Summary of Charles Rennie Mackintosh

A close friend of his once said, "the creations of Mackintosh breathe", and as such likened the architect to a prophet giving life to the otherwise ordinary and inanimate. Self-consciously understated, and in the same key as a simple monastery or a white cube contemporary art gallery, both the interior and exterior spaces designed by Charles Rennie Mackintosh sing of serenity, spirituality, and of rigorous attention to detail. Although an architect working with colossal and hard materials, he typically brought intimacy and softness to all that he designed and built. His symbolist architectural style is one infused with the restraint and minimalism of Japonism, as well as fine delicacy and a love for floral motifs shared with his long-term partner and artistic collaborator, Margaret Macdonald.

As the visionary architect responsible for its re-design and re-build, Mackintosh not only transformed The Glasgow School of Art into world-renowned academy, but also put Scotland firmly on the map as a center of creativity and hub for art and design. His most intense work period lay between 1896-1910 - designing buildings, as well as all types of furniture and other decorative features - but he also drew and painted until his final days. Like his European counterparts, including Gustav Klimt, Mackintosh integrated a multitude of curves with straight lines but did so without the same ostentation, opulence, and grandeur. In 1900, he was invited to present an installation at the 8th Secessionist Exhibition in Vienna and following his display he was appropriately acknowledged as one of the foremost designers in Europe.

Accomplishments

- Mackintosh worked in close collaboration with his wife Margaret Macdonald, his friend Herbert MacNair, and his wife's sister Frances Macdonald (who was married to MacNair); together they were known as "The Four". They developed The Glasgow Style that was similar in intent to William Morris and The Arts and Crafts Movement, believing in the "total design", that is the creation of every aspect of an interior including furniture, metalwork, and stained glass.

- Interestingly, although European Modernist contemporaries said that they sought to break with tradition, lavish materials often pointed back to the wealth and elitism from which they wished to dis-associate. Mackintosh on the other hand, achieved a humble simplicity in design - both for the exterior and the interior furnishings of buildings - and sought for, above all, integrity of materials and harmony of space. Indeed, taste not wealth was always a key focus for Mackintosh.

- Aside from being a highly imaginative visionary architect and interior designer, Mackintosh in his later years became an avid painter of flowers. Interestingly, fellow modernist, Piet Mondrian was also a prolific flower painter as an aside to his famous primarily color abstractions. The act of painting flowers well exposes an artist's intention, that of a manmade attempt to capture the exquisite perfection of nature.

- Although Mackintosh himself ironically stated that part of his impetus to create art was to make something "more lasting than life itself", it seems that in many ways his career gives insight into the opposite message. The fact that most of Mackintosh's designs were never materialized, and furthermore, that recently one of his greatest buildings has been irrecoverably damaged by fire raises the poignant question as to whether anything can, or should, exist eternally. This debate is particularly current as impermanence is a topic that is in vogue throughout modern art, for example, the contemporary sculptor Urs Fischer makes larger-than-life figures into candles and lets them melt away.

Important Art by Charles Rennie Mackintosh

Glasgow School of Art

Mackintosh redesigned both the interior and exterior of the Glasgow School of Art to stand as a shining example of his early, forward-looking, pluralist architecture. The building was made of stone in order to reference Scottish Baronial tower houses, which Mackintosh considered incredibly modern in their original use of iron and glass. Mackintosh was always sensitive to surrounding architecture and existing national traditions but at the same time added his own free style aesthetics; on the left-hand side of the building there is an entrance reminiscent of an ancient ziggurat built to unusual, non-classical proportions. As such he seamlessly merges a wide variety of different influences.

Perhaps most prominently, and especially in the interior, Mackintosh displays his interest in Japanese design; as well as overall restrained decorative elements. He created a functional iron screen on the North facade which bears similarity to Japanese heraldic emblems or 'mon'. The exterior of the building served as notable inspiration for Bauhaus director Walter Gropius' Fagus Factory (1911-13), through its very similar rectilinear composition and window design.

