It represents, in mechanics, the greatest efficiency.

We use the words "greatest efficiency" in the precise sense - as they would be used in a text book of MECHANICS."

Summary of Vorticism

Vorticism blasted onto the London art scene, becoming England's first radical avant-garde group. Embracing contradiction, humor, and ostentatious rhetoric, the Vorticists celebrated the energy and dynamism of the modern machine age and declared an assault on staid British traditions in order to inaugurate a new era where art belonged to all. Rebelling against the genteel semi-abstractions then fashionable among the London bourgeoisie and championed by critics Roger Fry and Clive Bell, the Vorticists developed an abstract style with bold colors, harsh lines, and sharp angles to depict the movement of industrial life. Vorticism encompassed many media, including painting, sculpture, literature, typography, and design in an effort to transform how people interacted with the world. The horrors of World War I, however, dampened their idealization of the machine and dissipated the momentous energy of the group.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- When poet Ezra Pound named the group, he employed the image of the vortex to describe the creative energy brewing around this group of artists. The artists then elaborated on this metaphor of the vortex to animate much of their aesthetic theory. As Wyndham Lewis explained, "You think at once of a whirlpool. At the heart of the whirlpool is a great silent place where all the energy is concentrated; and there at the point of concentration is the Vorticist." The vortex was also the site of artistic creation. Vorticist compositions rely heavily on diagonals that seem to splinter apart and yet remain solidly contained on the picture plane.

- Embracing the possibilities of the machine's energy, Vorticism drew on the fragmentation of Cubist composition and the movement championed by the Italian Futurists to develop a style of pared down geometry that evoked both dynamism and a still center.

- The Vorticists embraced the machine with all of its productive and destructive possibilities. They abstracted machine-age imagery in their compositions and used clean lines and bright colors to further suggest the hard edges and shiny surfaces of the machine. The horror and destruction of World War I caused many of the Vorticists to reformulate the understanding of the place of the machine in modern life, thus largely ending the movement.

Artworks and Artists of Vorticism

In the Station of the Metro

This tiny poem by Ezra Pound contains only one "image." While the poem is usually associated with Pound's Imagist era, in which he strove to a precise clarity without extraneous verbiage, Pound discussed the poem extensively in his 1914 essay on Vorticism. Here he elaborated on the relationship between Vorticist poetry and visual art:

"In a poem of this sort one is trying to record the precise instant when a thing outward and objective transforms itself, or darts into a thing inward and subjective. [...]I realized quite vividly that if I were a painter, or if I had, often, that kind of emotion, or even if I had the energy to get paints and brushes and keep at it, I might [have] found a new school of painting, of "non-representative" painting, a painting that would speak only by arrangements in color."

This "new school of painting" is a reference to the Vorticist movement, which tended to abstraction and emphasized the use of form and color. Pound's short poem similarly emphasizes the careful arrangement of words to create a pared-back but highly vivid effect. It gives an impression of a moment of stillness in a whirl of motion in the busy Metro, recalling the Vorticist search for the static center of the moving vortex of life.

Poem

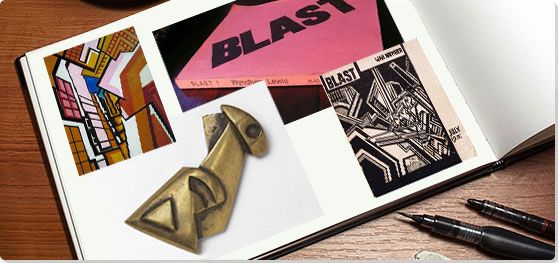

Torso in Metal from 'The Rock Drill'

Epstein's Torso in Metal from 'The Rock Drill' was born of the destruction wreaked by the First World War. In 1913, Epstein created a plaster cast of an abstracted human body - angular and hard - with an embryonic form in its abdomen and placed it astride an industrial mining drill. The result was a towering, menacing figure with great phallic power. It presented an image of the future of humanity as cyborgs, a celebration of the merging of man and machine, a vision of the frightening yet exciting possibilities made possible by the machine age.

As the devastating results of machine warfare in WWI became clear, however, Epstein's outlook on the future of humans and machines changed (in a way that was typical of many members of the Vorticist movement). As Epstein himself later put it in his autobiography: "I made and mounted a machine-like robot, visored, menacing, and carrying within itself its progeny, protectively ensconced. Here is the armed, sinister figure of today and tomorrow. No humanity, only the terrible Frankenstein's monster we have made ourselves into...."

