Summary of Maurice de Vlaminck

French Fauve artist, Maurice de Vlaminck, seems to have been in a contest with the iconic Cubist, legendary womanizer, and notoriously egotistical, Pablo Picasso. What these two rebellious artists did have in common was an uncanny ability to innovate, to create something completely new. For Picasso, it was Cubism; for Vlaminck and his fellow Fauves, André Derain and Henri Matisse, it was the bright, expressive colors - likened to "fire crackers" - and outrageously unconventional depictions that earned the group their influential place in history. Vlaminck later railed against developments in modern art when, ironically, he was one of the true pioneers of modernist abstraction.

Accomplishments

- Vlaminck, along with the other Fauve painters, continued the approach established by the Impressionists of rejecting conventional themes and instead representing scenes from everyday life. Rather than depicting stories from mythology, history, or portraying notable figures, his paintings often featured unremarkable cityscapes and landscapes, as well as unknown denizens of Parisian nightlife, all enlivened by his bright, unnatural Fauve palette.

- Even though he experimented with the Cubist style, Vlaminck seems to have regarded Cubism as an unworthy opponent of what he saw as the more revolutionary artistic style of the Fauves. He alienated himself from the Paris art world by his outspoken condemnation not only of Cubism, but of its most renowned co-founder, Picasso.

- Vlaminck's particular brand of Fauvism incorporated heavy, dark outlining of brightly colored forms that - more so than those of the other Fauves - had a profound impact on the development of abstract, expressive painting and printmaking on German modernist artists like Wassily Kandinsky, Ernst Kirchner, and Emile Nolde.

Important Art by Maurice de Vlaminck

At the Bar

Vlaminck paints a satirical caricature of a woman sitting at a bar as a means of exposing the problem of prostitution and alcoholism in capitalist society. He may have been influenced by Toulouse-Lautrec's portrayal of prostitutes and solitary drinkers, however, he claimed that it was not his goal to convey the sitter's psychology. Although the woman is staring out at the viewer, her gaze is blank, detached. Rather than avoiding creating a psychological portrait, Vlaminck has succeeded in lending the woman, with her vapid stare, a stark and tragic demeanor. The figure dominates the canvas; she is thrust to the foreground in which her massive drink rests, forcing the viewer to candidly engage with her as might well be the case with a heavily inebriated person.

The woman's messy hair and worn clothes suggest that she is part of the working class. Her reddish nose is visual shorthand for alcoholism, which is emphasized by the oversized red glass on the bar. The rough brushwork and rudimentary modeling are just as suggestive of the artist's perception of his subject as they are descriptive of her actual appearance. The artist offsets the depressing mood of the painting by somewhat salaciously mocking the sitter's oversized breasts to represent the last two zeros in the year that it was completed, 1900. The lurid colors of the figure contrast sharply with the dark background in which a street lamp seems to offer little protection from the hazards of the night.

Oil on canvas - Musée Calvet, Avignon France

Reclining Nude

Another of Vlaminck's works that explore the world of prostitution and dancehall entertainers, Reclining Nude represents a modern take on a classical subject: the female nude. He paints his subject using vibrant, unnatural colors and accentuates her features by way of colorful, overdone cosmetics creating a mask-like visage. The body is heavily outlined and simplified to the point where it is basically an amalgam of abstract shapes. The curving outline of the figure mimics the swirls of colored drapery in the background, lending the composition a decorative effect. The artist creates depth and volume by building the surface of the canvas up with his use of flat passages of thickly applied paint.

Like Manet's Olympia (1863), also a prostitute, Vlaminck represents the sexual encounter she offers as a commodity. Like her counterpart in the Manet painting, Vlaminck's reclining nude confronts the viewer with her powerful, unwavering gaze. Unlike a traditional, idealized nude female, this unknown woman is meant to represent a boldly naked, unquestionably modern woman. One hand grasps an article of clothing that she has recently removed, further emphasizing the process of seduction. Like Manet and Derain, Vlaminck attempts to represent the "splendor and misery" of capitalism in modern life - specifically, the reality of modern life for working class women. While Vlaminck's nude is grotesque; quite likely, he intended for the viewer to understand that the woman has contracted and is suffering from syphilis, thus the "misery" component of the piece, he makes the work less overtly bleak by using bright, almost celebratory colors - the consummate Fauve palette.