From a philosophical perspective, Mackintosh sought to unite the body and spirit, and beauty and function through perfectly designed interior space. The library was built at the heart of the art school building and inside the space was carefully divided by wooden beams akin to Japanese houses and illuminated by large windows. This part of the facade stands in contrast to the East Front where windows were kept to a minimum. Art historian Alan Crawford described this part of the building, "a pause in the design, such as occurs between the chapters of a book or the verses of a poem."

The studio spaces within were simple and austere but were decorated - by balancing contrast - with exuberant floral ironwork akin to Hector Guimard's classic Art Nouveau designs for the Paris Metro (1900). Art historian Nikolaus Pevsner claimed such juxtapositions as "essential to grasp the fusion in his art of puritanism with sensuality." Traditionally furniture was viewed as an extension of architecture but for Mackintosh it served as more of a complement. The square chandeliers in the library as well as the curved and colorful shapes in the stained glass windows clearly highlight the artist's interest in Symbolism, and overall, the building has been dubbed by writer Cairney as "Mackintosh's self-portrait" and by the design historians the Fiells as "Mackintosh's masterwork".

Stone, Glass, Iron, Wood

Interior for Mackintosh's Mains Street Flat

Mackintosh began to design the interior for his own Glasgow flat shortly before his marriage to Margaret Macdonald, and the two of them moved in soon afterwards. While Mackintosh largely left the original features intact he rearranged the rooms to create what Cairney has praised as a "living, three-dimensional work of art, a breathtaking space within four square walls". One of Mackintosh's friends, Muthesius, described the home as a "fairy-tale world" and noted that even a book left out would disturb the minimalist and perfectly harmonious scheme. Even the fireplace had been lovingly modified with a curved wooden top piece in order to soften it and to make the overall space feel more homely. The couple's furniture, pictures, and cushions for the cats were added.

There is a strong disregard for materialism illustrated by the clean lines, delicate coloring, and generally uncluttered interior. As such we are presented with a stark contrast to the heavily draped, ornate, and dark more typical British Victorian interior. Some furniture was brought from Mackintosh's Regent Park dwelling and modified slightly, whilst the tables, a smoker's cabinet for the dining room, a white writing desk and new decorative panels by Macdonald were all made specifically for the new residence. Quiet complementary color schemes were created, mostly grey and white, or brown, black and white (in the dining room), and this was all off set and completed by select Japanese prints and subtle arrangements of twigs and flowers.

It has been suggested by art historian Pamela Robertson, that the photographs taken of this flat could be considered misleading, for they were all taken in black and white. They were in fact highly interested in color and drawn to the enriching effect that touches of color could have. For example, the panels in the artists' bedroom were green and their stained glass was purple. They did not omit color as much as create a neutral space so that one could actually see color, a bit like a gallery in that respect.

Wood, glass

Installation for the Eighth Secessionist Exhibition

In 1900 Mackintosh and Macdonald were invited by the architect and figurehead of the Viennese Secession, Josef Hoffman to present a collaborative design for "The Scottish Room" at the 8th annual exhibition of the movement held in Vienna. The result was a recreation of one of the many tea room interiors that Mackintosh had designed in Glasgow. Changes were made furnishing the space however, making it relatively sparse overall, but with a show-stopping piece by Macdonald hanging on the wall. Macdonald had made a large oil-painted gesso on hessian piece (her typical media) that featured five women depicted in her signature overlapping and floral style. It had originally been made for Miss Cranston's Ingram Street Tea Room and named The May Queen. Admired greatly by Mackintosh, he said of his wife's work, "Margaret has genius, I have only talent".

Some of the furniture included was in fact brought from the couple's Mains Street flat, whilst other pieces were made especially for the space. A magazine at the time, The Studio commented on the spirituality of the installation; "The composition forms an organic whole... the effect of sweet repose filling the soul." Muthesius, writing for Die Kunst, praised this installation as having "a seminal influence on the emerging new vocabulary of forms, especially and continuously in Vienna."

Mackintosh's biographer, Thomas Howarth wrote that after this exhibition the "the entire Viennese movement blazed into new life" with an "outpouring of decorative work and furnishing... bearing a striking superficial resemblance to that of Mackintosh." Two of the best examples of direct influence following Mackintosh's iconic display are Hoffman's Sitzmachine Armchair (1905) and Gustav Klimt's Beethoven gesso frieze (1902), although Klimt is more likely to have been influenced by the work of Macdonald.