In response to his experience in the war, Epstein removed the figure from the drill and pared it in half, removing most of its limbs. He then cast it in bronze, and presented it on a plinth. Curator Chris Stephens suggests that Epstein "took an expression of masculine aggression and then emasculated it." Although war and the advent of the machine age promoted an aggressive masculine agenda, the result was mutilation and emasculation (through the loss and injury of a generation of young men). Epstein transformed the sculptural figure from an active perpetrator of penetrative violence to a victim of the violence it previously promoted.

Bronze - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Red Stone Dancer

Red Stone Dancer, one of Gaudier-Brzeska's most important works, encapsulates his ideas of pure form and Vorticist dynamism. Gaudier-Brzeska abstracts the body of a dancer into broad planes and organizes them in such a way that they seem to twist around each other. The figure appears to be in mid-movement, suggesting continual motion despite the solid feel of the stone. In a 1912 letter, the artist explained, "Movement is the translation of life, and if art depicts life, movement should come into art, since we are only aware of life because it moves."

The sculpture shows evidence of the artist's interest in the sculpture of African and South American cultures that he saw in the British Museum as well as his interest in Constantine Brancusi's abstract sculptures. Inspired by these examples, Gaudier-Brzeska developed a technique of Direct Carving that he felt was expressive of the contemporary age.

Ezra Pound, with whom Gaudier-Brzeska worked on a theory of Vorticist sculpture, claimed that the Red Stone Dancer was "almost a thesis of his ideas upon the use of pure form." In July 1913, Pound and Gaudier-Brzeska joined a circle of anarcho-individualists, and as art historian Mark Antliff notes brings a radical political orientation to Vorticism. Anliff argues that "central to Gaudier and Pound's vision of Vorticist sculpture was the metaphoric association of Direct Carving with the anarchist politics of direct action."

Red Mansfield stone - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

The Mud Bath

David Bomberg avoided labels and did not sign the manifesto printed in the first issue of BLAST, but he had close ties to the Vorticist group and was invited to exhibit with them in their 1915 exhibition. His most accomplished works are the most Vorticist ones he produced, including his masterpiece The Mud Bath.

Bomberg lived in East London and frequented the public steam baths used by the local Jewish residents. The baths provided a space both for physical as well as spiritual cleansing. Bomberg reduced the human figures he saw in the baths to flat planes and angles, presenting a mass of them against a red field. While the figures appear geometric, even mechanical, they can also be seen to represent the essential core of humanity. The work takes on a graver significance in the wake of the First World War. The reference to "mud" seems to predict the battlefields of World War I, and the viewer is tempted to draw out a play on words between "mud bath" and "blood bath."

The composition is highly geometric and color plays an important role. White and blue shapes are placed against a red ground and offset by a vertical brown column. Human figures are only barely recognizable; it is their movement and interaction that is emphasized, following the Vorticist's desire to present an essential form of humanity through its association with the mechanistic and futuristic.

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Workshop

As the founder of Vorticism, Wyndham Lewis was fundamental to the development of the ideas that characterized the movement; however, he produced less visual artwork than might be expected, dedicating much of his early career to writing and engaging with other members of the literary and artistic scene in pre-WWI London.

The Workshop demonstrates the clarity of Lewis' vision of Vorticism. Bold lines and bright colors create a jostled composition of planes. The title suggests that the painting represents a physical space, but whether it is an interior or exterior space is difficult to discern. It could be a cityscape, perhaps industrial London, or the interior of a studio, with the sky seen through a skylight. The sharp angles and clashing colors are an assault on traditional composition. As Lewis declared in the first issue of BLAST, "even if painting remains intact, it will contain all the elements of discord and ugliness consequent on the attack on traditional harmony."

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Dance

Helen Saunders was a key founding member of the Vorticists; she signed their original manifesto in the first issue of BLAST and a significant number of her artworks and writings were featured in the publication. She is often forgotten, partly because of Wyndham Lewis' male-centric (and ego-centric) view of the movement. She in fact had made a name for herself before she became part of the Vorticist movement, exhibiting in London and Paris from 1912 onwards, and was mentioned in important reviews by critics such as Clive Bell and Roger Fry.

Sadly, no oil paintings by Saunders survive; according to one source, Saunders' sister used one of the artist's oil paintings to cover her pantry floor until the work disintegrated. Of her watercolor works, curator Chris Stephens has said, "Like Lewis' paintings, they have a very strong diagonal dimension, but they also have this sense of uncoiling movement - like a flower opening - which gives them a powerful dynamism. You can usually discern figurative roots to them. When you look closely you can see the suggestion of arms, legs, heads, and figures."

