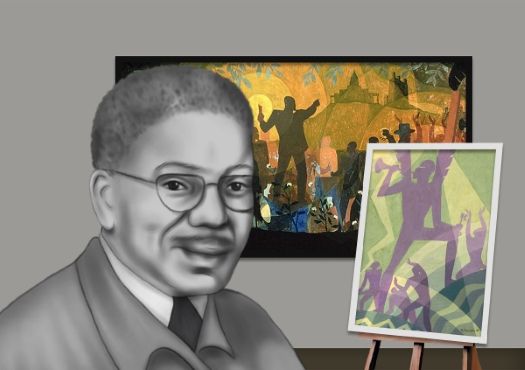

Summary of Aaron Douglas

In both his style and his subjects, Aaron Douglas revolutionized African-American art. A leader within the Harlem Renaissance, Douglas created a broad range of work that helped to shape this movement and bring it to national prominence. Through his collaborations, illustrations, and public murals, he established a method of combining elements of modern art and African culture to celebrate the African-American experience and call attention to racism and segregation.

Accomplishments

- Douglas depicted African subjects in an innovative and bold graphic style that was inspired by modern art, particularly Cubism. His approach elevated both everyday experiences and non-Western history to be part of an international avant-garde. He also integrated the rhythms of jazz into his compositions, adding an additional element of African-American culture to his imagery.

- Flattening his figures to two-dimensional silhouettes and generalizing their forms to be generic men and women, Douglas created imagery that celebrated African and African-American themes in terms that were universal and integrative. He employed this style across a range of different media, including painting, illustration, murals, and prints.

- Douglas often worked with a narrow range of colors, instead using compositional elements and shapes like concentric circles and radiating beams, to create dramatic focal points and dynamic movement. These abstract elements enhanced the narratives of his paintings to make them more emotionally impactful.

- Through his work with the Harlem Artists Guild and as the chair of the art department at Fisk University (a historically Black college), Douglas worked to increase educational access and career opportunities for young African-American artists. He was an important mentor for second-generation Harlem Renaissance artists and an inspiration to contemporary artists who deal with race and identity in their work.

Important Art by Aaron Douglas

Sahdji (Tribal Women)

This illustration, one of Douglas's earliest known works, was created under the tutelage of German artist Fritz Winold Reiss, who encouraged Douglas to draw inspiration from African art and culture, as well as elements of Art Deco, Art Nouveau, and Cubism. We can see Douglas experimenting with all of these influences in this piece. From African Art, we see him using a distinctly Egyptian style, with silhouetted, composite figures in profile arranged in rows. Douglas said of the image, "I used the Egyptian form, that is to say, the head was in profile flat view, the body, shoulders down to the waist turned half way, the legs were also done in a broad perspective . . . the only thing that I did that was not specifically taken from the Egyptians was an eye." From Art Deco and Art Nouveau, he borrowed bold, angular forms that are abstracted to create an overall sense of symmetry and balance. The fragmented space and lack of single-point perspective reveal the influence of Cubism. Douglas would continue to develop these key elements to create his signature style in future works.

This black and white image combines figurative and decorative elements. At the top left, the sun has been graphically simplified as a partial circle with thick, wavy lines emanating outward. The series of bold, triangular forms suggest mountains or pyramids as part of a geometric landscape. At the center of the image stands a large, solid Black silhouetted female figure with one hand raised, a pose echoed in the three repeating smaller female figures who are arranged in a row. Their bodies are contorted in a wave-like posture, indicating that they may be engaged in some sort of dance. This rhythmic quality is carried over to the bottom and right side of the image, where several more geometric shapes and patterns appear, including repeating wavy lines and jagged black forms.

Throughout his career, Douglas was interested in the representation of black women. Writing to his wife in 1925 (the same year that this work was created) he explained, "We are possessed, you know, with the idea that it is necessary to be white, to be beautiful. Nine times out of ten it is just the reverse. It takes lots of training or a tremendous effort to down the idea that thin lips and straight nose is the apogee of beauty. But once free you can look back with a sigh of relief and wonder how anyone could be so deluded." In this image, he attempts to create a visual vocabulary for Black beauty, emphasizing the female figures' curvaceous bodies, thick lips, and African-American profile.