Wood, glass, textiles

Room de Luxe in the Willow Tearooms

Tea rooms were a popular alternative to working men's clubs in Glasgow and had arisen from the campaigns of Scotland's vibrant Temperance movement (which stood against the consumption of alcohol). Catherine Cranston opened a number of these tea rooms in Glasgow and all were designed by Mackintosh, to whom Cranston had entrusted complete creative freedom.

The Willow Tearooms, shown here as they appear now, were originally decorated with dark timber beam ceilings that were once again heavily inspired by Japanese design. Upon entering the building's entirely white facade, visitors were naturally guided around the space by the tall back chairs and assortment of decorative metal screens. A repetitive series of wall panels showcased images of roses, peacocks, tall women, and fruits. The motifs were all directly related to systems of thought outlined by the Symbolist avant-garde and accordingly, often spurred controversy as visitors read sexual connotations in the work. Art historian, Alan Crawford interpreted these opinions to highlight "a gap between public, ornamental functions and private, symbolic meanings."

Mostly, such controversy was encouraged in order to increase footfall through the tea room. Mackintosh even designed the dresses and chokers of the serving waitresses, arranged and ordered the flowers, and designed different colored bells for ordering with glass balls which dropped to the kitchen. This was indeed a "total design", and the famous architecture historian, Nikolaus Pevsner noted that "[i]n the Cranston tea-rooms extraordinary effects were created in the surroundings...".

Wood, glass, textiles

Hill House

This building once again highlights Mackintosh's eclectic tastes and influences. He said himself, "It is not an Italian Villa, an English Mansion House, a Swiss Chalet, or a Scotch House. It is a Dwelling House." Here in particular, as well as traces of the Scottish Baronial style, there is also strong influence coming from the Arts & Crafts movement, and more specifically, from the architecture of CFA Voysey.

Incredibly thick walls push the front door into a recessed portico so it appears like a portal between two different worlds, that of Mackintosh, and that of everyone else. Indeed, it was the interior of this building that was designed first and the Fiells note that "each of his architectural and interior projects must be considered as complete organic unities in which the whole was very much more important than the sum of the individual parts." The library, similar in part to that of the Glasgow School of Art was built of tall, dark wood and surrounded by highly colored and enameled glass. Light floods into the house from the top of the stairs and the reflections from stained glass windows - featuring flowers and nude women - change as the sun moves throughout the day. For the exterior, Mackintosh presented his usual asymmetrical window organization, and solid and yet still somehow soft-looking walls.

Since the terrible fires at The Glasgow School of Art, Hill House is now the only Mackintosh building to still stand in its entirety.

Stone, iron, glass, wood, textiles

Fritillaria

By 1900 Mackintosh's flower studies had begun to emerge as an important part of his overall body of work. Having left London and staying in Walberswick in Suffolk he completed approximately 30 flower watercolors in a standard format intended for a book publication. Unfortunately this plan did not come to fruition due to the onset of the First World War.

In this example the washes are saturated while still stylized and as such, Cairney noted that they show "botanical exactness coupled with... artistic fancy." Many of Mackintosh's flower paintings and other botanical illustrations were created in collaboration with Margaret Macdonald. Indeed they are signed with both artists' initials, 'CRM MMM'. The font of this text is a special one invented by Mackintosh and links this later work to the posters that he had produced earlier in his career. Mackintosh noted how "Art is the Flower - Life is the green leaf. Let every artist strive to make his flower a beautiful living thing... you must offer the flowers of the art that is in you - the symbols of all that is noble - and beautiful - and inspiring." This watercolor also serves as an important midway point between earlier Symbolist watercolors that were translated into design features, and his more commercially minded landscape paintings made whilst living in France.