Many critics have dismissed Saunders' work as copying Lewis'. There is a clear similarity, and Saunders collaborated with Lewis and also acted as his secretary when he was away at the front, perhaps saving his life by arranging a hospital bed for him when he returned wounded. However, a piece such as Dance suggests that Saunders' work is significant in its own right, showing a deftness of line and an innovative approach to the idea of the "vortex" through, what Chris Stephens describes, as an "uncoiling movement" present in her imagery.

Graphite and gouache on woven paper - Collection of the David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago

Abstract Composition

Like Helen Saunders, Jessica Dismorr, although little-known now, was well regarded before becoming associated with the Vorticist movement, exhibiting in London and Paris with the Scottish Fauves. Abstract Composition is one of two surviving Vorticist paintings by Dismorr. It has been suggested that some of her other Vorticist works were destroyed after her suicide in 1939, as they were thought to show elements of insanity (she suffered a nervous breakdown after the First World War).

In this work, a number of geometric shapes in pastel colors are set against a black background. The shapes suggest architectural forms that overlap and appear to float past each other. In her contribution to the second issue of BLAST, Dismorr described London's architecture as "towers of scaffolding draw their criss-cross pattern of bars upon the sky, a monstrous tartan."

While rumored to have had an affair with Wyndham Lewis, Dismorr had relationships with both men and women. The historian Miranda Hickman suggests that Vorticism's appeal for Dismorr lay in the fact that it offered "the free navigation of such city spaces, at this time marked masculine [...] through the gestures, perspectives and qualities associated with its masculinity." Hickman goes on to argue that, for Dismorr, Vorticism offered an antidote to the "effects of 'prettiness' that suggested feminine weakness and inferior artistry."

Oil on wood - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Beginnings of Vorticism

Formed and named in 1914, the Vorticist group desired to unsettle England's Victorian attitudes toward art. Painter and author Wyndham Lewis founded the movement of artists and writers in an attempt to represent the energy and vitality of the modern era with what he described as "a new living abstraction." While Vorticism has been called the British version of the Italian Futurist movement, which shared similar influences, Lewis and poet Ezra Pound, who coined the name Vorticism, rejected this correlation.

Lewis himself was, by most accounts, an iconoclast and a visionary, but also a deeply unpleasant person. The modernist author Ernest Hemingway described Lewis as having the eyes "of an unsuccessful rapist." While he later recanted his earlier views, Lewis' reputation suffered due to his antisemitism, Fascist leanings, and his favorable biography of Adolph Hitler, which he wrote in 1931. Despite Lewis' personality and politics, it was partly due to his forceful personality and his aggressive language and opinions that the Vorticist movement came to be Britain's first avant-garde initiative.

The Rebel Centre

For a few months in 1913, Wyndham Lewis worked at Omega Workshops, a collective design firm backed by Bloomsbury painter and critic Roger Fry. Fry attempted to erase the line between fine and decorative arts by hiring innovative artists to design furniture, textiles, and other objects for the modern home. The collective nature of the enterprise meant that artists did not individually sign their work, but instead the objects were stamped with the Greek letter omega. While Lewis welcomed the opportunity to sell objects directly to the public without a middle man, he felt Fry had misled him about a particular commission for an interior design, and in a very public move, Lewis dramatically left the company along with artists Edward Wadsworth, Cuthbert Hamilton, and Frederick Etchells. After leaving, the four artists signed an open letter accusing Fry of deception and dishonesty.

Soon afterwards, Lewis set up a workshop of his own as a pointed alternative to Fry's company. He called it the "Rebel Art Centre." Intended to host exhibitions, lectures, and classes, the Rebel Art Centre soon attracted a group of artists who would be the creative minds behind Vorticism.

Significantly, and unlike many early-20th-century avant-garde groups, several women made up the early roster of the movement despite Futurist artist C.R.W. Nevinson's desire to exclude them. Nevinson reportedly told Lewis, "Let's not have any of those damned women." Certainly, until recently art history has generally ignored the role of women in the formation of the Vorticist movement, but it is notable that the Rebel Art Centre was made possible by Lewis' girlfriend Kate Lechmere, who paid the rent, provided the soft furnishings and lent Lewis money for the first publication of the Vorticist magazine BLAST. Nevinson's attitudes towards women didn't seem to bother Wyndham Lewis, but Nevinson quickly lost favor when he and the Italian Futurist F. T. Marinetti co-authored a manifesto of English Futurism and signed the address of the Rebel Art Centre at the bottom without asking Lewis first.

