Summary of Antoni Gaudí

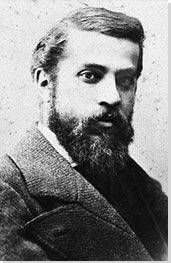

It is difficult for us today to believe that the most famous modern Spanish architect met his demise when, at age 73, he was run over by a tram and assumed to be an ordinary beggar for a full day before he was finally identified, too late to be nursed back to health. Yet Antoni Gaudí's pious Catholicism and devotion to a spartan regimen had come to define his character almost completely by the last decade of his life, which he devoted almost exclusively to the construction of his arguably most famous work, the Sagrada Família church in Barcelona. Over Gaudí's nearly fifty years of independent practice, he concocted and realized some of the most imaginative architectural forms in history, all of them in his native Catalonia, which have since become synonymous with the region's identity. The best-known - and most individualistic - representative of Catalan Modernisme (Art Nouveau), Gaudí has fascinated and inspired generations of architects, designers, and even engineers. Today his work attracts a global following with some of the most distinctive, idiosyncratic, and recognizable designs of all time.

Accomplishments

- Gaudí's was highly innovative in terms of his explorations of structure, searching through a variety of regional styles before seizing on the parabolic, hyperbolic, and catenary masonry forms and inclined columns that he developed through weighted models in his workshop. These are often integrated with natural and highly symbolic religious imagery that encrust the structure with vibrant, colorful surfaces.

- Gaudí's work is the most inventive, daring, and flamboyant of Catalan Modernisme (the Catalan strand of Art Nouveau) designers, but it is not uncharacteristic of the movement as a whole.

- Gaudí's work is highly personal, in part due to his devout Catholicism, a faith that became increasingly fervent as his career progressed. In part because of this, his work contains many references to religious themes, and he increasingly led an ascetic existence towards the end of his life, even giving up all other commissions to focus on his designs for the church known as the Sagrada Família.

- Gaudí often collaborated with several other Catalan designers, industrialists, artists, and craftsmen on his projects, most prominently Josep María Jujol, who was often responsible for the broken tilework (trencadís) that is common to much of Gaudí's buildings. This helps to explain why Gaudí's structures often feature such a wide variety of materials, used in inventive and clever ways.

Important Art by Antoni Gaudí

Casa Vicens

The Casa Vicens, opened to the public for the first time in 2017, is often considered Gaudí's first significant work. Conveniently for Gaudí, the project was a residence for the tile and brick manufacturer Manuel Vicens i Montaner, who had just inherited the land from his mother-in-law when he hired Gaudí in 1877, though construction would not start until 1882. As a result, Gaudí had a ready supply for much of the building materials, and the structure itself shows off the capabilities of Vicens' factories, functioning as an advertisement for its owner's business ventures, the Barcelona construction industry, and the skill of the region's prodigious craftsmen.

Gaudí's design, in the neo-Mudejar (neo-Moorish) style that references the Islamic architecture of medieval Spain, is poised specifically to take advantage of these readily-available construction materials. The red brick structure, with stone infill, uses sawtooth patterning, stepped arches, elaborate bracketing under protruding balconies, pointed arches, and rooftop turrets to demonstrate the various constructive properties of the material. Similar strategies are used with the skin of green-and-white checkerboard-patterned and floral ceramic tile that create a kaleidoscope of color - features common to Muslim architecture.

The connection with nature, characteristic of Art Nouveau, which this building helped develop in Barcelona, can be seen both inside and out. Not only is it featured in the tile, but the ironwork of the fence (which used to encircle a more extensive set of gardens than that which exists today) features a prominent motif of the Margallo palm, a plant native to Catalonia, and the iron grilles over the windows bear a striking resemblance to twisted vines. These natural motifs extend to the interior, where the dining room's domed ceiling has been painted to resemble looking upwards to the sky, embellished with plants and floral imagery.