Ink and graphite on wove paper

The Judgment Day (Illustration for God's Trombones by James Weldon Johnson)

Douglas was commissioned to create a series of illustrations for James Weldon Johnson's book of poetry God's Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse. Although he considered himself agnostic, Johnson wished to pay respect to the Black Christian preachers and religious tradition that had been important during his youth. The illustration seen here was made for the last poem in the book, titled "The Judgment Day." The following is an excerpt from that poem:

Oh-o-oh, sinner,

Where will you stand,

In that great day when God's a-going to rain down fire?

Oh, you gambling man - where will you stand?

You whore-mongering man - where will you stand?

Liars and backsliders - where will you stand,

In that great day when God's a-going to rain down fire?

Douglas's illustration is comprised of overlapping black silhouette figures and black and white geometric shapes of varying opacities. The largest figure (meant to represent the angel Gabriel playing his silver trumpet to herald the end of times) stands with one foot perched upon a quarter-circle geometricized mountain and the other foot resting on a curved shape bisected by a zig-zagging line that is meant to represent the sea. The smaller figures to either side of Gabriel represent mankind. The saved (indicated by the figure on the right with his hands raised) await entrance into heaven, while the sinners on the left side topple downward to eternal damnation in hell. A large bolt of lightning strikes one of the sinners on the left side, while a beam of light, representing enlightenment, shines down on the saved figure on the right. By depicting black figures in recognizable biblical scenes (which at the time was quite innovative) Douglas sought to demonstrate to African-Americans that they were God's children just as much as white people.

The geometric style adopted by Douglas for this illustration reveals the influence of European Art Deco posters, and his use of separate color fields in lieu of outlines indicates the influence of Cubism. These choices, however, may likely have been as much pragmatic than stylistic, as they allowed him to reduce the number of colors used in the image, which lowered publication costs. Moreover, by simplifying his images in such a way, he allowed for the message of his work to be read by anyone, even children. In an early review of God's Trombones, the Topeka State Journal wrote "These illustrations are remarkable for their originality, their poetry of conception and their appropriateness to the text. They stamp Mr. Douglas as one of the coming American artists."'

English professor Robert O'Meally sees Douglas's use of geometric shapes as deriving from the influence of Harlem Renaissance jazz (in particular the music of Douglas's friend Duke Ellington). For instance, O'Meally asserts that the concentric circles "may have been inspired by the new technology of the audio-recording," as they mimic the form of vinyl records. Moreover, the various geometric shapes used by Douglas create a sense of "rhythmical repetition [which] gives them a natural and supernatural aspect, and underscores their sense of musicality". The combination of both smooth and jagged forms in Douglas's work may be read as an embodiment of jazz music, which, according to O'Meally, is "...a classic sound, one as multifaceted and pristine as a diamond," which simultaneously has "graininess and grumble." This point of view is seconded by arts professors Deborah Johnson and Wendy Oliver who write, "The only other influence on Douglas that featured as significantly as Africa was jazz, and he both wrote about and painted the jazz musician as a kind of modern African American messiah." Music and jazz would continue to be integral aspects of Douglas' works, such as in Song of the Towers (from the series Aspects of Negro Life, 1934).

Illustration

Harriet Tubman

This painting, completed in a palette of greens and blues, showcases Douglas's mature style. At the center is the silhouetted female figure of Harriet Tubman, who freed over 400 slaves through her work with the Underground Railroad. Rendered in a dark shade of green atop the lightest portion of the painting, she provides a focal point for the viewer as her arms stretch upwards, revealing a broken set of shackles. Just below her sits a cannon, wafting smoke directly to her right, and a kneeling figure with his hands shackled together, who looks up at her. Behind this figure is another kneeling form, bent over with his head and hands on the ground. Several other figures are seen in the background, carrying large loads (likely sacks of cotton) on their heads and backs. This is in contrast to the area to the right of Tubman, where several more figures (men, women, and children) appear kneeling, standing, and sitting, with one of them reading a book, and another holding a hoe. At the far-right side of the image stand tall towers, reminiscent of modern skyscrapers. The image has been overlaid with Douglas's signature radiating circles and a beam of light. The central point of the concentric circles is focused on the muzzle of the smoking cannon, while the light shines down on Tubman from the top of the frame.