BLAST! Issue 1 - A Manifesto

Arguably Vorticism's most significant contribution to art history came in the form of its magazine BLAST. Only two issues were published, but they are vital for understanding the Vorticists' aims and positioning and contain some of the most significant works of Vorticist art and poetry.

Wyndham Lewis edited the magazine and intended it to be a radical assault, visually and conceptually, on the British cultural establishment. The front cover proclaims this bold aim with the word "BLAST" written across a bright pink page. Ezra Pound described it as a "great MAGENTA cover'd opusculus".

The first issue, released only weeks before the outbreak of World War I, contained the Vorticists' manifesto, largely composed by Lewis with the help of Pound, written in various sized fonts underlined and bolded across some twenty pages. Largely a list that condemns, or "blasts," and praises, or "blesses," things, ideas, and people, the manifesto combines seriousness, humor, and satire to skewer traditional British art, mores, and politics. Rejecting British penchants for class snobbery, politeness, standardization, and romanticism, Vorticism embraces innovation, radical art, individualism, machinery, and urbanization in an effort to unleash the vitality of the modern world.

In the opening salvo, "Long Live the Vortex!", Lewis explains, "Blast sets out to be an avenue for all those vivid and violent ideas that could reach the Public in no other way." He claims it "will be popular, essentially. It will not appeal to any particular class, but to the fundamental and popular instincts in every class and description of people, TO THE INDIVIDUAL...Blast is created for this timeless, fundamental Artist that exists in everybody." By producing a magazine, a cheaply-printed periodical easily carried home on public transportation, the creators of BLAST offered an iconoclastic alternative to the art exhibited on the walls of museums and literature printed by established publishers.

BLAST! Issue 2 - The Grip of War

Published in 1915 amidst the First World War, a year after the inaugural issue, the second issue of BLAST signaled the effects of the war on the Vorticist attitudes toward the machine age. Rather than the bold typography of the first issue, the second issue's cover design is monochromatic, featuring a woodcut by Wyndham Lewis. Subtitled the "War Number," the pages inside also lack the drama of the first one.

Less bombastic than the first, this issue offered more poetry and prose by Ezra Pound, Helen Saunders, and Jessie Dismorr and included many references to war. Famously, it also features "Preludes" and "Rhapsody on a Windy Night," two well-known poems by T.S. Eliot, who became associated with the movement through his friendship with Ezra Pound. Eliot's literary contributions to BLAST constitute his first offerings to a British audience. While the poems are not particularly "Vorticist" in their style, literary critic Rod Rosenquist argues that they play "'the straight man' next to the Vorticist pranksters, showing that lasting literary arts might also take their place in such a timely periodical."

Perhaps most significantly, this issue of BLAST featured Vorticist sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska's "Vortex: Written from the Trenches" in which he described his experience of the war. Gaudier-Brzeska reaffirmed his belief that the vortex of creative energy is the initial catalyst for making art, asserting, "My views on sculpture remain exactly the same. It is the vortex of will, of decision, that begins." At the end of the piece, there is a notice announcing that the artist was killed on June 5, only a short time before the magazine's publication, underscoring the direct and tragic consequences of war in the machine age. Later, Lewis and other members of the Vorticist group would also go into active service.

Vorticism According to Wyndham Lewis, and Beyond

As the movement's founder and leader, Wyndham Lewis is the usual starting point for understanding the movement. In one of the first articles written on the movement, Ezra Pound proclaimed him the leader of the group, hailing him as "a very great master of design." In 1956, Lewis stated that "Vorticism was, in fact, what I, personally, did and said at a certain period." While Lewis' actions sparked the Vorticist movement, many of the artists involved were active in taking the movement in new directions. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska worked closely with Ezra Pound to develop a theory of Vorticist sculpture. Their formulation was highly political, comparing the act of Direct Carving in sculpture to the political "direct action" desired by the anarchists.

Vorticist artist William Roberts also questioned Lewis' claim in a series of pamphlets with his own understanding of the movement. Shortly thereafter in 1961-62 Roberts painted The Vorticists at the Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel, Spring 1915, depicting himself along with Lewis, Ezra Pound, Cuthbert Hamilton, Fredrick Etchells and Edward Wadsworth, positing the six men as the core members of the movement, while marginalizing two of the women artists of the group, Helen Saunders and Jessica Dismorr, who were fundamental to the movement and its development.