Watercolor - Hunterian Museum & Art Gallery, Glasgow

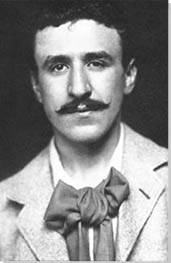

Biography of Charles Rennie Mackintosh

Childhood

Charles Rennie Mackintosh was the fourth of eleven children, and one of seven to survive infancy, born to parents Margaret Rennie and William Mackintosh. His father was a policeman whilst his mother was usually bedridden due to being so often pregnant, recovering from birth, or unwell. Mackintosh's large - mainly female - family was tight knit and lavished him with love and affection. The family's first tenement was situated on Parson Street overlooking the gothic Glasgow Necropolis; their father tended a vegetable garden and such became an early influence on Mackintosh who developed an avid interest in organic and botanical form and growth. From a young age Mackintosh did lots of drawing and used his sketchbooks as a way to withdraw from the world and to manage difficulties understanding the emotions of others as well as his own outbursts of rage. Also during childhood, Mackintosh was afflicted with rheumatic fever; this resulted in a droop on one side of his face and developed into a signature feature of his appearance.

The aspiring, upper-working-class family managed to buy a two-story terraced house in Glasgow's new residential suburbs. Here Mackintosh first had his own room, a study bedroom in a large basement. Even in this home, one of Mackintosh's earliest dwellings, he immediately touched the place up with beautiful artistic delicacy; remodeling the fireplace and adding distinctive decorative friezes to the walls.

Education and Early Training

In 1877 Mackintosh began his studies at Allan Glen's High School where he specialized in architectural and technical drawing. From the age of 15 to 25 he studied part time at the Glasgow School of Art while also interning with renowned architect John Hutchinson, already receiving challenging commissions. His family always supported him, but often voiced concerns regarding his heavy workload. Mackintosh trained as a painter under the guidance of the director of the school at the time, Francis Newberry. Newberry encouraged a looser style in painting and suggested architecture classes. Mackintosh's mother died when he was 17, a sad event which brought the family even closer together. After this Mackintosh travelled around Europe, spending most of his time in Italy, filling sketchbooks with views of Romanesque, Byzantine, and Gothic buildings but generally avoiding the Classical.

Following his return to Glasgow in 1889, Mackintosh was offered a job by the reputable architecture firm Honeyman and Keppie where he began to develop and promote his own style and philosophy. It was also here, working in an office environment, that the young architect started to display personal difficulties dealing with compromise. He became engaged to John Kelpie's sister Jessie in 1891, but when he treated her badly and broke off the engagement it resulted in strain on his position within the firm. In 1892 Mackintosh met fellow artist Herbert McNair, who was to become his best friend and the impressive and independent artist Margaret Macdonald, who would soon become his wife.

The Immortals (c. 1894) portrait hangs on the wall of the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Scotland and depicts the group, "The Immortals", the most progressive artists and architects living in Glasgow at this time. Within is the smaller group, "The Four", which includes Mackintosh, McNair, and the Macdonald sisters.

Mature Period

In 1897 Honeyman and Keppie won the commission for the redesign for the Glasgow School of Art. Somewhat disappointingly however, at the opening ceremony for the building in 1899, Keppie was introduced as the architect responsible, despite the fact that this was mainly Mackintosh's achievement (and also happened to be his first major work). Understandably, Mackintosh felt the lack of appropriate credit somewhat acutely and mentioned to his friend and fellow designer, Hermann Muthesius, "I hope when brighter days come, I shall be able to work for myself entirely and claim my work as mine." Aside from his unacknowledged building projects, even Mackintosh's furniture designs were at first poorly received in his hometown of Glasgow. Luckily, his long-term supporter and teacher, Francis Newberry, sent these innovative designs to artists in Belgium where they were praised, a success that marked the beginning of Mackintosh's better reception on the continent. Such burgeoning connections across the channel eventually amounted to an invitation to make work for the 8th Secessionist Exhibition in Vienna (1900) and to include work in the International Exhibition of Decorative Arts in Turin (1902).

Mackintosh married Margaret Macdonald in 1900 and the couple moved into a flat at 120 Mains Street where they welcomed and hosted many artists visiting from mainland Europe. These early years of marriage were a time of peace and intense creativity; they never had children but took great joy in caring for the children of friends. Mackintosh's nieces and nephews were often visitors to the flat and it was here that they had their first tastes of many exquisite chocolates and sweets sent from Vienna. The flat was full of love, laughter, delicious cake - near a roaring fire. During this period, Mackintosh received some major private architectural commissions in and around Glasgow; including the design of a number of tea rooms for the business woman, Catherine Cranston, and the Hill House, which was to become the personal residence for publisher, Walter Blackie. He was given vast creative freedom on both of these projects, and the results were magnificent.