This painting can be read from left-to-right as a narrative about past, present, and future, starting with slavery and bondage (the shackled, toiling figures), moving through the efforts of abolitionists (like Tubman), the civil war and emancipation (the cannon, and the broken chains held by Tubman), and ending on the right-hand side with opportunities and accomplishments. Douglas highlights access to education (the reading figure), being able to remain with, and provide for, one's family (the woman and child), freedom to farm independently and benefit directly from one's own labor (the figure holding the hoe), freedom to enjoy leisure time (the man relaxing on his back), and freedom to relocate to urban centers and build lives and communities there (the towers).

With this narrative, Douglas offered "New Negroes" a collective narrative by which they could define themselves, their origins, their futures, and perhaps even their own version of the American dream. A central aspect that he emphasized was the new self-determination of African-Americans, which stands in sharp contrast to previous depictions that were made for white audiences, showing African-Americans as dependent on white society. While this sense of self-determination and defiance is shown, in part, through Tubman's strong body language, he focuses more on the broader efforts made to liberate slaves in the American South, rather than just on Tubman as a heroic figure. This is why the concentric circles focus on the cannon, rather than Tubman. That this work was commissioned for the Bennett College for Women may have influenced Douglas's choice to also highlight Tubman.

Oil on canvas - Bennet College Art Gallery, Greensboro, North Carolina

The Negro in an African Setting (From the Series Aspects of Negro Life)

In 1934, Douglas was commissioned to create a series of four murals for the 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library, funded by the Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project. The series was titled Aspects of Negro Life, and the four murals include The Negro In An African Setting, An Idyll of the Deep South, From Slavery Through Reconstruction, and Song of the Towers. Each of the murals depicts a different aspect of African-American cultural history, from its roots in Africa, through the era of slavery, Emancipation, post-Reconstruction, and the Great Migration north.

This mural, The Negro in an African Setting, represents pre-slavery life in Africa as vibrant and joyous. Douglas depicts a large group of Africans, holding spears and bows, in circular formation around two individuals engaged in a sort of ritual or dance. These two central individuals are tilted backwards at a steep angle, creating a more dynamic sensation that captures Douglas's view of African spirituality more than any specific African dance, which typically would pitch the dancers forward. The lushness the African wilderness is indicated by the repeated foliage in and around the group. Concentric circles of varying opacity indicate motion and energy, while simultaneously focusing the viewer's attention on a small, totem-like "fetish" figure, emphasizing the importance of spirituality to the African people. The cultural historian Glenn Jordan asserts that "The image evokes a sense of community, spirituality, sovereignty and self-determination," which exemplifies the African-American imaginative construct of African life prior to European interference.

Douglas said of the image "The first of the four panels reveals the Negro in an African setting and emphasizes the strongly rhythmic arts of music, the dance, and sculpture, which have influenced the modern world possibly more profoundly than any other phase of African life. The fetish, the drummer, the dancers, in the formal language of space and color, create the exhilaration, the ecstasy, the rhythmic pulsation of life in ancient Africa." The work was controversial, however, with many of Douglas's contemporaries accusing him of playing into racism, employing all the popular tropes that suggested a primitive existence. Black art historian James A. Porter called Douglas's paintings "tasteless" and "reminiscent of minstrel stereotypes." His defenders pointed out that Douglas's murals were not intended for a white audience that was passively consuming African culture, but rather at "a Black audience many of them New Negroes or New Negroes-in-the-making, who are interested in Africa as part of a quest for dignity, pride and 'self-awareness'".

Oil on canvas - Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture

An Idyll of the Deep South (From the series Aspects of Negro Life)

This work forms the second of four murals that Douglas created for the135th Street branch of the New York Public Library, commissioned through the Works Progress Administration. The image shows several African-Americans in a natural setting, with trees punctuating the picture plane and foliage above. Unlike the title suggests, however, this is no idyll but a scene of tragedy and forced labor.

A group of African-Americans sit at the center, playing musical instruments. A series of concentric circles draws the viewer's eye to these figures, a technique that Douglas often used to indicate movement and energy. To either side, he depicts the violence and struggle of slave life. On the far left, figures kneel on the ground, perhaps weeping or praying, gathered around a rope hanging from a tree that references the practice of lynching. At the far right, several slaves obscured in darkness hold hoes and work the earth. A small, white, five-pointed star at the upper-right corner of the image shines a beam of light down diagonally across the image.

