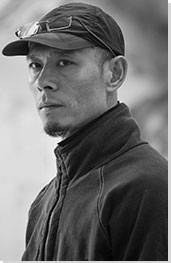

Summary of Zhang Huan

Zhang Huan's work is at times confrontational, visceral and personally dangerous, and it engages both implicitly and explicitly with problems of overpopulation, cultural erasure, political repression, poverty, famine, and want. He is one of the most significant contemporary artists working in China today, and a pioneer of Performance art within the country from the early 1990s. Although living in New York for a time, Zhang is part of a generation of contemporary Chinese artists that believe that modern China is the right context for the production of their work, with all its contradictions and difficulties as an emerging global superpower.

Originally making small (usually solo) performance work, Zhang is now an internationally renowned artist with a huge Shanghai studio, equipped and staffed to produce large-scale sculpture work. His career reflects the wave of modern Chinese art that became internationally recognized in the early 2000s, and his practice continues to shape and reflect the international art market's concept of active and significant Chinese artists.

Accomplishments

- Central to Zhang's work (and to the wider development of contemporary Chinese art) is the combination of Western artistic techniques and concepts with traditional Chinese cultural production. Rather than adopt alternative models of expression, Zhang is able to imbue modernist techniques of minimalism and abstraction with a strong Chinese and Buddhist cultural resonance, demonstrating that it is not necessary for Chinese artists to break with or deny their cultural background when making contemporary artworks. This has allowed him to retain his identity as an inherently Chinese artist whilst also achieving great success in the international art world.

- In his performance work Zhang built on the Western Performance art tradition of task-based performance, complicating simple tasks and activities through allusion and reference to Eastern cultural traditions. Deceptively basic activities, such as lying naked atop a mountain, are both an intervention in space in the tradition of Western artists like Dennis Oppenheim, and a reference to ancient Chinese folklore.

- Zhang's work often embodies the unique cultural context of contemporary China, which is caught between the capitalist impulse and the communist state apparatus. His more recent large-scale sculpture and installation, for example, are imposing and meticulously crafted pieces with great potential as commodities, but are also made from waste materials like incense ash (literally the remnants of past traditions and ritual) that undermine their ability to be moved or sold.

- Zhang's experience of New York, and his observations about the culture of America offer a new perspective on Western society to international audiences. Rather than seeing America as a place of freedom from the repression of his homeland, Zhang highlights the superficial nature of its multiculturalism and frequently myopic notion of exceptionalism. Zhang creates unapologetically from a Chinese perspective, with the West positioned as the 'Other', in an inversion of the colonial gaze. This is an important challenge to the Anglo-Centrism of the international art market, and a signal of the growing dominance of Chinese culture.

Important Art by Zhang Huan

Angel

For his first performance work, which appeared as part of a group show at the National Art Gallery in Beijing, Zhang placed a large white canvas on the floor of the exhibition space in the western courtyard of the gallery. He then smashed a jar filled with red food coloring and disembodied baby doll parts and covered himself with the jar's contents before attempting to reassemble the doll parts on the canvas. The red blood stood vividly out against the white canvas, spilling out over the floor and spattering the steps leading to the courtyard. Zhang later strung up the partially reassembled dolls as grim trophies.

The performance piece invoked many associations for its original Chinese audience. The bloody scene reminded many of the June Fourth massacre at Tiananmen Square (1989), for example, where images of similarly vivid blood against steps and street were widely seen. The juxtaposition of the child-like doll parts and the blood red color also reminded many Chinese citizens of the Young Pioneers, the youth movement of the Chinese Communist Party who were recognizable by their red neckerchiefs. But perhaps most notably the blood red dye and mangled doll parts brought to mind China's controversial "One-child" policy (effective 1979-2016). Zhang himself knew of many women close to him who were forced to undergo abortions as a result of this policy. The strung-up babies that were left as relics of the performance were a stark representation of the human cost of the policy and the psychological scars left.

As art historian and curator Thom Collins writes, "This work, a startling and visceral commentary on the Chinese government mandate of abortions for women conceiving more than the legal limit of one child, led to a quick closure of the exhibition and serious censure of the artist." Not only was the group show promptly shut down, but Zhang Huan was fined 2000RMB and forced by the National Art Gallery to write a self-criticism. He did this only so that the group show would be allowed to continue, but it never re-opened and Zhang was blamed by the other participants. He received several negative comments from his peers as well as his teachers. He was told by some that he only took off his clothes because he had no talent for painting. Others said that he was "out of his mind" and a "complete pervert". Yet Zhang did not allow himself to be deterred, and his friend, the artist Ai Weiwei, encouraged him to continue with his performance-based work.

