Summary of Symbolism

As opposed to Impressionism, in which the emphasis was on the reality of the created paint surface itself, Symbolism was both an artistic and a literary movement that suggested ideas through symbols and emphasized the meaning behind the forms, lines, shapes, and colors. The works of some of its proponents exemplify the ending of the tradition of representational art coming from Classical times. Symbolism can also be seen as being at the forefront of modernism, in that it developed new and often abstract means to express psychological truth and the idea that behind the physical world lay a spiritual reality. Symbolists could take the ineffable, such as dreams and visions, and give it form.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- What unites the various artists and styles associated with Symbolism is the emphasis on emotions, feelings, ideas, and subjectivity rather than realism. Their works are personal and express their own ideologies, particularly the belief in the artist's power to reveal truth.

- In terms of specific subject matter, the Symbolists combined religious mysticism, the perverse, the erotic, and the decadent. Symbolist subject matter is typically characterized by an interest in the occult, the morbid, the dream world, melancholy, evil, and death.

- Instead of the one-to-one, direct-relationship symbolism found in earlier forms of mainstream iconography, the Symbolist artists aimed more for nuance and suggestion in the personal, half-stated, and obscure references called for by their literary and musical counterparts.

- Symbolism provided a transition from Romanticism in the early part of the 19th century to modernism in the early part of the 20th century. In addition, the internationalism of Symbolism challenges the commonly held historical trajectory of modern art developed in France from Impressionism through Cubism.

Overview of Symbolism

Saying, "I paint ideas, not things," George Frederick Watts became a leading Symbolist. He said his allegorical Hope (1886) was meant, "to suggest great thoughts which will speak to the imagination and the heart."

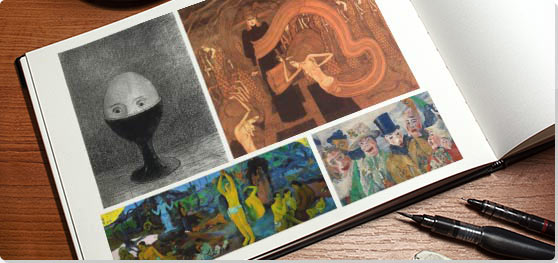

Artworks and Artists of Symbolism

Jupiter and Semele

This painting illustrates the myth that tells of the love between Jupiter, the divine king of the gods, and Semele (the embodiment of that which is earthly), who upon the suggestion of Jupiter's wife Juno, asks Jupiter to make love to her in his divine radiance. Jupiter cannot resist the temptation of her beauty, with the acknowledgment that she will be consumed by his light and the fire of his divinity (he is crowned with thunderbolts). Thus the painting is symbolic of humanity's union with the divine that ends in death. However, as the artist wrote, "all is transformed, purified, idealized. Immortality begins, the Divine pervades everything." Themes of death, corruption, and resurrection all make their appearance. As in this painting, Moreau followed the example of Wagner's music, composing pictures in the style of symphonic poems in their richness of detail and color, although that same characteristic prevented him from emphasizing the more modern aspects of Symbolism. The artist expressed himself in a more traditional style, but true to Symbolism, meaning evolves from the forms themselves; humanity is small-scaled and vulnerable in its fleshy voluptuousness. The androgynous figure of Jupiter suggests the isolation of the dreaming artist and the life of ideas. Moreau, central to any discussion of Symbolism, contributed to the more literary aspects of Symbolism, choosing his subjects from the Bible or, as here, mythology - at the same time that he was able to point out some of the neuroses of the modern age.

Oil on canvas - Gustave Moeau Museum, Paris

The Eye Like a Strange Balloon Mounts Toward Infinity

Although Edgar Allan Poe had been dead for 33 years at the time of Redon's lithograph and both Charles Baudelaire and Stéphane Mallarmé had translated his writings between 1852 and 1872, this is not an illustrated narrative of Poe's work; instead, it is parallel to it in its evocation of the macabre world of the writer. The single eye - the all-seeing eye of God - is an old symbol, but is here transformed. The large scale of the eye is the symbol of the spirit rising up out of the dead matter of the swamp. It is a physical organ that looks upward toward the divine, taking with it the dead skull. The aura of light surrounding the main image helps express the idea of the supernatural, as does the nebulous space. The work evokes a sense of mystery within a dream world. However, Redon's works should not be confused with Surrealism, for they are meant to create a coherent, specific idea - the head as the origin of the imagination and the spirit lodged in matter.