With this work, Douglas critiqued the stereotypical notion of the "happy Southern plantation Negro," flanking the central group of musicians with scenes of harsh, historical reality. At the same time, Douglas's symbolism remains open-ended and allows for multiple levels of interpretation. For example, the star in the image was typically understood to represent the Underground Railroad's well-known directive to "follow the North Star" to freedom. However, in an April 1971 conversation with artist David C. Driskell at Fisk University's Fine Arts Festival, Douglas revealed that he actually meant it to represent the "the red star of Russia," referencing the belief among some Harlem intellectuals that true equality might be reached through the "alternative policies of communism and socialism." The way that the star's light shines directly on the group of musicians can also be read as a reference to the importance of Christianity (frequently embodied in slave music) as an important glimmer of hope in the lives of slaves.

Oil on Canvas - Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at The New York Public Library

Defiance (From the series Emperor Jones)

This woodblock print was part of a commission to illustrate Eugene O'Neill's 1920 play Emperor Jones. The play tells the story of an African-American, Brutus Jones, who is imprisoned for killing another B man during a dice game before escaping to an island in the Caribbean where he establishes himself as a tyrannical emperor. The play was meant as a commentary on the U.S. occupation of Haiti, which began in 1915 and lasted until 1934.

The play won a Pulitzer prize, and is notable for being the first Broadway play with an African-American actor (Charles Gilpin) in a lead role, particularly as he performed a complicated psychological character that did not rely on bigoted stereotypes of black people. When the role was recast in 1925, it launched the career of Douglas's friend, the actor/singer Paul Robeson. Robeson would star in the 1933 film version, as well.

Douglas completed four black-and-white woodblock images representing his interpretation of the story. This print, Defiance, shows Jones in a military uniform with an aggressive, wide-legged stance and a confrontational expression. He wields a whip that overlaps with several leaves of lush foliage. Below him, wavy lines of alternating black and white, overlaid with fish, suggest a river. While these landscape elements indicate the setting in the Caribbean jungle, the stark contrast of black and white enhances the sense of drama. The monochromatic patterning also reads as rhythmic, alluding to drum beat which continuously accelerates over the course of the play.

Woodblock print - David C. Driskell Center

Biography of Aaron Douglas

Childhood

Aaron Douglas was born into a rather large, proud, and politically active African American community in Topeka, Kansas. His father worked as a baker, and while his family did not have much money, his parents emphasized the importance of education and aimed to instill a sense of optimism and self-confidence in their son. Douglas's mother, Elizabeth, enjoyed drawing and painting watercolors, a passion she shared with her son. Early in his life, he decided that he wanted to become an artist.

After graduating from Topeka High School in 1917, Douglas wanted to attend university, but was unable to afford tuition. He decided to travel east with a friend, working briefly in Detroit at the Cadillac plant. He later recalled that he was the target of racism and discrimination, always given the worst, dirtiest jobs at the plant. In his free time, he attended evening art classes at the Detroit Museum of Art

Education and Early Training

Douglas went on to attend the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, where he earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in 1922. During his time at college, he also worked as a waiter, and was an active member of the University Arts Club.

After graduation, Douglas spent two years (1922-1923) at Lincoln High School in Kansas City, Missouri (where he taught classes in drawing, painting, stenciling, and batik). He also served as a mentor to the Art Club and was one of only two black teachers in the school. He said of Kansas City "I can't live here. I can't grow here. [This] is not the way the world is. There are other places where I can try to be what I believe I can be, where I can achieve free from the petty irritations of color restrictions. I've got to go, even if I have to sweep floors for a living." In June 1925, he fulfilled his dream of moving to New York City. Douglas quickly became immersed in the thriving art and culture scene in Harlem, recalling that "There are so many things that I had seen for the first time, so many impressions I was getting. One was that of seeing a big city that was entirely black, from beginning to end you were impressed by the fact that black people were in charge of things and here was a black city and here was a situation that was eventually to be the center for the great in American Culture."