Performance - National Art Gallery Beijing

12 Square Meters

In this work, carried out on June 2, 1994, Zhang slathered his naked body in fish oil and honey, and proceeded to sit motionless in a public toilet for exactly one hour as insects crawled all over his body, including into his mouth and up his nose. Throughout the performance, Zhang maintained a calm, yet tough, almost meditative demeanor and facial expression. At the end of the hour, he arose, slowly walked to a nearby pond, and entered until he was completely submerged. The performance was documented in black and white photographs by the Chinese photographer Rong Rong.

This performance piece was directly inspired by Zhang's memories of growing up in an overcrowded village. One day in 1994, he needed to use a restroom after lunch and entered a public restroom just off the street. He found that the restroom had not been cleaned for some time, as the area had been experiencing flooding. The putrid smell and swarms of flies left their mark on his memory. As he recalls, "Once I stepped in, I found myself surrounded by thousands of flies that seemed to have been disturbed by my appearance. I felt as if my body was being devoured by the flies." By re-creating this situation, he presented a phenomenological account of his personal experience of overpopulation, one which many Chinese citizens are likely to be able to identify with and calling attention to the issue. Zhang's performance was an endurance feat that forced its audience to reconsider what might otherwise be a familiar and everyday space, recognizing the injustice of the squalor.

At the time, Zhang was quickly learning that using his body to enact Performance Art allowed him to experience a unique sort of catharsis, particularly in response to traumas and anxieties. He notes that in his youth he was often verbally and physically attacked by strangers, simply because he had a strange appearance and style of dress. He says, "I have always had troubles in my life. And these troubles often ended up in physical conflicts [...] All of these troubles happened to my body. This frequent body contact made me realize the very fact that the body is the only direct way through which I come to know society and society comes to know me. The body is proof of identity. The body is language."

During a 1999 interview with art historian Qian Zhijian, Zhang shared his personal philosophy that sometimes "the best way to get rid of the horror and to return to a state of ease might be to torture the body itself to calm it". He went on to say that "each time I finish a performance, I feel a great sense of release of fear". Indeed, in this and other performance pieces that physically challenged his body, Zhang enters a meditative state of mind, during which he keeps entirely calm to be able to endure and overcome physical discomfort, sometimes even reporting that he hallucinates while doing so. He recalls that while he was performing 12 Square Meters, "I first felt that everything began to vanish from my sight. Life seemed to be leaving me far in the distance. I had no concrete thought except that my mind was completely empty." This ability to enter a meditative state reflects his Buddhist spirituality, which would become a more central aspect in his later works.

Performance - Beijing East Village

To Add One Meter to an Anonymous Mountain

In 1995, shortly after the artistic community of the Beijing East Village had been forcibly disbanded, Zhang and several other member artists - Wang Shihua, Cang Xin, Gao Yang, Zuoxiao Zuzhou, Ma Zongyin, Zhang Huan, Ma Liuming, Zhang Binbin, and Zhu Ming - collaborated on this performance, wherein they climbed to the peak of a nearby mountain, stripped naked and lay one on top of each other to create an additional peak. To assist in the creation and documentation of the work, the group hired two surveyors and some equipment from the land bureau and also arranged for photographers and film cameras from a movie studio to be present.

The work was inspired by an old saying, "Beyond the mountain, there are more mountains". Zhang explained that the work "is about humility. Climb this mountain and you will find an even bigger mountain in front of you. It's about changing the natural state of things, about the idea of possibilities." The cultural resonance of this saying is an excellent example of Zhang's use of a performance tradition most associated with the West (naked public interventions) in order to reflect a Chinese perspective. The performance echoes Western works like Dennis Oppenheim's Parallel Stress or even Yayoi Kusama's Naked Happenings in New York, but does so to reframe an ancient proverb. It demonstrates how similar actions might provoke extremely different resonances according to the site of their performance.

Collaborator Kong Bu recalls the meticulousness with which the group executed and documented the performance, saying, "At 13:00 on May 11, 1995, only the occasional truck along the highway disturbed the calm atop the mountain. Surveyors Jin Kui and Xiong Wen stood on the road below where they set up their equipment. They measured the mountain's height at 86.393 meters. I was in charge of recording each participant's weight. Everyone climbed the mountain, and one by one the artists shed their clothes. The participants divided into four rows by ascending weight and then lay on top of each other in the form of a pyramid. Between 13:26 and 13:38 that afternoon, the surveyors' measurement of the anonymous mountain was 87.393 meters, precisely one meter higher than Miaofengshan Mountain."