Also, Redon's works distinguish themselves from Surrealism in that the vision is possible to construct. Redon creates ethereal, macabre visions, but they are essentially realistic visions. As the artist himself wrote, "I approached the unlikely by means of the unlikely and could give visual logic to the imaginary elements which I perceived." Redon was, more than some Symbolists, more of a modernist. Although a Symbolist, he was also interested in the scientific materialism of the time - in Charles Darwin's work on evolution, in the study of zoological forms, and, as evidenced in this work, in the technology of the hot air balloons that were popular at the time. His work was a manifestation of his own private world expressed in personal symbols - thus more open to interpretation - and allowed the viewer to understand what hidden realities lay within the forms.

Lithograph - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Death and the Masks

Ensor imparts lifelike qualities to the skull of Death in the center, with its chilling grin, and to the masks of the people; the mask becomes the face, and yet it is still a mask that tries to cover up the spiritual hollowness of the bourgeoisie and the decadence of the times. The crowded composition suggests that this is a pervasive problem and that the painting is the artist's critique of contemporary society. Ensor had an interest in masks because his mother owned a souvenir shop selling such articles as these papier mache masks worn at carnival time in Belgium. Ensor desired a return to the "pure and natural" local carnivals and festivals of his native Belgium with a view toward creating cultural unity, but realized that tourism, commercialization, and industrialization would prevent that from happening.

Moreover, Ensor was heir to the whole Northern tradition of caricature, the grotesque, and fantasy, as seen in the work of Hieronymus Bosch and even Pieter Bruegel. But as opposed to the naturalistic underpinnings of the work of Bosch and Bruegel, Ensor works with a light, bright palette that suggests whimsy and absurdity at the same time that he employs a rough and textural application of paint, which signals the depth and horror of the malaise of the times. Thus, Ensor's contribution to Symbolism was that before the Expressionists of the early-20th century, he called upon raw color and savage texture to strip down to the layers of the human psyche, plumbing its depths -- in addition to supplementing his Symbolic vocabulary with subtle political overtones.

Oil on canvas - Musée royal des beaux-arts de Liège

The Three Brides

These emaciated figures with spindly arms and emphatic gestures derive from Javanese puppet theatres (Toorop was a Dutch artist who was born in Java). The artist sets up an allegory of the three states of the soul, consisting of the bride dedicated to Christ, the bride dedicated to earthly love, and the satanic bride who appears to be Egyptian - adorned with a necklace of small skulls and grasping a small snake. The group is surrounded by handmaidens and some additional obvious symbols: lilies, roses, and a bowl of blood symbolizing the purity of the Passion. The bed of thorns denotes the pains of existence. The bells hang from a nailed figure, and the flowing rhythms are symbolic of the sound of bells, with the artist attempting to depict another one of the senses. These linear rhythms proliferating in the background derive from the field of English book illustration. The whole effect is pale and monochrome.

The artist's goal was to relate humans to the spiritual world, specifically identifying women as the source of evil - an idea found in the work of many writers and artists of the time. Sin was associated with sex, and sex was related to procreation and death, with woman as the ultimate source of death. Thus Toorop provides decipherable iconography, but with Symbolism's characteristic inner vision. His is the mystical equivalent of Munch's more sensuous and expressive version of much the same subject. However, Toorop's Symbolism was unique in combining meaning-laden shapes and colors with specifically non-Western sources.

Drawing (Black chalk, tinted) - Kröller Müller Museum, Otterlo

The Dance of Life

Munch presents the three stages of woman (all portraits of his lover Tulla Larsen): the virgin symbolized by white, the carnal woman of experience in red, and the aged, satanic woman in black. The sea is the beyond, eternity, the edge of life into the vast unknown, and finally, death. The dance is therefore the playing out of earthly life and the life of the senses before death, and for the time being, at least, keeps death at bay. In the background a lone, female figure stands in front of the Freudian male phallic symbol of the setting sun's reflection. Multiple male figures hover about another female figure in white (or perhaps the same one at a different moment). In the right middle ground, a male figure grabs lustily at his partner who leans away from him. This male figure has been identified as a caricature of the playwright Gunnar Heiberg, who had introduced Munch to Larsen and of whom he was jealous. In the foreground a couple - Larsen and Munch, himself - is physically proximate, in fact symbolically entwined through the shapes of the lower parts of their bodies. Their faces, however, indicate their separation from each other. The figures seem locked in the composition despite the fact that they are supposed to be participating in the movement of a dance. Munch was influenced by the pessimistic and fatalistic philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer. Indeed, the couple's fate is sealed: they never married, nor did they procreate. The Dance of Life is thus also a dance of death. In this, as well as his other works, Munch was amongst the first to iterate, and through such direct means, the modern theme of alienation and isolation that fascinated so many writers and artists of the ensuing century.