Brick, stone, iron, ceramic tile - Barcelona

Palau Güell

The textile magnate Eusebi Güell's relationship with Gaudí began some eight years before he commissioned the architect to design his principal residence in the El Raval neighborhood in central Barcelona. Gaudí did not disappoint his patron. The house is approached by a double arched entryway covered with dramatic looped vine-like ironwork which allows for the entrance of horse-drawn carriages through one archway and their exit through the other. Between the twin arches sits a massive piece of wrought iron resembling tangled seaweed or a horsewhip; at the center is a banner with the characteristic stripes of the Catalan flag, disclosing Gaudí and Güell's staunch regionalism.

The interior design is focused on an ingenious square-plan central space that extends upwards four stories through the heart of the edifice and functions as a large reception hall for guests, who meet with somewhat of a surprise as they must turn around to enter from the top of the stairs leading up from the garage below. The more private spaces, as is traditional in an urban European palazzo, are located on the upper floors, with hidden windows overlooking the reception space that give the residents the chance to glimpse their guests in advance of meeting them below. Also ingeniously, the reception hall is covered with a high paraboloid domed ceiling painted dark blue to resemble the night sky; Gaudí perforated it with small holes so that lanterns could be hung above (inside a tall spire that caps the ceiling) so that the glow filtered into the space below resembled twinkling stars. The overall effect seemingly transformed the interior reception hall into an exterior courtyard illuminated by starlight.

Stone - Barcelona

Colònia Güell

Gaudí's second large project for Eusebi Güell, the Colònia Güell at Santa Coloma de Cervelló, just west of the city of Barcelona, is noteworthy for two reasons. In the first place, it demonstrates the way Gaudí and his patron understood the potential of modern architecture to shape and transform the lives of people from all different classes in both material and spiritual ways; and second, it was a means by which Gaudí continued to refine the parabolic system of structure that became virtually a hallmark of his later work.

The Colònia Güell was a means by which Güell sought to quell the tendencies towards anarchism and socialism shown by workers in many large cities, including Barcelona, at the turn of the century. He selected thus a rural location for his factory town, and provided his workers with the facilities needed for their education, health, governance, and spiritual well-being. The latter was intended to be provided by a large stone church with several parabolic spires, ornamented with ceramic tiles and designed by Gaudí in 1898, though the foundations for it were only laid in 1908.

Gaudí's designs for the workers' houses used a humble, neo-Mudejar architectural style reminiscent of his earliest works, and many of the service buildings were constructed by his assistants, such as Francesc Berenguer. Architecturally, the most important part of the complex is the church (whose design is pictured here), conceived by Gaudí using a weighted model of interlaced strings hung upside down from the ceiling in his studio in order to work out the properties of the parabolic structure of the main sanctuary space. This model is on display now in the Sagrada Família Museum in Barcelona, and undoubtedly influenced Gaudí's design for the massive urban church and its eighteen spires. Güell's continued difficulty in funding the massive Colonia project meant that only the church's crypt - supported by inclined, flattened arches and an undulating, vaulted ceiling delineated inside by massive stone ribs - was completed before his sons abandoned the project after his death in 1918.

Santa Coloma de Cervelló Spain

Casa Batlló

The Casa Batlló is unusual among Gaudí's works in that it comprises a renovation of an existing structure, originally built in 1877. Josep Batlló, the house's owner since 1900, commissioned Gaudí thinking that he would tear the building down and start anew, but Gaudí convinced him to merely renovate it. Located on the Passeig de Gracia, one of the main boulevards in central Barcelona, the house sits adjacent to the Casa Amatller (1882), designed by Josep Puig i Cadafalch, and down the block from the Casa Lleó Morera, designed by Lluis Domenech i Montaner; both of these are grand Modernisme houses and together with the Casa Batlló they form a group colloquially called the "Apple of Discord" due to the way each seems to be jockeying against the other for curb appeal. Gaudí knew he had to create a building whose forms would daringly hold its own against these other examples.