Oil on canvas - Museum of Fine Arts Houston

Houses at Chatou

Vlaminck lived and worked for over a decade in the small town, Chatou. This painting captures a view from the Île de Chatou in the Seine river, which also runs through Paris. The view is framed by two trees, a conventional device of landscape painting. Despite the bright colors that dominate the picture, the bands of darker tones mixed with white in the sky suggest that a storm is moving in. The absence of people in the painting conveys the sense of isolation and loneliness regular inhabitants of the popular tourist site may have experienced after the vacation season ended. Unlike his Impressionist predecessors, Vlaminck does not celebrate the culture of leisure.

Characteristic of the Fauve style, Vlaminck refrains from producing realistically rendered shadows and instead uses complementary colors to suggest an essentially deserted town on a quiet autumn afternoon. His lively, linear brushwork creates a sort of rhythmic pattern across the canvas. The minimal visual descriptions of objects, whether houses, trees, river, or clouds, provides this landscape with a kind of abstract simplicity made less serene by the swirls of color and twisting trees, which are indicative of the strong influence of van Gogh. Indeed, after seeing van Gogh's retrospective in 1901, Vlaminck was deeply inspired by the artist and declared, "I loved van Gogh that day better than my own father!"

Oil on canvas - The Art Institute of Chicago

Under the Bridge at Bezons (Under the Bridge at Chatou)

This landscape painting represents a view from the riverbank looking toward a bridge at Bezons between Chatou and Argenteuil. Vlaminck combines natural elements with the man-made monument, which seems to merge with the houses on the opposite side of the river. The artist's viewpoint is from the river's edge looking toward the underside of the bridge as though all he sees is off limits to him. Rather than a point of access to the city across the river, the bridge reads as an obstacle - or, alternatively, a protective barrier. Whereas the manmade elements of the composition are described in long brushstrokes or solid areas of color, the natural elements, the water, riverbank, and sky come together in a collection of short, staccato dashes of pigment reminiscent of Pointillism. Vlaminck uses vibrant colors contrasted with black to create the dramatic contrast one sees with the intense light of a bright summer afternoon.

Art historian John Klein suggests that Vlaminck based many of his paintings of Chatou and other nearby towns on views derived from souvenir postcards. Klein suggests that this composition, among others, is quite similar to a popular postcard of the riverbank at Le Pecq, which was on the other side of the bend in the Seine River from Chatou. The artist preserves the scenic elements of this leisure destination but refrains from depicting human activity. It is possible that, argues Klein, Vlaminck "may have felt estranged from many of the temporary middle-class inhabitants and the supporting labor that served them." Perhaps in keeping with Matisse's idyllic scenes that are more evocative of an ancient past than of the present, the artist refrained from referencing modern life; instead, he created a timeless image, which is at once stylistically modern and thematically nostalgic.

Oil on canvas - The Evelyn Sharp Collection

The Dancer from the Rat Mort

This work, a representation of a dancer at a bohemian Parisian nightclub called Le Rat Mort (The Dead Rat), seems to elude categorization as a portrait. So generic and simplified are the features of the sitter that it would be something of a leap to assert that Vlaminck was depicting a specific woman. The large eyes exaggerate the effect of the gaze with which this anonymous cabaret performer boldly confronts the viewer. The heavy cosmetics suggest garish excess rather than beauty or vanity.

The figure sits among a dappled surface of wild color as the patterning of her dress seems to merge with the background and this mixing of foreground and background has the effect of flattening the composition. According to art historian Tamar Garb, Vlaminck's painting (and others like it) constitutes "the end of painted portraiture," while also laying "the ground for its resurgence." Garb contends that the Fauves transformed the traditional genre of portraiture and created a more artificial, generalized representation of the human figure.

According to art historian Carol Duncan, the Fauves' unconventional style and themes were reflective of their anarchist sentiments. Their aim was to subvert the established political and economic order and liberate the working class. However, argues Duncan, in their attempt to romanticize the working class they represented their models - many of them actual prostitutes - as "possessions of the artist" and "objects of his particular gratification." While their anarchist rhetoric promoted liberation for the marginalized, rather ironically, the gender and class differences that are often represented in their works, whether deliberately or not, are in keeping with the hierarchy of sex and class in early-20th-century French capitalist, patriarchal society.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

Opium

Although Vlaminck later railed against Cubism, this painting suggests that he was interested enough in the style to experiment with it. He represents a seated woman clutching an elongated opium pipe in her left hand. The artists breaks apart the composition, converting the various elements of the picture into discrete geometric forms and nearly merging the figure with the background. The multiple, fragmented planes have a distinctly vertical orientation and appear almost to slide up and down in the composition. Also in keeping with Cubism, individual forms are constructed so that they appear to be visible from angles other than the primary vantage point. This composition is much more monochromatic, a radical departure from the bright Fauvist palette.