Oil on canvas - National Gallery, Oslo

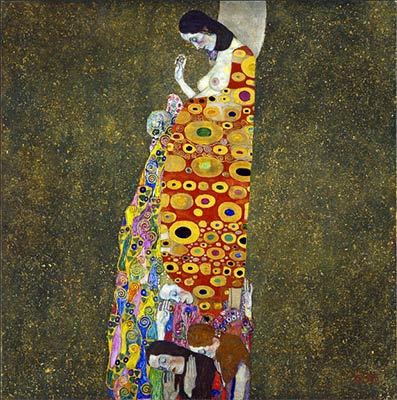

Death and Life

In this updating of the 17th-century theme of vanitas (the vanity of earthly life), Death stares across the negative space as Life reveals itself in the figures who come into being, exist, and pass out of existence; they are born, live, and die as part of the great stream of life. This painting takes part in the fashionable pessimism of the age, which identified a cosmos driven by sexual (as opposed to sinful) urges, part of a blind drive to procreate. But there is in this painting also an emphasis on the voluptuous in both the modeling of the figures and richness of the patterns. In regard to these patterns, Klimt had been influenced by Japanese art, Minoan art, and the Byzantine mosaics he had seen at Ravenna. There is tension between the flat, elegant, glittering pattern and the more academic treatment of the bodies - between abstraction and representation. The decorative schema locks the figures in place and counteracts their existence as physical beings. Rather, they serve as symbols for states of being. It has been pointed out that Klimt offers a note of hope; instead of feeling threatened by the figure of death, his human beings seem to disregard it. Klimt himself was approaching death, and perhaps the passive quality of this work is emblematic of his being resigned to that fact. The painting also reflects the time and ideas of Sigmund Freud who was also from Vienna, and who identified the main motivating actors of the human psyche to be eros (the sexual instinct for the purpose of the continuation of life) and thanatos (the death instinct for the purpose of ending the anxieties of life). Thus, not only did Klimt help advance Symbolism from its more traditional style, as evidenced in the work of Moreau, but he also pushed the boundaries of subject matter by incorporating such controversial and avant-garde themes as were circulating in the work of Freud.

Oil on canvas - Leopold Museum, Vienna

Beginnings of Symbolism

Symbolism grew out of and was codified in the works of the writers Gustave Kahn and Jean Moréas, who first used the term "Symbolism" in 1886. These writers rejected Émile Zola's Naturalism and favored the subjectivity of the poets Stéphane Mallarmé and Paul Verlaine, who both exercised great influence. Mallarmé hosted Symbolist receptions every Tuesday in his apartment; he was friends with many Symbolist artists including Paul Gauguin, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Odilon Redon, and Edvard Munch.

Symbolism followed Impressionism chronologically, but it was the antithesis of it, as the emphasis was on the meaning behind the shapes and colors. It did, however, echo the sentiments of the Post-Impressionists Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin who both lamented the spiritual decline of the modern world. Elements of Symbolism appeared in their works, but the mainstream Symbolists showed greater concern for the interior life rather than external reality. Symbolism in the visual arts had its sources in early-19th-century Romanticism's emphasis on the imagination, rather than reason, and the themes first evident in the poet Charles Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du Mal (1857). Additional sources include the personal visions of painter and poet William Blake, the aestheticism of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in England, and the poetic, allegorical, moody dream worlds created by Edward Burne-Jones, Dante Gabriel Rosetti, and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes.

Symbolism was in many ways a reaction against the moralism, rationalism, and materialism of the 1880s. This fin-de-siècle period was a period of malaise - a sickness of dissatisfaction. Artists felt a need to go beyond naturalism in art, and like other forms of art and entertainment at the time, such as ballet and the cabaret, Symbolism served as a means of escape.

Symbolist Theory and Albert Aurier

An offshoot of the literary Symbolism that influenced visual art was the field of art criticism, particularly that of Albert Aurier. In 1891 he wrote, in what became essentially a Symbolist manifesto, that art should be

1) Idéiste (Ideative) ... expressing an idea

2) Symbolist since it expresses that idea through form

3) Synthetic since it expresses those forms and signs in a way that is generally understandable

4) Subjective since the object ... is only an indication of an idea perceived by the subject

5) and as a result it will also be Decorative ... since decorative painting is at once an art that is synthetic, symbolist, and ideative.