The ultimate (re)design has often been termed the "House of Bones" due to the cage-like framework over the second-floor windows, whose vertical members resemble the shapes of human bones with their slender curves. The comparison is apt, as the house appears to have no straight lines anywhere in its design; the light fixture above the dining room table is set into a blue ceiling whose spiral contours appear like water circling a drain. The facade surface is covered in intricate trencadís tiles mixed with glass, giving it a shimmering effect among the various sculptural balconies, which appear like face masks that could be used by revelers during Mardi Gras. Day and night (when it is lit artificially), the building acts as a magnet of attention like a huge vertical sheet of intricately arranged jewels, thus bringing new energy into an ordinary, unremarkable structure.

Most important, however, is the symbolism at the top of the structure, which includes a tower crowned by a cross, studded with the tiled monograms of Jesus, Mary and Joseph of the Holy Family in the Christian tradition. This turret rises from an undulating roof covered in iridescent tiles. It is said that the form of the turret is supposed to resemble the hilt of the sword of St. George, the patron saint of Catalonia, whose blade is piercing the skin of the dragon that he slays. In this way, the building indicates the deeply personal nature of the design, reflecting both Gaudí's regionalism and his mindfulness of Catholicism.

Stone, tile, iron, glass - Barcelona

Two-person sofa for the Casa Batlló

Gaudí's furniture is sometimes overlooked when considered in the context of his buildings and richness of his entire interior environments. Yet the individual pieces still hold their own under close examination, especially given their unconventional appearance, even in comparison with furniture from other Art Nouveau designers. Many of them have been reproduced in the decades since the architect's death from his original specifications.

This two-person sofa from the Casa Batlló is emblematic of Gaudí's designs, with a rather spindly frame of five legs that reflects an economy of materials. The two seats share an armrest in the center that is no larger than the exterior ones as well as the leg that supports it. Meanwhile, the irregularity of the panels for the back and seat make them appear to have been taken from whatever materials were available. The connection with nature is likewise emphasized by the shapes of these panels, particularly the backs, which appear like apples, as well as the frank exposure of the wood grain. Despite the sofa's strange appearance, Gaudí has been praised in recent years for the ergonomic qualities of his furniture, which is supposedly quite comfortable and intended to accommodate the natural contours of the human frame. It thus speaks to Gaudí's ability to design every aspect of his spaces with care and precision.

Ash - Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya, Barcelona

Parc Güell

The last project Eusebi Güell entrusted to Gaudí was a speculative hillside suburban community located on Carmel Hill, a rugged piece of terrain he had bought east of central Barcelona, to be called the Parc Güell. The impetus for the project was the Garden City Movement in Great Britain that grew out of the ideas of Ebenezer Howard at the turn of the century. The development displays Gaudí's innovative design capabilities over an entire landscape, even though the only homes completed were his own house (intended to be the model residence to show to prospective lot buyers) plus one other residence, and like many other Garden City-inspired endeavors outside Britain, the project is basically a financial failure. The park's design is thoroughly integrated into the terrain, with rough-hewn inclined columns seemingly excavated out of the hillsides and covered by vines. Its irregularities and inclined slopes allowed Gaudí to experiment structurally with various ideas that more conventional sites, like flat city lots, did not accommodate.

The centerpiece of the Parc Güell consists of a columned market space supporting an open plaza bounded by a serpentine bench covered with a conglomerate of discarded ceramic tiles, called trencadís, a hallmark of Catalan craftsmanship. The plaza drains into channels within the columns that collect rainwater and flow it into cisterns for reuse by the Parc's intended residents. The market is connected to the Parc's entrance by a grand staircase with a tiled fountain sporting the face of a dragon and the striped Catalan flag. There, the gatehouse and concierge's residence consist of rocky lodges crowned by irregular, conical spires, appearing to be crafted out of gingerbread. The undulating forms, inspired by inverted catenary arches, and brilliantly-colored tilework point to the collaborative nature of Catalan Art Nouveau, involving teams of craftsmen specializing in different media and the reliance on the honest treatment of ecologically-sensitive materials.