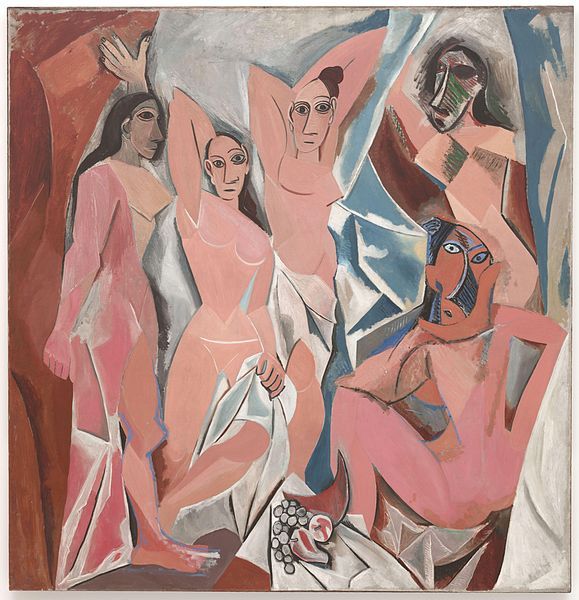

The figure's expressive facial features are reminiscent of the primitive tribal sculptures and African masks Vlaminck purchased in 1902, influencing the Cubist movement and the artists associated with it. Like Picasso, the artist used the masks to communicate a kind of debased sexuality of the other - in this case, prostitutes and drug addicts. Vlaminck, like many of his fellow avant-garde artists, once again engages with the theme of prostitution and brothel life. The exotic masks and sexualized sculptures representing are stand-ins for the women the artists objectified in their work.

Oil on canvas - Dublin City Gallery, Dublin Ireland

Marine

Vlaminck's late painting, Marine, features a violent seascape in which equal prominence is given to the sea and sky. The artist eschewed the bright, simplified abstraction of the Fauve style in his later career, adopting a more conservative and limited palette and naturalistic style. The brushwork is quite masterful and expressionistic, communicating directly the intensity of the windswept sea and sky. The dramatic contrast of light and dark tones and the theme itself calls to mind the Romantic seascapes of J.M.W. Turner. While Vlaminck claimed to have avoided museums, he may have seen Turner's work in London during his brief stay in 1911.

Vlaminck's later work is possibly even more reflective of the influence of Cézanne in terms of the more naturalistic palette and the use of Cézanne's distinctive technique known as "passage" that links individual forms to one another via leaks of color from one area to the next. It is as though, as he matured, Vlaminck's artistic tastes became more regressive, linking him not only with Cézanne but with his predecessors, modernist innovators like Manet and Courbet.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

Biography of Maurice de Vlaminck

Childhood

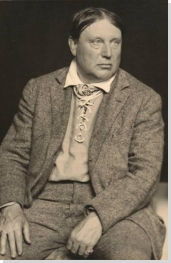

Maurice de Vlaminck was born on April 4, 1876 in Paris. He grew up in a working class family of musicians. His father Edmond Julien taught the violin, and his mother Joséphine Caroline Grillet taught piano. When he was three years old his family moved to Le Vesinet, a town about 10 miles northwest of Paris, to live with his grandmother.

Early Training

Vlaminck did not originally pursue a career as a professional artist. He said, "The thought of becoming a painter never as much as occurred to me. I would have laughed out loud if someone had suggested that I choose painting as a career. To be a painter is not a business, no more than to be an artist, lover, racer, dreamer, or prizefighter. It is a gift of Nature, a gift..." While he did not set out to be an artist, his education did include painting lessons from an academic artists between 1888 and 1891. Additionally, he studied with a local painter named Henri Rigalon in 1893. He held multiple careers to support his family before deciding to dedicate his life to painting.

Vlaminck had a reputation as a loudmouth, troublemaker, and womanizer. For instance, he is known to have frequented brothels in Paris. Despite his scandalous reputation, he married Suzanne Berly in 1894. They started a family less than a year later and had three daughters together.