Symbolism: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

The period in which the Symbolists worked was marked by confusion regarding moral, social, religious, and intellectual attitudes. The world was expanding beyond European norms; socialism no longer consisted of the benevolent intentions with which it set out. The relationship between love and marriage was being questioned, as was religion. Artists in particular felt that they were isolated and separate from the bourgeoisie. Yet the idea of the spiritual was very important in the development of Symbolism and reflected the anti-materialist philosophies that were concerned with mysticism (a direct connection and unity with the ultimate reality). An interest in the occult was related to this concept, as was a taste for the morbid and perverse, as this period is often described as one of "decadence" (a period of artistic or moral decline as seen in the preference for the artificial over the natural - and by extension, the idea that even humanity was in decline). English writer Oscar Wilde's works and the French writer Joris-Karl Huysman's À Rebours (Against Nature) (1884), as well as the art of many of the Symbolists, reflect this decadence.

The Symbolist artists (and writers) emphasized the idea of art for art's sake in that they were, for the most part, against the utilitarian applications for art (that is, different from the Art Nouveau artists) and also believed that art did not have to relate to everyday experience.

Symbolism and Synthetism

Synthetism, in particular, is necessary for an understanding of Symbolist aesthetics. Artists that practiced Synthetism combined elements from the real world or borrowed from other works of art or forms of art to create new realities. For example, among the tendencies of the Symbolists was the interest in assimilating music into art; this idea was influenced by the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer who conceived of music as an art form that communicated its meaning directly. The visual artists emulated this characteristic of music. They also used musical methods of organizing compositions, such as the use of leitmotifs - repeating elements that unify the work. Symbolist artists were particularly interested in the music of Richard Wagner, who believed in the spiritual forces in music and envisioned a sweeping unification of the arts. Thus, whether visual or audial, the Symbolists attempted to put inarticulate experience into some kind of apprehensible sensory form.

Symbolism and Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau is considered a subspecies of Symbolism. There is a great deal of overlap in Art Nouveau and Symbolist subject matter (for instance in the decadent themes of the work of Aubrey Beardsley), but Art Nouveau is much more specifically an ornamental style based on organic form and applied to all forms of art, that is, to any object that can be made "artistic," e.g. jewelry, furniture, etc. It is difficult to trace its origin, but most scholars agree that it began in Belgium with the work of Victor Horta. However, the style quickly became international. Art Nouveau's purpose was to create an aesthetic that could be applied to all art forms and therefore could exist in harmony with the needs of the machine age and the modern world.

International Aspects of Symbolism

Most scholars refer to Symbolism in the visual arts as an attitude toward subject matter rather than a movement, as it was more clearly in literature. Most late-19th-century Symbolist artists experienced the sociopolitical and moral upheaval that was prevalent at the time, resulting in personal, spiritual, mystical, and oftentimes obscure symbols and subjects relating to the perceived decadence of the period. The works of artists from many countries shared in this vision to varying degrees and arising from various visual sources. We begin with France, where the term 'Symbolism' was first used to describe this phenomenon, and where the aesthetic was first codified.

Symbolism in France

The two most notable Symbolist artists in France were Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon. Moreau looked toward the Romantic artists such as Eugène Delacroix and the exotic in general. Redon was also influenced by the Romantics in his creation of fantasy dream worlds, but also by Francisco Goya, which accounts for the disquieting effect of his work.

The Nabis

The Nabis (from the Hebrew and Arabic term for "prophets," and by extension, the artist as the "seer") were a Symbolist group founded by Paul Sérusier in 1889 and based on his 1888 painting The Talisman. Although they did not ascribe to the same religious or political views as other Symbolists, the Nabis wanted to be in touch with a higher power; they believed that the artist had the role of a high priest who has the power to reveal the invisible. Their style grew more out of the work of Paul Gauguin, manifested in flatness and stylization, although the subject matter is different, focusing on domestic interiors, as in the case of Édouard Vuillard and Pierre Bonnard. Many of the Nabis artists published in the Symbolist review La Revue Blanche alongside their literary counterparts.

Symbolism and Rosicrucianism

The Rosicrucians were a group of artists headed by the writer Sar Joséphin Péladan, who followed the occult beliefs of the supposed 15th-century visionary Christian Rosenkreuz. They rejected the materialism of the age, and they revived Catholic and Renaissance art, but with mystical, occult overtones. Art for this group was an initiation into religious revelation. The works they produced took the form of mystical allegories, but were stylistically more traditional. The artists Charles Filiger, Armand Point, and Marcellin Desboutin were associated with this Symbolist group, and exhibited in the Paris Salons of the Rose and Croix from 1892 until 1897. These salons were significant in that they highlighted the work of a number of artists from countries other than France.