Barcelona, Spain

Casa Milà

Nicknamed "La Pedrera," which translates to "open quarry," the Casa Milà, also located on the Passeig de Gracia in central Barcelona not far from the famous "Apple of Discord," is one of the relatively few apartment buildings Gaudí designed. Today it houses the Fundació Catalunya-La Pedrera, which manages exhibitions inside the building and provides tours.

The building's moniker "La Pedrera" is apt, since many of its features speak to the relationship to a quarry. For one, it consists of essentially two ovoid structures that encircle a pair of courtyards, much like the rock is excavated and stripped off the sides of a quarry; and the undulating curves of the building resemble the irregular surface bands that are left on the face of quarries after stone is removed. The balconies are fabricated from twisted, irregular scraps of iron designed by Gaudí's collaborator, Josep María Jujol, recalling the abstraction of natural forms, such as leaves and blades of grass as well as the economy of materials. Its roof is punctuated by groups of chimney pots shaped like knight's helmets and spiral turrets crowned by crosses. Originally, Gaudí designed religious statuary to also occupy the roofline, but anticlerical riots in Barcelona in 1909, known as "Bloody Week" prompted his patron, Pere Milà, to forgo this choice. The building's flamboyance, including its often garish interior colors - some walls are actually lime green - reflects the personality of Milà himself, a wealthy developer known for his ostentatious lifestyle. Likewise the sensuous curves of the exterior skin, which makes the building appear to be in constant motion, reflecting the frenzied pace of activity around the busy intersection fronting it - as if to suggest that the speed of modern life seeps into even the most static aspects of human existence.

Stone, tile, wrought iron - Barcelona

Expiatory Church of the Sagrada Família

The Sagrada Família remains Gaudí's most famous - and most controversial - building. When finished, it will be the tallest, if not one of the largest, churches in the world. The project is an immense undertaking, to which Gaudí was appointed in 1883 (officially in 1884), a year after its conception. It occupied him continuously for the rest of his life, and when he died in 1926, the basilica was only about 20 percent complete (despite Gaudí's exclusive focus in the last twelve years of his life). It is representative of the architect's devout Catholic faith, as Gaudí knew that he would not come close to live to see its completion, but this did not deter him. Once, when questioned about its timeline, he supposedly replied, "My client is not in a hurry."

Paul Goldberger has declared Gaudí's church to be "[t]he most extraordinary personal interpretation of Gothic architecture since the Middle Ages," and indeed the building, like many of Gaudí's other works, can be rightly compared to the timeline, craftsmanship, and formal qualities of the great Gothic cathedrals of the Middle Ages. It may be truly the "last" real Gothic building, as its various facades are covered in didactic sculptural decoration from the life of Christ and it uses a five-aisle Latin cross plan reminiscent of traditional Catholic cathedral architecture. It is not, however, the cathedral church of the Archdiocese of Barcelona.

The Sagrada Família also represents arguably the culmination of Gaudí's parabolic and catenary structural system, evident in numerous other designs, including the unbuilt scheme for the Colònia Güell church outside Barcelona. Not surprisingly, Gaudí's designs only use curved forms - an homage to the conditions of nature, in which, Gaudí declared, "there are no straight lines." Nonetheless, many of Gaudí's ideas for the completion of the church were lost in a fire that destroyed the workshop on the site during the Spanish Civil War in July 1936; subsequently, the project's chief architects have tried to piece together Gaudí's original vision in concert with their own designs for the structure. In some ways this is in keeping with Gaudí's wishes, as most of his works had been collaborative efforts with numerous other craftsmen and designers, and knowing that he would not live to see the church's completion, he envisioned the finished product to be a collaborative inter-generational design.

