative elements and all references to past styles. Architecture historian, William C. Brumfield, explains how the Institute of Artistic Culture (INKhUK), “attempted to establish a science examining analytically and synthetically the basic elements both for the separate arts and for art as a whole”, but that its “first program curriculum, developed by Kandinsky, was found too abstract by many at INKhUK”. Despite differences in opinion over the future of Constructivist architecture, there was, nevertheless, a shared “concern for the relation between architecture and social planning [and all sides] insisted on a clearly defined structural mass based on uncluttered geometric forms and drew inspiration from modernism in painting and sculpture”.

In what is arguably the most iconic of all Constructivist artworks, the 400 meters high Tatlin Tower prototype (or to give it its full title, Monument to the Third International), unveiled in 1919, offered a utopian vision of post-revolutionary Russian architectural design. The hollow spiralling steel tower housed a series of geometric sculptural forms but was quickly dismissed by members of INKhUK as impractical. However, Tatlin’s iconic edifice, in the words of Brumfield, “gave notice of a new movement that glorified the rigorous logic of undecorated form as an extension of material and that intended to participate fully in the shaping of Soviet society”. It was not until the mid-‘20s, however, that working Constructivist structures came to fruition (in Moscow and other Russian cities) through the efforts of pioneering figures such as Alexander Vesnin and Moisei Ginzburg.

Sculpture

There were many overlaps between Constructivist artforms, not least in sculpture and architecture. Discussions on Constructivist sculpture typically begin with Tatlin’s Tower (1919) because it amounted to an attack on the “carved” and “cast” academic sculpture which it replaced with a preference for modern industrial materials (steel, glass, plastic and so on). The Constructivist sculpture thus rejected the academic principles of harmony in “mass” and “volume” in favor of constructed geometric forms that embraced the aesthetic quality of the mechanical age.

However, not all Constructivists bought into the functional element of Constructivist art. Some, such as Naum Gabo, rejected Tatlin’s design because of its emphasis on function. Gabo’s geometric sculptures used Constructivist materials such as glass, plastic, and metal but, in 1920, he and his brother, Antoine Pevsner, wrote and distributed their “Realistic Manifesto” (of Constructivism) in which they asserted that art should function independently of all state interests. They wrote: “The plumb line in hand, eyes as precise as a ruler, in a mind as tense as a compass … we construct our work as the universe constructs its own, as the engineer constructs his bridges, as the mathematician formulates his orbits“. Gabo maintained that art (if it was to be timeless) should be about energy, force, and rhythm. In 1920 he produced, Kinetic Composition, in which a motor rotated a steel blade as a demonstration of relations between of space and time. Gabo’s sculpture is the first known work of Kinetic Art.

Photomontage

Photomontage has been the medium of choice for producers of propaganda and agitprop. Following in the vein of the Dadaists, the Constructivists favored the photographic image because it communicates with an immediacy and objectivity that can be lost with painting and written text. Indeed, Lissitzky declared that "No form of representation is so readily comprehensible to the masses as photography”. By combining images with text, photomontage was seen as a modern, attention-grabbing, technique that was perfectly suited to the goals of Bolshevik agitprop.

Figures such as Rodchenko, Stepanova, Gustav Klutis and the Stenberg Brothers showed their support for formalist cinema by creating posters (and also film prospectuses, advertisements, periodicals and even promotional photocollages and maquettes). Indeed, the film poster became a Constructivist artform in its own right and its greatest exponents were the Stenberg Brothers. As Vladimir Stenberg put it: "Ours are eye-catching posters, designed to shock. We deal with the material in a free manner. . . disregarding actual proportions. . . turning figures upside-down; in short, we employ everything that can make a busy passerby stop in their tracks. The inventive results included a distortion of perspective, elements from Dada photomontage, creative cropping, an exaggerated scale, a sense of movement, and a dynamic use of color and typography, all of which created a revolutionary new art form: the film poster".

Textile Design

Following the Revolution, Russia had become distanced from the major international fashion centers (notably, Paris). Addressing the need for new designs in clothing and other textiles, artists like Varvara Stepanova and Lyubov Popova worked on new designs geared specifically towards mass production. Both worked at the Tsindel (First State Textile Factory), for who they produced over 150 designs, and both taught textile design at Vkhutemas (Higher Technical Artistic Studios). In fact, the two women were, as art historian Christina Kiaer notes, “the only Constructivists to see their designs for everyday, utilitarian things actually mass-produced and distributed in the Soviet economy”.