Off the Page: Exhibitions of Vorticism

In 1915, after the publication of the second issue of BLAST, the Vorticist group held their first exhibition at the Dore Galleries in London. The exhibition was not widely publicized and mostly ignored by the general press. It included works by key members of the Vorticist group, including Lewis, Dismorr, Etchells, Gaudier-Brzeska and Saunders, as well as a number of non-Vorticist artists "invited to show" their work. Sadly, the news of Gaudier-Brzeska's death just a few days before overshadowed the exhibition.

In 1917, the poet Ezra Pound and American collector John Quinn organized the only contemporaneous Vorticist exhibition outside of England at the Penguin Club in New York City. Wartime conditions made it difficult to get the works to the U.S., and the exhibition went largely unnoticed.

Vorticism: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Poetry and Prose

Vorticism was notable for embracing a number of different art forms. The group laid emphasis on literary content as well as the visual aspects of the movement, thus increasing its far-reaching influence. The overheated rhetoric used by the artists in their writings ensured it a place next to equally vociferous groups like the Futurists and Dadaists. Wyndham Lewis himself was, first and foremost, a writer, and Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot (two of the most famous poets of the modernist period) were closely associated with the group. Additionally, other members of the movement who were primarily visual artists, such as Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and Jessica Dismorr, were encouraged to publish their literary writings in BLAST alongside their artistic work. Although Ezra Pound produced a number of poems, which he labeled "Vorticist," very little purely Vorticist poetry was produced. Most of what was published in BLAST can also be assigned to other literary movements.

Sculpture

Jacob Epstein and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska are the most notable sculptors associated with the Vorticist movement. Epstein did not sign the Vorticist manifesto in the first issue of BLAST, but his works dating from this period are closely related. Epstein's Rock Drill (1913) encapsulates the rise and fall of Vorticism: initially, Epstein created a vision of a human-machine hybrid that was to be nine-feet tall, but after seeing the machine-caused horrors of WWI he mutilated and truncated the work, leaving a maimed torso damaged by the machine it was once joined to. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska translated the Vorticist interest in movement into three-dimensional form. Interested in creating a "pure form," he used Direct Carving to find a distilled essence of his subject.

Painting

Vorticism saw its most important idea - the "vortex" - most fully developed in two dimensions on paper and canvas. The Vorticists, like the Futurists, were deeply interested in movement, in the whirling and turning of modern life, but they differed from their Italian counterparts in their interest in the static center of the vortex, in the stillness in the midst of motion. A central static element about which the rest of the painting turns is evident in Helen Saunders' Dance (c. 1915) and Wyndham Lewis' The Workshop (c.1914-5).

Publishing

The Vorticists' decision to disseminate their art and ideas in the form of a magazine (entitled BLAST) is highly significant. The format allowed them to combine visual art, design, and literature, uniting the creative endeavors of a movement that was fairly disparate in terms of its members and media. The magazine cost 2/6 (or half a crown in pre-decimalization British money), meaning it could be purchased by people who could not afford to collect art or even expensive poetry books, but very few people bought it at the time. Despite this initial failure to reach a large audience, BLAST, more than any painting, endures as one of the group's most important legacies, having influenced British sculptor Henry Moore and, later, musician David Bowie.

Later Developments - After Vorticism

In some senses, the Vorticist movement was over before it had barely started. The first issue of BLAST was published only weeks before the outbreak of the First World War, which changed the socio-cultural environment in Britain and caused the death of at least one important member - Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. The experiences of the war caused many people to reject the celebration of the machine, which had originally driven the Vorticist, and their bombastic dogmatism fell out of favor. Consequently, the Vorticists' few exhibitions did not stir much reaction, and individual artists moved on to other styles.

In 1920, Wyndham Lewis tried to revive the movement with Group X, a London exhibition that drew together some of the Vorticist artists again, but the group never cohered. These artists were now all taking their art in new directions and the movement's impetus had been lost. After this, Vorticism was generally little discussed by art historians, and during this time a number of significant works by Vorticist artists were lost.

Lewis continued to write and paint, although by the late 1920s he was painting less and writing more belligerently, attacking culture and those ideologies that he saw as prohibiting true revolution. During the early 1930s, he praised Adolph Hitler, writing one of the first biographies of the leader of the Nazi party, and while he distanced himself from these views by the end of the decade, his reputation was tarnished.

Sculptor Jacob Epstein continued to promote the expressive possibilities of Direct Carving, moving away from abstraction and concentrating on portraiture to reveal all aspects of humanity. The centennial of the founding of Vorticism ushered in a renewed interest in the group, with exhibitions in London and the United States excavating and repositioning the group within the history of English art as well as more internationally.