A secondary idea presented by this performance is the connection between man and nature. By using their naked bodies to augment the size of a mountain, the participating artists put forth the idea that man and nature can become one. They further explored this idea in their very next collaborative performance, carried out later the same day, titled Nine Holes, in which they travelled to another nearby mountain where the men dug holes in the earth into which they inserted their penises, and the women aligned their vaginas with protrusions on the earth, becoming one with the mountain. Zhang also explored the connection between man and nature in The Original Sound (1995), a performance wherein he filled his mouth with earthworms and allowed them to crawl around his mouth and over his face and body. He recalls "I liked the feeling of the worms creeping into my mouth and ears and onto my face and body. I felt as if I were one of them. I think man and earthworm are similar creatures in the way that they are related to the earth. They come out of the earth, but eventually they all go back into it."

Performance - Miaofengshan Mountain, Mentougou District, Beijing

Family Tree

Family Tree consists of nine sequential images of Zhang Huan's face, taken from dusk to dawn. As the images progress, Zhang's face and shaved head is gradually covered by calligraphy (written by three calligraphers) until it is completely black. The photographs are taken in a chronological order, from early morning to nightfall, and arranged in a grid of three columns.

This performance aimed to represent Zhang Huan's lineage, with the calligraphers writing names of his family members, as well as personal stories, Chinese folktales and poems and random thoughts. The blacking out of Zhang's face by the end of the process served as a metaphor for the way that his identity might be entirely subsumed by his heritage. The density of cultural history obscures the individual, only for it to become clear again in the final image, where Zhang appears more animated and the legibility of the writing has entirely faded. Christopher Philips, curator at the International Center of Photography, writes of the piece, "As you see his face slowly disappearing beneath the blackness, you come to feel the elaborate web of social and cultural relations smothering any sense of the individual. But Zhang's stubborn, unchanging, expression suggests resistance - a refusal to allow his identity to be consumed by the tide of tradition."

Zhang explains his motivation for the piece, saying "More culture is slowly smothering us and turning our faces black. It is impossible to take away your inborn blood and personality. From a shadow in the morning, then suddenly into the dark night, the first cry of life to a white-haired man, standing lonely in front of window, a last peek of the world and a remembrance of an illusory life [...] My face followed the daylight till it slowly darkened. I cannot tell who I am. My identity has disappeared. This work speaks about a family story, a spirit of family." He continues, "In the middle of my forehead, the text means 'Move the Mountain by Fool (Yu Kong Yi Shan)'. This traditional Chinese story is known by all common people, it is about determination and challenge. If you really want to do something, then it could really happen. Other texts are about human fate, like a kind of divination. Your eyes, nose, mouth, ears, cheekbone, and moles indicate your future, wealth, sex, disease, etc. I always feel that some mysterious fate surrounds human life which you can do nothing about, you can do nothing to control it, it just happened."

This work was likely inspired by Qui Zhijie's 1986 piece titled Writing the 'Orchid Pavilion Preface' One Thousand Times, wherein the artist copied a famous calligraphic passage over and over again until the writing surface was entirely black.

Chromogenic prints - The Walther Collection

My New York

In this performance work created for the 2002 Whitney Biennial, Zhang was covered with a white cloth and carried out to the courtyard of the Whitney museum on a palanquín. There, he stood up and removed the sheet, revealing that he was wearing a muscled body suit made entirely of raw meat. He then proceeded to walk around the city streets in this suit, barefoot. During his walk, he also handed out several white doves to onlookers to release. After crossing the street and walking around the perimeter of the museum, he returned and disappeared into the museum, ending the performance.

This work was a result of Zhang's crisis of identity upon moving to New York City, where he became unsure of who he was as a person and as an artist. He created the suit out of meat to represent his perception of the inherent animal nature of mankind, which he found to be even more prominent and perceptible in New York than in China. The suit also served as a protective body covering that gave the artist an imposing and intimidating presence, as it made him appear much larger and more muscular than he actually is. He notes, "A bodybuilder will build up strength over the course of decades, becoming formidable in this way. I, however, become Mr. Olympic Bodybuilder overnight." On the other hand, the releasing of the white doves is a Buddhist gesture of compassion, which carried a much stronger significance as the 9/11 attacks in New York had occurred only a few months previously and the city was still in the process of grieving. Thus the work represented Zhang's mixed feelings about his new life in New York. On one hand, he felt vulnerable, as if he needed to modify his physical appearance in order to protect himself from the physical and psychological dangers of the metropolis, yet at the same time he felt a sense of liberation that he had not felt living in Beijing. Zhang says of the work, "the body is the only direct way through which I come to know society and society comes to know me. The body is the proof of identity. The body is language."