The church, which has welcomed visitors ever since Gaudí's time, is today about 70% finished, with the last phase of work to be completed consisting of the raising of the six massive central spires, and its structure (minus the exterior decoration and embellishments) is scheduled to take place in 2026. While admired by many, including Louis Sullivan and Walter Gropius, it has had its detractors, including the architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner and the writer George Orwell. Others have called for work to be terminated definitively, citing large expenses (the annual budget for construction runs to 25 million euros), though the construction has always been funded by donors or, more recently, by visitors' entry fees, not by government or church sources. Yet it remains a prized landmark (even well before completion) and one of the most recognizable symbols of Catalonia and Barcelona and likely will for decades to come.

Stone, tile, stained glass, iron - Barcelona, Spain

Biography of Antoni Gaudí

Childhood

Antoni Plàcid Guillem Gaudí i Cornet was born in Reus, Catalonia, south of Barcelona on the Mediterranean coast, in June 1852. His birthplace is the question of a small controversy, as precise documentation is nonexistent and sometimes it is claimed that he was born in the neighboring municipality of Riudoms, his paternal family's native village (though he was baptized the day after his birth in the church of Sant Pere Apòstol in Reus). He was the youngest of five children born to Francesc Gaudí i Serra, a coppersmith, and his wife, Antònia Cornet i Bertran. Gaudí's family had roots in the Auvergne region of southern France.

From the beginning, Gaudí exhibited a great appreciation for nature and especially the environment of his native region of Catalonia. He eventually became a very enthusiastic outdoorsman, joining the club called the Centre Excursionista de Catalunya in 1879 (which took many trips into the countryside of the region and southern France). Despite his zeal for the outdoors, Gaudí was sickly as a youth with various ailments, including rheumatism, which seem to have contributed to his reserved character.

Barcelona and Architectural Education

Gaudí spent most of his time up to the age 16 in Reus, where he attended nursery school with Francesc Berenguer, who would become one of his assistants, and worked in a textile mill. In 1868 he moved to Barcelona to study teaching in a convent. While there he became interested in utopian socialist ideas and together with two of his fellow students he conjured up a plan to transform the Poblet Monastery into a utopian phalanstery, a communal, experimental institution proposed by Charles Fourier and other philosophers of the age.

Gaudí completed four years of compulsory military service starting in 1875, but poor health meant that he spent much of his time on sick leave, which enabled him to enroll at first the Llotja School and then the Barcelona Higher School of Architecture, from which he graduated with a degree in architecture in 1878. Health problems seem to have been pervasive in Gaudí's family at the time, as in 1876 his mother died, as did his older brother Francesc, who, ironically, had just become a physician.

Nonetheless, the young Gaudí quickly developed the rudiments and connections that would propel him to professional success. He became a draftsman for some of Barcelona's most renowned architects; including Joan Martorell, Josep Fontserè, and Leandre Serrallach - employment which helped pay for his studies. During this time Gaudí produced one of the few surviving handwritten documents attributable to him: the so-called "Reus Manuscript," essentially a student diary in which Gaudí recorded his impressions of architecture and interior decor, and setting forth his early ideas on these topics.

Independent Practice

Gaudí began to garner his own clients even before his graduation in 1878. That year, he produced a showcase for the glove manufacturer Camella at the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) in Paris, which caught the attention of the textile manufacturer Eusebi Güell, who immediately asked Gaudí to design the furniture of the pantheon chapel of the Palacio de Sobrellano in Comillas (the structure was being designed by Gaudí's former employer and mentor, Joan Martorell). Eventually Eusebi Güell would commission Gaudí for no fewer than five major projects over the next thirty-five years.

In 1877, Gaudí received his first significant commission, the Casa Vicens, a residence for Manuel Vicens i Montaner, a local brick and tile manufacturer, which effectively established Gaudí's reputation in Barcelona. In 1883, the same year the Casa Vicens was completed, Gaudí began his work on the Sagrada Família in Barcelona.