Shortly after his arrival, Douglas won a scholarship to study with German-born artist/illustrator Winold Reiss who was known for his Romantic and idealized portraits of Native Americans and African Americans. Reiss's work also drew from popular and commercial sources such as German folk paper-cuts (scherenschnitt) an influence that would impact Douglas's work. Reiss also encouraged Douglas to turn to his African heritage for artistic inspiration.

Douglas soon developed his signature style characterized by elegant, rhythmic silhouettes. His first illustration commissions were for the National Urban League's magazine, The Crisis, and the National Association for the Advancement Colored People's magazine Opportunity. In these early works, he created powerful images of the struggles of marginalized people. He won several awards for his illustrations. He then received a commission to illustrate an anthology of philosopher Alain LeRoy Locke's highly influential work, The New Negro (1925). The success of this book prompted requests for illustrations from other Harlem Renaissance writers. He also created illustrations for popular magazines such as Harper's and Vanity Fair.

In 1926, Douglas co-founded Fire!! A Quarterly Journal Devoted to the Younger Negro Artists along with novelist Wallace Thurman. The magazine's aim was "to express ourselves freely and independently - without interference from old heads, white or Negro," and "to burn up a lot of the old, dead conventional Negro-white ideas of the past ... into a realization of the existence of the younger Negro writers and artists, and provide us with an outlet for publication." It tackled a range of controversial issues and was condemned by many within the Harlem Renaissance for promoting stereotypes and vernacular language. With poor reviews by both Black and White audiences, Fire!! only published one edition.

On June 18, 1926, Douglas married Alta Sawyer, a teacher. The two had met in 1917, however Sawyer had married another man immediately after graduating from high school. Between 1923-1925, while still married, she began corresponding regularly with Douglas. Eventually she divorced her first husband in 1925. Speaking in 1968, ten years after her sudden passing, Douglas stated that she "became the most dynamic force in my life, my inspiration, my encouragement." The couple lived on Edgecombe Avenue in Harlem.

In 1928, Douglas received financial support from a wealthy septuagenarian named Charlotte Mason, the widow of a prominent New York surgeon. Mason provided support to a number of artists and writers of the Harlem Renaissance, although her views of African Americans as more "primitive" and therefore primal and spiritual, troubled several of her beneficiaries, including Douglas. When she told Douglas that she believed that his art education had a deleterious effect on his natural instincts, he ended their relationship.

Also in 1928, Douglas and fellow artist Gwendolyn Bennett received fellowships to study at Dr. Albert C. Barnes's collection of modern and African art in Merion, Pennsylvania. A physician and pharmaceutical inventor, Barnes was also an avid art collector; he amassed an impressive collection of more than 120 works of African art, primarily from Mali, Ivory Coast, Gabon, and the Congo. Barnes's collection featured ceremonial masks and domestic objects such as drinking vessels and furniture. His presentation of these artifacts as artworks, rather than ethnographic curiosities, was unusual for the time.

Mature Period

During the 1930s, Douglas's career began to gain momentum as he became a prominent member of the Harlem Renaissance. In 1930, Douglas served as artist in residence at Fisk University in Nashville, where he was commissioned to paint a cycle of murals for the Cravath Memorial Library. (He would later return to Fisk and become a long-time member of its faculty.)

The following year, he travelled to Paris, where he studied at the Académie Scandinave, and befriended sculptor Charles Despiau and Fauvist painter Othon Friesz. He returned to New York in July of 1932, moving into the Sugar Hill area of Harlem.

In 1935, Douglas helped to form, and became the first president of, the Harlem Artists Guild, along with sculptor Augusta Savage, the painter, sculptor, illustrator, and muralist Charles Alston, muralist Elba Lightfoot, and writer Arthur Schomburg. (Later members included Romare Bearden, Gwendolyn Bennett, and Norman Lewis.) The guild aimed to support and promote young African-American artists, with special focus on work that would improve public understanding of issues faced by the African-American community, including racism, unemployment, and poverty. The guild also successfully pressured the Works Progress Administration to improve opportunities for African-American artists.

Douglas came to be known as a central figure in the Harlem Renaissance (1918-1937). This artistic and literary movement was part of the larger "New Negro" movement, during which national organizations were founded to promote civil rights, efforts were made to improve socioeconomic opportunities for African-Americans, and artists worked to define and depict African-American heritage and culture for themselves, offering a counter-narrative to stereotypical racist representations. This movement came about as a result of several converging factors: retaliation against White dominance and racial violence, mass migration of African-Americans from rural areas to urban centers, and increased militancy as well as national pride on the part of African Americans who participated in the First World War.