This was not Zhang's first work that dealt with the difficulty he faced in getting used to life in the United States. In 1999 he carried out My America (Hard to Acclimatize) at the Seattle Asian Art Museum. For the performance, he had 56 naked American volunteers stand in rows on a scaffold and throw stale bread at him. This contrived experience of bullying represented the discomfort and humiliation he felt throughout the difficult process of assimilating into a new country and a new culture. The notion of alienation and unfamiliarity with the traditions of the West is an interesting inversion and challenge to the 'exotic' notion of China. In his American work it is Zhang who sees the other society as strange, unwelcoming and inscrutable, encouraging an international audience to consider their own position as spectators.

Performance - Whitney Museum, New York City

Long Ear Ash Head

This sculptural work takes the form of an enormous head with closed eyes and excessively long earlobes that trail along the ground, with the sculpture finishing just above the mouth. Above the eyes, the top portion of the head has been lifted slightly from the bottom portion. The features on the head are inspired both by Buddha's features, as well as the artist's own. There are other forms emerging from the surface of the sculpture, including a laughing buddha on top of the nose, and two dolls on the scalp. This work was presented as part of "Zhang Huan: Altered States", which was the first major solo show by a living artist at the Asia Society in New York.

This work is one of the first that Zhang completed upon returning to China and setting up his workshop in Shanghai. The work that he has produced from this point onwards marks a significant shift in his attitude and oeuvre, abandoning the provocative, often shocking performance art of his past and instead turning toward Buddhism and Chinese tradition to create objects imbued with a sense of serenity. In Buddhism, elongated earlobes represent happiness and good fortune. The use of incense ash, brought in from some twenty Buddhist temples around Shanghai, is something that Zhang has spent several years experimenting with in various works (including Berlin Buddha (2007) and Sydney Buddha (2015), as well as his series of grayscale "ash paintings" which resemble Anselm Kiefer's materially dense canvases). He says of his work with ash, "I created a new genre, a new phenomenon. There are so many different ways to use ash; I probably won't lose interest in it for a while. It moves me the most - it's able to seep through me. What's left in it are the remnants of so many souls." This notion of creation from waste or discarded material echoes the changing nature of China, where reappraisals of things lost in the transition to superpower is a key concern of contemporary artists. Zhang also makes references to his own past in this work, particularly with the two dolls that reference his earliest performance piece, Angel (1993).

By blending the features of Buddha with his own, Zhang presents a sort of new self-portrait that indicates the tranquility he has found in more recent years. He explains, "I really want my inner state to be more Buddhist, and by transforming myself physically, externally, with the long ear lobes, somehow I can get closer to enlightenment and to becoming Buddha. Also, I opened up my head and revealed the brain to symbolize that I want to somehow absorb all the qualities of life." He also notes that "I feel I am so lucky to change from a mad man to a man with good food and a family man, to have my children. I feel that Buddhism has blessed me." When asked why the Buddha is missing a mouth, he responded "Somehow if you stop breathing, you transcend life and death. You're in an eternal state."

Incense Ash, Wood, and Steel - Asia Society, New York

Biography of Zhang Huan

Childhood

Zhang Huan was born into a farming family in Anyang City, Henan Province (Southern central China) and originally known as Zhang Dongming, a name meaning 'Eastern Brightness'. Zhang grew up knowing struggle, spending his first eight years living with his grandmother in the countryside in Tangyin County. He says that growing up in such a central part of the country strongly shaped his identity, explaining that "Henan combines the masculine North and the feminine South. So I have both qualities." He and his family struggled to earn enough money to survive. He had a hard time in school saying that he was "wild", and could never concentrate in class, as well as struggling more generally with Chinese social convention. He also experienced many deaths throughout his youth, both of his family members and of political leaders. He was born a year before the start of the genocidal Cultural Revolution in China, and was embarrassed by his revolutionary name, which was a recognizable homage to Chairman Mao.