Through a commission in 1878 for the Workers' Cooperative of Mataró building, Gaudí became attracted to Josefa Moreu, a teacher there, but she apparently did not return his affections. She was the only woman for whom Gaudí ever expressed romantic interest, and thereafter he buried himself in work for the remainder of his life, with his Catholic faith gaining an ever-greater hold over his psyche after the rejection. In 1885, he moved briefly to the rural town of Sant Feliu de Codines in order to escape a cholera epidemic, staying in Francesc Ullar's residence. Grateful for the emergency lodging, Gaudí designed a dinner table in return for the housing.

The 1888 World's Fair brought the spotlight to Barcelona, and the city received major improvements, including the expansion of electric service, which was exhibited prominently at night by arches of lights that spanned the width of the city's major boulevards. Gaudí was awarded the job of designing the pavilion of the Compania Trasatlantica, a shipping company owned by the Marquis of Comillas, which was notable for its use of horseshoe arches and led to a few restoration jobs for Gaudí from the Barcelona city council.

Patronage by the Güell Family

Gaudí received the bulk of his important commissions from Eusebi Güell; the two men had much in common, including their devout Catholic faith. These began in 1884 with the designs for the Güell Pavilions, the outbuildings for Güell's summer house in Pedralbes, Catalonia, and continued with Gaudí's work on the Palau Güell (1886 - 88), the family home in central Barcelona, which is today open to the public for visits. In 1890, Güell moved his factories to the town of Santa Coloma de Cervelló and asked Gaudí to design a community for his workers. Gaudí worked on the project for nearly 30 years before Güell's sons abandoned the project in 1918. Between 1895 and 1897, Gaudí built the Bodegas Güell, a winery and hunting lodge at La Cuadra de Garraf. And in 1900 Gaudí began the large landscape development called the Parc Güell that occupied him until 1914.

Güell was among Gaudí's most prominent friends to describe him amicably, as a pleasant person to talk to, polite, and faithful to his close associates, a contrast with some reports that depict Gaudí as gruff, aloof, and unsociable. Early in his career, Gaudí played the part of a socialite, reputedly dressing in fancy suits and frequently attending events such as the theater, opera, indulging an appetite for gourmet food (apparently, despite his vegetarian diet), and arriving at his job sites in a horse-drawn carriage. This changed dramatically as time passed, as his faith prompted him to lead a far more ascetic lifestyle.

It is worth noting, however, that Gaudí did cultivate a much wider clientele than merely the Güell family; he also designed numerous private houses, apartment blocks, industrial and office buildings, and a large number of church-related commissions, including several restorations. In 1908, Gaudí was even asked by two American entrepreneurs, whose names remain a mystery, to design a skyscraper for New York, called the Hotel Attraction, distinguished by a parabolic central tower intended to be taller than the Empire State Building and topped by a star motif.

Catalan Nationalism

Gaudí was rarely directly involved in political activities, despite his frequent use of Catalan motifs in his buildings, which disclose his deep allegiance to his native region. He maintained close links with regional artist societies, including the Catholic Cercle Artístic de Sant Lluc (Artistic Circle of St. Luke), which he joined in 1899. But he steadfastly refused urgings from associates and friends to run for office, as a few of his fellow Modernisme architects had done. Gaudí did, however, attend demonstrations. He was beaten by police during a riot in Barcelona in 1920, and in September 1924, the National Day of Catalonia, Gaudí was beaten and arrested at a protest against the dictator Primo de Rivera's ban on the use of the Catalan language. He was briefly jailed, then released on 50 pesetas bail.