Symbolism in Belgium

In Belgium, the two most significant artists were Fernand Khnopff, in whose work a certain level of perversity persists, and the more idiosyncratic and less literary James Ensor, who investigated the symbolism of masks.

Symbolism in England

Symbolism in England in the 1890s can be seen in the work of the artist Aubrey Beardsley and the writer Oscar Wilde, which might be described as "decadent," with an emphasis on the erotic. Beardsley explored such Symbolist themes as the medieval dream world of King Arthur, the idea of the femme fatale, the thematic material of the composer Richard Wagner, and dandyism. Beardsley's style, however, with its elastic lines, is closer to that of Art Nouveau, with which he is also associated.

Symbolism in Other Countries

In Switzerland, Arnold Böcklin created his "mood landscapes," synthesizing the images from his imagination. His countryman Ferdinand Hodler produced works, such as his Night (1896) and Day (1899), which are characterized by more illusionistic and modeled figures as well as the use of personifications and allegories, rather than symbols as such - although the postures and gestures of his figures do seem to symbolize states of being. In Italy, Giovanni Segantini created mystical visions of the Swiss Alps. An important, if short-lived, group of Symbolist artists came from Holland, including Jan Toorop and Johan Thorn Prikker, who both created archetypal Symbolist pictures. Russian Symbolist artists, such as Leon Bakst, contributed designs for the stage. Examples from the United States included Arthur B. Davies and Maurice Prendergast, who only partially shared in any Symbolist vision, turning as well to other styles, and Alfred Pinkham Ryder, who, although he painted mystic, moody allegories, is usually considered an idiosyncratic artist, not associated with any particular group.

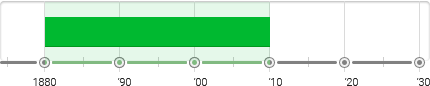

Later Developments - After Symbolism

Later Symbolist painting is best exemplified in the works of Gustav Klimt and Edvard Munch. The former's work represents more of a culmination of art prior to the effects of World War I, while the latter's work was and continued to be considered modern throughout his career.

The Symbolism of Gustav Klimt

In Austria, Symbolism is best represented by the work of Gustav Klimt (who was also associated with Art Nouveau), the progressive artist who entered the international Symbolist arena in 1897 by founding the Viennese Secession group. This move entailed a rejection of the salon system and other academic organizations in order to further the modern, more abstract direction, which also entailed more controversial content that mirrored Freud's recent findings. In fact, many historians have commented upon the rapid internationalization of the Art Nouveau style as helping to supplant that of the Symbolists. In view of the eclecticism of his multiple sources, his work has been described as the "last fruits of the Symbolist harvest." His contribution to Symbolism was that many of his works, though Symbolist in subject matter, aimed to unite the arts and crafts in a way similar to that of the Art Nouveau aesthetic, but different from the other Symbolist artists who were more interested in "art for art's sake."

Symbolism of Edvard Munch

The Berlin Secession in Germany was more conservative than that of Austria, although it did mount an exhibition of the more avant-garde work of the painter from Norway Edvard Munch. Unlike many of the other Symbolists, Munch remained a prolific, modern, and influential painter throughout his life. As one critic has written regarding Munch's work: "long before it was enunciated elsewhere, he embodied the doctrine that the modern artist puts himself personally at risk in his art - that in giving life to his creations, he necessarily risks his own." Munch's work is Symbolist in that the meanings are derived from the colors and forms; his work goes beyond that of other Symbolists in that it is more formally expressive and uses figures' postures and gestures to consistently produce new meanings.

Late Manifestations of Symbolism

Later Symbolist ideas appear in the work of Expressionist artist Oskar Kokoschka in works such as The Bride of the Wind (1914), where he draws upon the well-worn symbol of two lovers in a boat. Even the young Pablo Picasso during his Blue and Rose Periods is essentially a Symbolist, when he seizes upon Symbolist subjects such as the clown as a symbol of the outsider.

However, in the years leading up to World War I, there was growing dissatisfaction with the over-refinement and obscurities of Symbolism, as many artists desired to move in the direction of the raw and "primitive," in the hopes of bringing a new world into being - even if war was part of the answer.