Education and Early Training

After private painting lessons at fourteen he was awarded a place at the Henan Academy of Fine Arts in Kaifeng. He received his B.A. in painting from Henan University in 1988. While studying there, he was most engaged and inspired by Jean-François Millet and Rembrandt van Rijn. His graduation piece was a painting with the title Red Cherries (1988), which showed a mother peacefully nursing her baby next to a bowl of cherries. He remained at Henan University as a teacher in the art department for the next three years before moving to Beijing where he changed his name, abandoning the revolutionary connotations of 'Dongming'. He received his M.A. in painting from the China Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing in 1993, an institution he was attracted to for its emphasis on the European classical tradition.

After graduating, he worked for one month at a commercial painting company in Beijing where he was tasked with making copies of Degas' works. His reproductions were excellent and earned a great deal of money for his employers. However, he only received a salary of 250RMB, which was far less than weekly expenses, and when he asked his boss for a raise he was yelled at rudely. On the way home, he was so upset that he punched a bus, which he now thinks of as his first conscious act of self-torture and perhaps a precursor to his later performance actions.

Around this time, Zhang felt unsure of what to do next as he didn't feel as politically-minded as his Chinese painter contemporaries and had hopes of discovering an alternative to painting. He was also extremely poor. He moved to a dirty, run-down artist's community on the edge of Beijing, formerly known as Dashanzhuang, but renamed the East Village by its artist inhabitants (after New York City's East Village, which the residents felt had an affinity with their experimental and collaborative aesthetic). He spent this time listening to Nirvana, Cui Jan (Chinese rock and roll) and Buddhist music and feeling increasingly depressed, but also making friends with the other artists who lived in this "glorified garbage dump". It was here, with little resources available to him to make art, that Zhang began to use his own body, as well as the bodies of his artist friends, to create performances. The members of the Beijing East Village were also inspired by the provocative "living sculptures" and other artworks of British artists Gilbert and George, who paid a visit to this avant-garde community in October 1993 while in Beijing for an exhibition.

The Beijing East Village community was closed by the police only a year after it began, following the arrest of Ma Liuming for cooking naked in a courtyard. The authorities had been displeased with what they considered to be the "inappropriate" goings-on of the community for some time, and jumped at the opportunity to make an arrest and shut it down for good. Yet the artists who lived there continued to collaborate and became the first generation of Chinese performance artists to produce work consistently within the country.

Mature Period

From this point onward, Zhang focused on using his (usually naked) body, in an attempt to address and critique various issues, including (as described on his website) "The power of unified action to challenge oppressive political regimes; the status and plight of the expatriate in the new global culture; the persistence of structures of faith in communities undermined by violent conflict; and the place of censorship in contemporary democracy." Some of his early performances involved extreme physical actions, such as strapping himself to a board hung from the ceiling while a medic siphoned his blood onto a hot plate, or locking himself inside a metal box with only a small slit for air.

In 1998, he visited the United States to carry out a solo performance titled Pilgrimage: Wind and Water in New York at P.S. 1. This was the first time he used overt Chinese imagery and symbolism in his performance work. For the piece, he walked slowly across the museum courtyard as Tibetan music played, until he reached a traditional Chinese bed, but one that held blocks of ice instead of a mattress, and which was surrounded by several live dogs. He then undressed, and lay face-down on the ice for ten minutes. The work was what he considered "glocal", combining both global and local elements (representing both China and the United States at once). He said of the work, "The use of dogs originates from my impression of New York. There are so many dogs in this city, and they are very well taken care of. But like human beings, dogs are sensitive to the external environment and are afraid of possible dangers. What strikes me the most about this city is the co-existence of different races and their cultures. By the term fengshui, I am referring to the vitality and vigor of this metropolis characterized by the co-existence of cultures. Yet for me, there is a fear, or culture shock, if you like. I do like the city, but at the same time, I have an unnamable fear. I want to feel it with my body, just as I feel the ice. I try to melt off a reality in the way I try to melt off the ice with the warmth of my body."

Despite this complex first impression of the city, Zhang decided to move to New York later that same year with his wife Jun Jun, particularly as many of the works he had been making were only able to be shown outside of China. He says "At that time New York was the city of my dreams, so I wanted to go try my luck." In New York, he quickly fell into a schedule of performances and commissions from prestigious cultural institutions. Both of his children were born there, in 2000 and 2003. However, after eight years of living in the city, he began to grow tired of both America (in part because he felt that living there put too much distance between him and his Buddhist roots), and of Performance art itself. A fortune teller told him that the most suitable place for his next move would either be Eastern China, or somewhere to the Northeast of his birthplace (Henan province). In 2006 he moved back to China to live in Shanghai. He reflects on his time living in New York, saying "Since we've been living in China we look back on those years spent in the West as lost years. China has given me more passion and drive. New York made me sick at heart. China helped me to forget that."