Vlaminck was tall and powerfully built and sometimes supplemented his income with amateur boxing. His athletic prowess helped him succeed as a professional racer in 1893, when cycling became popular. He once confided on the subject, "The admiring looks of the girls and women, the bravos and cheers of the excited spectators... never, anywhere, had I felt such utter and complete satisfaction as I did in the days when I was nothing more than the winner of a simple bicycle race. At the time women admired us in the same way as today they admire an airman."

In 1896 Vlaminck contracted typhoid fever, dramatically halting his cycling career. Following his recovery, he was called upon for military service and served as a member of the regimental band. He found little time to paint while in the army and his earliest known work is a decoration for the regimental fête in 1899. During his service Vlaminck contributed multiple articles to radical magazines such as Fin de siècle and L'anarchie.

Vlaminck completed his military service in 1900. That same year, he met André Derain on a train after they were both involved in a minor railcar accident. The two immediately became close friends and collaborators although Derain's parents disliked their son spending time with a "bohemian anarchist." Vlaminck was banned from the Derain household, and allegedly, Derain would hang his paintings out of his window for Vlaminck to see and critique. They eventually rented a studio together in Chatou, which they maintained for a couple of years. Between 1902 and 1903 Vlaminck wrote pornographic novels that Derain illustrated. He began painting during the day and giving violin lessons in the evening, and performing with musical bands at night to scrape together an income.

Vlaminck once described how he and Derain painted together: (the story may well be apocryphal or at least exaggerated) "Each of us set up his easel, Derain facing Chatou, with the bridge and steeple in front of him, myself to one side, attracted by the poplars. Naturally I finished first. I walked over to Derain holding my canvas against my legs so that he couldn't see it. I looked at his picture. Solid, skillful, powerful, already a Derain. 'What about yours?' he said. I spun my canvas around. Derain looked at it in silence for a minute, nodded his head and declared, 'Very fine.' That was the starting point of all Fauvism."

Mature Period

While Derain and Vlaminck were already painting in the Fauvist style, it was Matisse who encouraged them to exhibit with him in 1905 at the Salon des Indépendents. Vlaminck met Matisse for the first time in 1901 during the van Gogh retrospective at the Galeries Bernheim Jeune in Paris. However, he did not see him again until Derain returned from his military service and invited Matisse to their studio in Chatou in 1905. Matisse was taken aback by Vlaminck's unrestrained use of pure, bright colors. According to Vlaminck, Matisse returned the next day saying, "I couldn't close my eyes last night! I want to see it all over again!" Matisse recalled that the best part of visiting the Chatou studio was "the comfort of knowing that two much younger men had independently reached the same point as [himself]."

At the Salon des Indépendents, Vlaminck only managed to sell one painting and used the money to pay for the birth of his third daughter. He exhibited at the 1905 Salon d'Automne, where his work was grouped with his friends in a space labeled 'Cage aux Fauves' (Cage of Wild Beasts) by Louis Vauxcelles, an art critic, who unwittingly coined the name for the movement. Vauxcelles declared that Vlaminck and Derain used their colors as though they were "charges of dynamite" and referred to them as "Incohérents." Matisse introduced Vlaminck to Ambroise Vollard, one of the most important art dealers of the early-20th century, and after seeing his work Vollard bought the contents of his studio and gave him a solo show the following year.

Vollard's support allowed Vlaminck to give up teaching and pursue a full time career as a professional artist. He and Suzanne separated following the birth of their third daughter and he married one of his students, Berthe Combe, a fashion designer. "He described her as more than a wife, but 'a friend who understands what is in my mind before I've expressed it." They had two daughters together.

In 1908 Vlaminck's style changed dramatically; his palette became darker and nearly monochromatic and the influence of Cézanne is evident. He briefly began experimenting with Cubism although he denied having any interest in the style. He related how he "was suddenly confronted with a Cubist painting at Paul Guillaume's gallery as late as 1914" and at that moment "was no longer on [his] own ground." It was as though, declared Vlaminck, "I was on the brink of an abyss." His bitterness towards Cubism developed from the belief that the style had usurped the role of Fauvism in the unfolding of modernism. He blamed Picasso, whom he "regarded as a trickster and an imposter." Despite these virulent attacks, he claimed in his book Tournant dangereux (1929) that he was directly involved with the birth of the movement during a "lively art discussion" at a small bistro. While he can be credited with the discovery of the inspirational African sculptures in Argenteuil in 1902 and selling a mask to Derain, his direct involvement in the movement was short lived.