Late Period

In 1937, Douglas received a Julius Rosenwald Foundation fellowship to travel to historically-Black colleges in the South. The Foundation had been created in 1917 by Chicago businessman Julius Rosenwald, who made his fortune as part owner, president, and chief executive of Sears, Roebuck & Company. Rosenwald funded the building of more than 5,000 schools for Black students in the South, and also provided stipends to hundreds of African-American artists, writers, and scholars. In 1938, Douglas was awarded a second Rosenwald Fellowship, this time to paint in Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and the Virgin Islands.

In 1939, Charles S. Johnson, the first African-American president of Fisk University, invited Douglas to develop the art department at the university. Douglas served as department head until his retirement in 1966. To better serve in this capacity, Douglas enrolled in the Teacher's College at Columbia University (New York) and earned his Master's degree in Art Education in 1944. He also helped to establish the Carl Van Vechten Gallery at Fisk University, and was instrumental in obtaining important pieces for its collection, including works by Winold Reiss and Alfred Stieglitz. Artist and professor Sharif Bey asserts that Douglas "had a profound influence on this era of art education in the segregated South [by] expand[ing] learning opportunities through networks and exhibition programming that challenged racial subjugation."

In this later part of his life, Douglas maintained dual residences in Nashville, where he was working at Fisk University, and in New York, so that he could regularly attend lectures and exhibitions. In addition to educating others, Douglas also continued to be an active learner well into adulthood, enrolling in courses on printmaking and enameling at the Brooklyn Museum Art School in 1955.

In 1963, President John F. Kennedy invited Douglas to the White House to attend a celebration of the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation. In 1973, seven years after retiring, he was awarded an honorary doctorate from Fisk University. He continued to guest lecture until his death.

Douglas died of a pulmonary embolism on February 2, 1979.

The Legacy of Aaron Douglas

Douglas is sometimes referred to as "the father of Black American art," as he was a central figure in the development of an artistic vocabulary that generations of African-American artists would use to present their culture and identity on their own terms and to combat popular, racist depictions of African Americans. Douglas developed this vocabulary from a combination of modernist and African elements. Art history professor David C. Driskell said that it was Douglas "who actually took the iconography of African art and gave it a perspective which was readily accepted into Black American culture. His theory was that the ancestral arts of Africa were relevant, meaningful and above all a part of our heritage, and we should use them to project ourselves." Similarly, writer Alain Locke described Douglas as "the pioneer of the African style among the American Negro artists, having gone directly to African motifs since 1925."

Douglas's stylistic elements would influence other African-American (and African-Canadian) artists who aimed to affirm Black identity in their works. For instance, his use of bold, solid fields of color, a strategy learned from print media, and his interest in making African-American history accessible, can be seen in the work of fellow Harlem Renaissance painter Jacob Lawrence and in the work of Douglas's own student, Viola Burley Leak. His desire to create a distinct form of African-American artistic expression influenced the AfriCOBRA artists of the 1960s and 1970s. His use of silhouettes and paper cut-outs can be seen in the work of the present-day African-American artist Kara Walker, who also aims to depict issues of racism and Black struggle in her work. And his use of Egyptian artistic elements, as well as his preoccupation with presenting Black female beauty, can also be seen in the work of the present-day, Montreal-born artist, Uchenna Edeh.

Influences and Connections

![Othon Friesz]() Othon Friesz

Othon Friesz- Winold Reiss

- Charles Despiau

- W.E.B. Dubois

- Alain Locke

- Langston Hughes

-

![Jacob Lawrence]() Jacob Lawrence

Jacob Lawrence -

![Kara Walker]() Kara Walker

Kara Walker - Viola Burley Leak

- Uchenna Edeh

- W.E.B. Dubois

- Alain Locke

- Langston Hughes

Useful Resources on Aaron Douglas

- Aaron Douglas: Art, Race, and the Harlem RenaissanceOur PickBy Amy Kirschke

- Aaron Douglas and Alta Sawyer Douglas Love Letters from the Harlem RenaissanceBy The Aaron and Alta Sawyer Douglas Foundation