With his move back to China, he decided to take a step back from Performance art. He explains that "In 2005 I did three different performance pieces, and after the last one I realized that I was starting to repeat myself. There weren't good ideas coming out, and also I felt really tired. So I decided to stop cold turkey." He opened an enormous studio in Shanghai's southern Min Hang district, where his team of over 100 assistants produce object-based art, particularly sculpture. However, he notes that his experience with performance art helped him significantly with this newer object-based practice, saying "It taught me how to conceptualize a work from beginning to end and it allowed me to live through the process of making art." He took over the 75-acre building where his studio currently stands after a fire ended the company's operations. He explains that "In China, it's believed that once you move into a place that's burned, your business will catch fire." Indeed, once back in China, he was no longer a small fish in a large artworld pond, and experienced high levels of fame in his homeland, where he lives with his wife and two children in a simple home. Every day at his studio, he takes a lunchtime nap underneath his desk in a two-foot-high space fitted with a mattress, pillow, sheets and comforter. He explains "I feel safe on a low level. It quiets me down."

Zhang has been represented by Pace Gallery, New York, since 2007. Although now working in sculpture and oil painting rather than performance, the body still features prominently in his works, particularly recreations of the fragmented body parts of Buddhist statues using incense ash from Buddhist temples. Returning to Buddhism has been a critical turning point in both his life and career. Rather than following a single school of Buddhism, Zhang says that "As long as they're part of the Buddhist tradition, I like them all. It doesn't matter which one. Also, I have the greatest respect for other religions. It doesn't matter which religion we're talking about, the core concept is the same - just as you are white and I'm yellow, but at the same time, on a human level, we are the same."

In 2009, Zhang also worked as the director and set designer of an experimental production of Handel's 1743 opera Semele, at the Theatre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels. Zhang was intrigued by the ancient Greek comedy's plot's relation to Buddhist ideas of reincarnation and karma.

The Legacy of Zhang Huan

As contemporary Chinese art scholar Gao Minglu notes, "The Chinese term for performance art is 'Xingwei Yishu', which in English means roughly 'Behavioral Art'. Obviously, behavior has a different meaning than the original sense of performance. The concept of 'behavior' is not limited to the physical actions of the individual but also encompasses the moral sense of the individual expressing himself within a community or within a social structure. This point relates to the Chinese Confucian tradition. In the Chinese Confucian tradition there is no such thing as purely individual behavior, all individual behavior is social and all behavior reflects some types of social relationship."

Zhang has boldly rejected the "accepted" art that Chinese authorities expect artists to produce, and has not allowed censorship to deter him from carrying out projects that shock and dismay. Other Chinese artists have embraced this philosophy, as exemplified by the underground OPEN festival of performance in Beijing, whose artists similarly challenge propriety in the way that Zhang and his contemporaries (such as Ai Weiwei and Zhe Yu) have done consistently. Even as recently as 2014, a program about Zhang that aired on the Discovery Channel in Asia was banned in China.

Zhang has set an example to other artists that they do not need to be afraid of making significant changes in their careers. As curator, critic, and gallery director David Teh writes, "[Zhang's] name had become synonymous with Chinese performance art. But Zhang's recent return to China and his pursuit of new formal directions yield fresh perspectives on some timeless ideas that haunt his work."

Influences and Connections

-

![Chris Burden]() Chris Burden

Chris Burden -

![Vito Acconci]() Vito Acconci

Vito Acconci -

![Gilbert and George]() Gilbert and George

Gilbert and George ![Gunter Brus]() Gunter Brus

Gunter Brus- Qui Zhijie

-

![Ai Weiwei]() Ai Weiwei

Ai Weiwei - Rong Rong

- Wang Shihua

- Cang Xin

- Gao Yang

- Zhu Yu

- Yang Zhichao

- He Yunchang

-

![Ai Weiwei]() Ai Weiwei

Ai Weiwei - Rong Rong

- Wang Shihua

- Cang Xin

- Gao Yang

-

![Performance Art]() Performance Art

Performance Art - Contemporary Chinese Art

Useful Resources on Zhang Huan

- Zhang HuanBy Yilmaz Dziewior, Zhang Huan, RoseLee Goldberg, Robert Storr, Michele Robecchi, and Craig Garrett

- Performance Art in ChinaOur PickBy Thomas J. Berghuis