Last Years and Death

After 1914, Gaudí, whose devotion to his Catholic faith had become nearly his only interest outside of his architectural practice, ceased work on all other projects besides the Sagrada Família, which occupied him until his death in 1926. On June 7 of that year, he was walking from work to his daily prayer and confession at the church of Sant Filip Neri when he was struck by tram on the Gran Via de les Corts Catalanes and lost consciousness. His shabby clothes and lack of identifying documents meant that he was assumed to be a beggar, and medical treatment was delayed almost a day as a result. He was finally identified by the chaplain of the Sagrada Família but his condition had taken a turn for the worse, and he passed on a few days later. Gaudí was given a funeral attended by a very large crowd, and buried in the Sagrada Família's crypt, though the church remained far from completed at his death.

The Legacy of Antoni Gaudí

Gaudí's impact is difficult to quantify. His fame grew - even internationally - during his lifetime, but the appreciation of his work began to fade after his death. During the Spanish Civil War (1936-39), during which the city of Barcelona suffered significantly, as it was the last holdout against Franco's Nationalist forces, the workshop at the Sagrada Família was burned, and many of Gaudí's extant drawings and famed models (his preferred working method of design) were lost. Work stopped for a time on the Sagrada Família, and well into the 1990s the question has been raised as to whether work on the structure should stop altogether.

The rise of the International Style, particularly in the 1940s and '50s, did much to turn public opinion against Art Nouveau, and Gaudí's highly unusual works were often derided as fantastical and in some cases backwards. As late as 1993, the architectural historian Neil Levine characterized the gatehouses to the Parc Güell as something that gnomes would jump out from to frighten passing visitors.

The appreciation of Gaudí's work has only magnified, however, since 1960, with the writings of scholars such as George Collins, Judith Rohrer, Ignaci de Sola-Morales, and Gaudí's students, including Cèsar Martinell, and others that have helped bring Gaudí and Catalan Modernisme even greater international renown. Gaudí is respected today as an innovator in many ways. Though long described as an Art Nouveau architect, most recent appraisals have emphasized his singular genius amongst his Catalan and European contemporaries.

Though well aware of the rich and varied architectural past in Catalonia due to its Mediterranean location, Gaudí did not remain a revivalist. He was more daring with his experiments in parabolic structures that he studied using models in his workshop. These forms, combined with a richness of the decorative surfaces and materials common to many Catalan structures, mean that his buildings will continue to attract notice well into the future.

Today Gaudí's global fame as a designer is assured, and seven of his buildings in Barcelona are listed by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites. Numerous tributes to Gaudí include his beatification by the Catholic Church in 2000; Christopher Rouse's guitar concerto Gaudí (1999), a musical of the same title from 2002, the Gaudí awards by the Catalan Film Academy, and an Iberia Airbus A340 jet named after him. Perhaps most significant is the anticipated completion of the church of the Sagrada Família (now projected for 2026) on the centenary of Gaudí's death; such an event should bring the career of this legendary architect to an appropriate and dramatic conclusion.

Influences and Connections

-

![Victor Horta]() Victor Horta

Victor Horta -

![Hector Guimard]() Hector Guimard

Hector Guimard - Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc

- Joan Martorell

- Josep Fontserè

- Eusebi Güell

- Josep María Jujol

- Leandre Serrallach

- Francisco de Paula del Villar i Lozano

- Emili Sala Cortés

- Llorenç Matamala

- Josep Francesc Ràfols

- Joan Bergós

- Cèsar Martinell

- Joan Rubió

- Pere Santaló

- Joan Maragall

- Jacint Verdaguer

- Joan Llimona

- Francesc Berenguer

-

![Art Nouveau]() Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau -

![Art Deco]() Art Deco

Art Deco ![Modern Architecture]() Modern Architecture

Modern Architecture

Useful Resources on Antoni Gaudí

- Gaudí, the Life of a VisionaryBy Juan Castellar-Gassol

- Antonio GaudíBy George Collins

- Gaudí: His Life, His Theories, His WorkBy Cèsar Martinell

- Gaudí: A BiographyOur PickBy Gijs van Hensbergen