Mackintosh had met Catherine Cranston, a Glasgow entrepreneur, early in his career. Cranston was the daughter of a wealthy tea merchant and strongly believed in temperance. She derived the idea of creating a series of "art tea rooms" (not only a place to drink tea, but also a sanctuary where one could enjoy and ponder art), and as such, between 1896 and 1917, Mackintosh and Macdonald designed and re-styled all four of her Glasgow tea rooms. The Willow Tearooms is perhaps the most important of the four commissions because this was the only one for which Mackintosh had full control over all architectural and interior design details. The rooms were lavish, with different color schemes for men and women and a magnificent "Room Deluxe" which included one of Macdonald's most beautiful gesso panels.

In 1904, Mackintosh was offered a partnership at Honeyman and Keppie (he would no longer be only an employee, but a managing partner), and two years later the couple moved into their new home. This was the largest property that the Mackintoshes ever owned. They remained here from 1906 to 1914, and for the earlier years this was a highly inspired and creative time for the couple. Florentine Terrace was in the genteel West End suburb of Hillhead, which represented a move up the social ladder for Mackintosh. He had moved away from the grimy, industrial East End to an area with parks, a progressive art gallery, and the new location for the city's university. The couple made the dwelling much more open plan (common now but not at all at the time), and they had a garden and even electricity. Visitors described the house as "an oasis" and "a delight", but aside from his exciting work on the west wing of The Glasgow School of Art, work was not as fluid and easy to come by as it was when living in the Mains Street flat.

In 1907, Mackintosh's plans for the second half of the Glasgow School of Art were approved and subsequently completed in 1909. Inaccurately for the second time, John Keppie was credited as the lead architect on the project, "with assistance from Charles R Mackintosh". It was another difficult moment for Mackintosh; the year before his father had died of bronchitis aggravated by heart problems and at the same time he himself was suffering from depression, alcoholism, and bouts of pneumonia. Due to increasing anti-social behavior, Mackintosh was asked to leave the Keppie firm, signifying the end of an era, and also of his great contribution to the city of Glasgow.

Late Period

In the summer of 1914 Mackintosh and Macdonald moved to the rural, (so-called) artist haven of Walberswick, in Suffolk. Initially they enjoyed the new location, as they rediscovered drawing and worked on a series of botanical watercolors in close collaboration. Following the outbreak of World War I however, Mackintosh was briefly arrested under suspicion of being a German spy due to his extensive correspondence with Vienna and his unusual ways and mannerisms; he was soon released without charge but expelled from the town anyway because locals were not happy with his residence there. Shunned once again, the couple moved to London where Mackintosh became reclusive and found it extremely difficult to secure work. Whilst Macdonald socialized and enjoyed the city's highly active bohemian art scene, Mackintosh suffered from deteriorating mental health and felt the strains of financial struggle.

In search of sunshine and a lower cost of living, the couple moved to Port Vendres, a coastal town in the South of France in 1923. This new place and way of life imbued Mackintosh with happiness and reinvigorated his creative energies; he greatly enjoyed painting the surrounding landscape. Regrettably however, both Macdonald and Mackintosh began to suffer from ill health and were forced to return to London for medical treatment. Mackintosh had a cancerous growth on his tongue and had to have regular appointments at Westminster Hospital. Even though sick, and undergoing treatment, while at the hospital the dedicated artist helped students with their anatomical drawings and continued to draw prolifically himself, although at this point he had stopped signing his works. Mackintosh sadly lost his power of speech and reportedly died holding a pencil in his hand in 1928. There was a small ceremony at Golders Green crematorium, and while there was no notice in the Scottish press, The Times of London did appropriately acknowledge that "[t]he whole modern movement in Europe looks to him as one of its chief originators."

The Legacy of Charles Rennie Mackintosh

Mackintosh's career shines as a guiding light of modernist innovation. His work in many ways came before its time. Many modernists architects were interested in creating "machines for living" (such as Le Corbusier), whilst Mackintosh privileged a more serene homely environment that drew much from the design ideals of Japan. His forward-thinking minimal aesthetic is one that is now highly celebrated and sought after for home design in the early twenty-first century.