At the beginning of the First World War, Vlaminck was mobilized but avoided combat by serving in the war effort close to Paris. Following the end of the war, he had his second solo show in 1919. A Swedish businessman purchased ten thousand Francs worth of his paintings, allowing him to retire to Eure-et Loire southwest of Paris. There, he began isolating himself from his contemporaries.

Late Years and Death

Vlaminck's late work is often criticized for being repetitious and lacking innovation. He began to move further away from the vibrant style of his early Fauvist paintings, producing monochromatic rural scenes. Despite the criticism, Vlaminck enjoyed a great deal of success during the interwar years. Several books were published about him and in 1933 he had a retrospective at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Paris. In 1937 his work was included in the Exposition des Artistes Indépendants held at the Petit Palais in connection with the Paris Exposition Universelle.

Vlaminck's success attracted the attention of the Germans during the Second World War and he was invited to join a group of French artists touring for the Third Reich. During his time spent traveling in Nazi Germany, he published Portraits avant décès, a book he authored in which he criticized modern art. He considered it "an art made of theories," asserting that, in modern art," metaphysical painting and abstraction replace sensibility" and that the art "lacks moral health." While many of the accusations he made against modern art movements such as Cubism and artists such as Picasso were written as early as 1937, the publication of the book during a time when many artists were under direct threat by the Nazis, earned him the label traitor.

In June of 1942, Vlaminck published an article in the daily journal, Comœdia, condemning Cubism and Picasso in which he described the latter as "this Catalan with the face of a monk and the eyes of an inquisitor who never speaks of art without a private smile showing on his lips." "Picasso's unforgivable sin?" demanded Vlaminck of his readers before responding on their behalf, "Cubism. It is difficult to kill what does not exist. But it is true, it is the dead who must be killed... Pablo Picasso is guilty of having forced French painting into the most fatal of impasses, into indescribable confusion. From 1900 to 1930 he led it to negativism, impotence, death. Cubism is as remote from painting as pederasty is from love." Vlaminck was arrested and interrogated following the liberation of France due to his alleged involvement with the German propaganda campaign. He was not prosecuted for his actions; however, his reputation was tarnished.

Despite Vlaminck's diminished reputation, he participated in the Fauvist Exhibition of 1947 and the Venice Biennale in 1956. Additionally, he was elected as a member of Belgium's Royal Academy in 1955 and given a major retrospective at Galerie Charpentier in 1962. Vlaminck actively painted and wrote until his death in 1958.

The Legacy of Maurice de Vlaminck

Vlaminck received a great deal of recognition during his lifetime. While he is often remembered as an artist, he was also a successful writer, publishing multiple novels, poems, screenplays, and articles. Vlaminck may be regarded as, in his words, the "wildest beast," determined to "burn down the École des Beaux-Arts" with his "cobalts and vermilions." His opposition to tradition and his resolve to experiment with new art forms made him a leader in innovation.

Although Vlaminck's late career was far less innovative, his use of color and powerful brushstrokes during the height of his Fauve years had a lasting effect on modern art, inspiring specific Expressionist movements such as Die Brucke, Blaue Reiter, and Neo-Fauvism. French poet and art critic, Guillaume Apollinaire once referred to Vlaminck as "one of the most talented painters of his generation." His simple and intensive technique," wrote Apollinaire, "allows the lines their full liberty, the volumes their full relief, and the colors their full clarity, their full beauty."

Influences and Connections

-

![André Derain]() André Derain

André Derain ![Émile Zola]() Émile Zola

Émile Zola

-

![Expressionism]() Expressionism

Expressionism -

![Die Brücke]() Die Brücke

Die Brücke -

![Der Blaue Reiter]() Der Blaue Reiter

Der Blaue Reiter ![Neo-Fauvism]() Neo-Fauvism

Neo-Fauvism

Useful Resources on Maurice de Vlaminck

- In Montmartre: Picasso, Matisse and the Birth of Modernist ArtOur Pickby Sue Roe

- Les Fauves: A sourcebookby Russell T. Clement

- Dangerous Cornerby Maurice de Vlaminck