Stepanova was perhaps the most influential women in the Constructivist movement (Popova’s career was cut short by disease in 1924). She had an oeuvre that encompassed painting, poetry, photography, graphic design, and set design and was the life-partner of Rodchenko. The fashion historian Jacob Charles Wilson writes, “The workers of the new world would live and play in the very best materials and designs: casual jumpsuits and overalls that drew on both traditional peasant clothing and the latest modernist artistic trends of futurism and cubism. Stepanova’s designs use dynamic shapes that emphasise the human body in action, with sharp angular forms, printed abstract patterns and contrasting colours: bold reds and blacks. Her clothes would enhance the flexibility and comfort of moving through the streets and the city, in the factory and on to the playing field, while unisex clothing patterns would no longer confine men and women to stifling gender norms”.

Constructivism and Cinema

In 1923, Constructivist artists organized themselves into a sub-group called “Left Front of the Arts” under whose name they produced the highly influential avant-garde journal LEF, (1923–25), and then, New LEF (1927–29). The journal defended the avant-garde against the rise of Socialist Realism and the threat of a rebirth of a traditional bourgeois/capitalist art. For the contributors of LEF, the medium of cinema held the greatest potential for defence against easel painting and traditional narratives. Pioneers of the Formalist cinema, some of whom had cut their teeth on the Agit Train films, agitki, were Sergei Eisenstein, Lev Kuleshov, Vsevolod Pudovkin, Esther Shub, and Dziga Vertov.

A former student of Lyubov Popova, Eisenstein was the most influential of the group. He developed five stages of dialectical montage – metric, rhythmic, tonal, over tonal, intellectual – that combined to bring a revolutionary dynamism to commercial filmmaking. He wrote in his famous treatise on montage, The Film Sense, “the fact [is] that two film pieces of any kind, placed together, inevitably combine into a new concept, a new quality, arising out of a juxtaposition”. Battleship Potemkin features what now ranks as one of the most influential sequences in the history of international cinema: the Odesa Steps sequence. The film told the true story (occurring in 1905) of a mutiny against a tyrannical ship’s officer. The final straw comes when the men are served with rotten meat at their mealtime. Their revolt spills onto the streets of the port town of Odesa (now Ukraine) where their uprising is supported by the ordinary citizens (comrades) of Odesa. The protesters are then mercilessly mown down by a Cossack army on the famous Odesa Steps. In Eisenstein’s model, shot A: thesis, is placed next to shot B: antithesis, which results in C: synthesis. This process, which disobeys all rules of temporal and spatial continuity, demands an intellectual engagement from the viewer and, in theory, the audience is transformed (agitated) from passive to active spectators.

Later Developments - After Constructivism

Constructivism had, following a steady decline, all but ceased in Russia by the early 1930s. The movement had fallen victim of Stalin’s hostility to intellectualism and avant-garde art and gave way to the new regime’s preference for Socialist Realism. Nevertheless, the style of Constructivism (now divested of its original political purpose) would continue to inspire artists in the West, firstly as a movement called International Constructivism which, initiated by El Lissitzky (who was appointed Russia’s Cultural Ambassador to Weimar Germany in 1921), flourished in Germany in the 1920s, and which endured into the 1950s. Its style extended across typography, exhibition design, photomontage, and book design.

Lissitzky's Proun forms influenced the industrial design of László Moholy-Nagy (who was Course Director at the Bauhaus) and, in the Netherlands, Constructivist principles influenced the De Stijl movement. Constructivism also found a home in England through Naum Gabo who resided, before and during the Second World War, on the Cornwall coast where he joined Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth, and others as a member of the St. Ives movement. Constructivism crossed the Atlantic, too, with the sculptor George Rickey penning what is often cited as the first comprehensive guide to Constructivism, in 1967.

Constructivism also found a home in Latin America during the 1950s and 1960s with Brazilian artists Lygia Clark and Helio Oiticica gaining recognition for a series of neo-Constructivist works. These pieces shared many formal similarities with Russian Constructivism, and their work also carried an element of agitprop in that it sort to “activate” their audience with pieces that could be rearranged or even worn performatively, as in Oiticica’s Parangolés (1964–79). These were layered nylon, burlap and gauze capes made with colored fabrics containing photography, painting, pebbles, straw, and shells, and even text carrying political and poetic messages. Participants would wear the capes and express themselves through movement and dance.

Useful Resources on Constructivism

- The Struggle for Utopia: Rodchenko, Lissitzky, Moholy-Nagy, 1917-1946By Victor Margolin

- The Artist as Producer: Russian Constructivism in RevolutionOur PickBy Maria Gough

- Art of the Avant-Garde in Russia: Selections from the George Costakis Collection (1981)Our PickGuggenheim Exhibition Catalogue / By Margit Rowell, Georgi Costakis, Angelica Zander Rudenstine

- Imagine No Possessions: The Socialist Objects of Russian ConstructivismBy Christina Kiaer

- Russian ContructivismBy Christina Lodder

- Rodchenko & Popova: Defining ConstructivismBy Margarita Tupitsyn