During the 1920s Mackintosh's work was considered quite unfashionable and not really worthy of critical evaluation. However, the more clear-sighted artists William Davidson and Randolph Schwabe requested to manage and care for the Mackintosh estate after his death. Subsequently, in 1933 Davidson co-curated the Mackintosh Memorial Exhibition at the McLellan Galleries. Then in 1952 the Victoria & Albert Museum importantly situated Mackintosh in context with his contemporaries in the "Victorian and Edwardian Decorative Arts" exhibition. As a generous act of patronage, Davidson bought Mackintosh's house in Florentine Terrace. Davidson lived in the house himself and it was then passed to his children, who gifted it to the University of Glasgow. The house was demolished in 1963, but since that time has been entirely re-built and furnished with Mackintosh's original furniture to become part of the Hunterian Art Gallery. As such "The Mackintosh House" stands as a visitor attraction bringing people from all over the world to Glasgow.

The 1960s saw a revival of interest in Art Nouveau, and as such led to a new appreciation of Mackintosh's work. By the 1970s, memory of the artist was fading in Glasgow as the tea rooms for which he had become most famous were rapidly disappearing. Appropriately however, in 1973 the Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society was founded in order to campaign for the conservation of his buildings and to better educate people to the significance of the artist's achievements. Simultaneously, in 1973 the Cassina design firm in Milan began to mass produce furniture in debt to Mackintosh's signature style (in particular his low-seated high-back chairs) and in 1975 his original works had started to set auction records at Sotheby's. In 2015 the new branch of the Victoria & Albert Museum in Dundee announced that they would be reconstructing one of Mackintosh's tea rooms within the gallery for display purposes.

Authorities on design history, Charlotte and Peter Fiell noted that "[a]s one of the founding fathers of organic Modernism, Charles Rennie Mackintosh left an important legacy that is extremely relevant to our own times - a holistic and humanistic approach to design that comprehends the world as a complex living organism and respects the personal, social, environmental and spiritual realities found within it." They also stated that "[w]hile the astonishing modernity of his work has long ensured him a place of prominence among the pioneers of the Modern Movement ... his promotion of symbolic decoration has been hailed as prophetically post-modern." Mackintosh's biographer Mark Cairney ruminates that "[h]ad his London schemes been built he would have predated Gropius and Le Corbusier by a decade."

Perhaps more accurate is to place Mackintosh alongside fellow architects who sought to make "artist homes", not so much urban masterworks; as such the American Frank Lloyd Wright, the British C.F.A. Voysey, and the fellow Scot M.H. Baillie Scott were all likely inspired by, as well as inspiring for, Mackintosh. This group of architects were not interested in making show-stopping pieces that cut into the landscape, but instead in creating organic buildings crafted from local materials that softly merged into their surroundings; for them, the smallest detail - such as a door handle - mattered as much as the impression of the whole.

Influences and Connections

- Norman Shaw

- CFA Voysey

![Margaret MacDonald]() Margaret MacDonald

Margaret MacDonald- Herbert McNair

- Francis Henry Newbery

- Frances McDonald

-

![Japonism]() Japonism

Japonism -

![Arts and Crafts Movement]() Arts and Crafts Movement

Arts and Crafts Movement - Scottish Baronial Architecture

-

![Walter Gropius]() Walter Gropius

Walter Gropius -

![Gustav Klimt]() Gustav Klimt

Gustav Klimt ![Josef Hoffmann]() Josef Hoffmann

Josef Hoffmann

![Margaret MacDonald]() Margaret MacDonald

Margaret MacDonald- Hermann Muthesius

Useful Resources on Charles Rennie Mackintosh

- The Quest for Charles Rennie MackintoshOur PickBy John Cairney

- Charles RennieBy Colin Baxter & John McKean

- Charles Rennie Mackintosh: The Architectural PapersEdited by Pamela Robertson

- The Chronycle: The Letters of Charles Rennie Mackintosh to Margaret MacDonald MackintoshEdited by Pamela Robertson